RA TREATMENT TG

advertisement

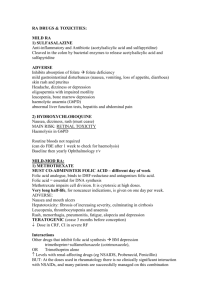

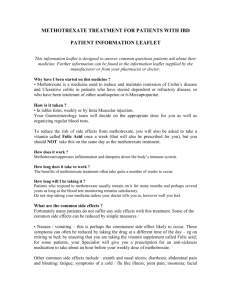

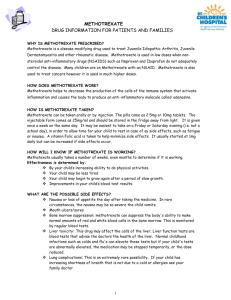

RA TREATMENT TG Background RA is a systemic inflammatory disease that, at least initially, focuses on synovial joints. The prevalence of RA is about 1%, and women are more commonly affected than men. The prognosis of treated RA has substantially improved in the last 20 years, with the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) resulting in better control of inflammation and less joint damage. These better outcomes contrast with those for untreated RA. Between 15% and 70% of the risk of developing RA may be due to genetic factors. Patients with RA express a ‘shared epitope’ in leucocyte antigens including HLADR1, HLA-DR4 and HLA-DR10, at a higher rate than in the general population, and patients doing so have more severe disease. Nonetheless, HLA typing is not used for prognostication in the routine management of patients with RA. Putative environmental factors include smoking and viral infections. RA is best characterised as a lymphocyte-mediated inflammatory disease. The stimulating antigen(s) are unknown, but pro-inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines and prostanoids, exist in the joint, resulting in cellular activation, migration and proliferation. The cytokines tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin 1 (IL-1) appear to be key factors, although others are also involved. This pro-inflammatory milieu results in joint destruction, with both erosions and cartilage loss. The aims of RA therapy have radically shifted from palliation to early induction of disease remission to prevent joint damage. The key elements of the current approach to RA are in Box 12.5. Approach to the management of RA (Box 12.5) RA should be diagnosed and treatment commenced with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) as early as possible. DMARD and other therapies should be used to induce an inflammatory remission and thus prevent joint damage. RA patients need to be regularly monitored for drug toxicity and to minimise RA comorbidities such as osteoporosis and atherosclerosis. All patients with RA should be educated about their disease, and participate actively in its management. DIAGNOSIS The key diagnostic feature in early disease is the presence of synovitis, which is manifest as soft tissue swelling or an effusion of the affected joint. Tenderness of the joint line alone is insufficient to demonstrate synovitis. Rheumatoid factor is present in about 70% of established RA patients but is detected less frequently in early disease. The presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies is more specific for RA, but a little less sensitive. Early diagnosis and management of RA results in better outcomes for patients. A number of features in early inflammatory arthritis suggest a diagnosis of RA, see Box 12.6. Features in early inflammatory arthritis suggesting a diagnosis of RA (Box 12.6) symptom duration of >6 weeks early morning stiffness of >1 hour arthritis in 3 or more regions bilateral compression tenderness of the metatarsophalangeal joints symmetry of the areas affected Rh factor positivity anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody positivity bony erosions evident on radiographs of the hands or feet, although these are uncommon in early disease PROGNOSIS Once a diagnosis of RA has been established, it is important to establish the likely prognosis of the disease to allow rational therapeutic planning. The factors listed in Box 12.7 indicate a poorer prognosis and this supports a more intensive approach to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy. Unfortunately no single prognostic factor is entirely reliable in an individual RA patient. Indicators of a poorer prognosis in patients with RA (Box 12.7) Sociodemographic factors: onset in early adulthood female elderly-onset male adverse socioeconomic circumstances smoking Clinical factors insidious onset longer duration of disease at presentation greater number of swollen joints (>20) [NB1] involvement of small joints of hands and feet extra-articular features (eg nodules) impaired physical function Laboratory features at onset presence of anti-CCP antibodies high rheumatoid factor titre [NB1] elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) [NB1] erosions on imaging certain HLA-DR types (HLA-DR1 +/- HLA-DR4 +/- HLA-DR10). HLA typing is not routinely done. NB1: The most important factors are a positive rheumatoid factor, sustained raised measures of inflammation (CRP or ESR), and a high number of swollen joints. UNDIFFERENTIATED INFLAMMATORY ARTHRITIS A consultation with a patient with recent-onset inflammatory arthritis should, optimally, lead with minimal delay to the diagnosis and a plan for the initial management. The nature of the treatment provided while waiting for investigations to be performed, or for a specialist consultation to occur, will depend on the severity of the symptoms, the age of the patient and their other medical problems. In a patient with mild to moderate symptoms but who is otherwise in good health, use: NSAID orally, see Table 1.2. The potential benefit of NSAIDs should be weighed up against their potential risks, particularly in high-risk patients. In those with severe symptoms and associated functional impairment, or in the elderly with or without renal impairment where there is greater risk of NSAIDinduced toxicity: Low-dose prednis(ol)one may be required. However, starting prednis(ol)one before specialist review may delay diagnosis. If it is considered essential for rapid symptom relief in such patients, use: prednis(ol)one 5 to 10 mg orally, daily. See Adverse effects of corticosteroids for a discussion about bone density loss associated with corticosteroid therapy. The immediate or subsequent initiation of a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) would generally be on the advice of a specialist, who would also facilitate the withdrawal of the prednis(ol)one. NSAIDs are often continued even after the initiation of a DMARD. DIAGNOSED RA A management plan for each patient should be negotiated between the patient, the specialist, the general practitioner, and other health professionals. The ultimate goal of therapy remains the prevention of joint damage and maintenance of quality of life. The ongoing management of a patient with RA involves repeated: assessment of the current inflammatory activity of the arthritis (eg early morning stiffness, joint pain, swollen joint count, ESR or CRP) assessment of the joint damage (eg physical examination or X-rays) adjustment of the DMARD and other therapy to induce and maintain an inflammatory remission in the arthritis, and then maintain therapy as necessary assessment and management of the potential complications of RA (eg atherosclerosis, osteoporosis, vasculitis) assessment of the potential toxicity of the current pharmacological therapy (including appropriate blood test monitoring) referral to other health professionals as appropriate (see Management of chronic rheumatological diseases). Recent-onset RA The choice of the initial disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) for a patient after diagnosis of recent-onset RA will be influenced by: its severity, and likely prognosis, the patient age and their other medical problems, beliefs of the patient and doctor as to how the best outcome can be achieved. A response to DMARD therapy should be apparent within 12 weeks. In mild RA, consider: 1) Hydroxychloroquine 2) Sulfasalazine For mild to moderate RA (in a patient with no contraindications) 1) Monotherapy with methotrexate may be sufficient. In very active RA (with significant functional impairment) Initiation of combination therapy: consider (all together) 1) Methotrexate 2) Hydroxychloroquine 3) Sulfasalzine) WHILE AWAITING ONSET OF EFFECT: Consider Steroid treatment, Pulse or as intra-articular therapy Once DMARD therapy is started, disease-specific outcomes (see Disease activity and outcome measurement) should be measured, and therapy adjusted to achieve remission. See Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for more details on DMARDs. Disease activity and outcome measurement The key feature of the modern management of RA is that disease activity is measured and used to adjust therapy to attain remission. Remission is defined as: symptomatic relief, plus normalisation of inflammatory markers, and the absence of joint swelling. Induction of remission should always be the goal of the treatment of RA, and can be achieved in about 50% of cases. Various measures of disease activity have been developed which may reflect inflammatory activity, joint damage or a combination of both. Decisions about the adjustment of DMARD therapy should be guided by measures that reflect inflammation. The presence of swollen joints and raised measures of inflammation such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), are probably the most reliable. The absence of these objective measures of inflammation suggest that the patient’s symptoms may be caused by joint damage, other painful processes or pain amplification. NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT Exercise Diet - controversial Education Other lifestyle changes The systemic inflammation of RA is probably the main contributor to the increased risk of developing atherosclerosis, but traditional risk factors remain important, and should be assessed and treated PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT: 1) SYMPTOMATIC TREATMENT NONSTEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS Effective therapy, High incidence of adverse drug reactions. If gastrointestinal, cardiovascular or renal risk factors are present, careful monitoring is necessary. Alternatively, paracetamol, fish oils, or low-dose glucocorticoids may allow NSAID use to be avoided. For more information about NSAIDs, see ‘Getting to know your drugs’ (Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Fish body oil Reduces symptoms and recourse to NSAIDs in RA, It also has an antiarrhythmic effect, improves blood pressure control and arterial compliance, and reduces raised triglycerides. 14 standard 1 g capsules per day or 15 mL of fish oil/day This substantially exceeds amounts that patients take as self-medication. It is easier and cheaper to take the fish oil as bottled product on juice, GLUCOCORTICOIDS Effective therapy, High incidence of adverse drug reactions. Oral glucocorticoids should be considered in patients with acute severe disease, and in those for whom other treatment strategies have failed or are contraindicated. In such patients, use: Prednis(ol)one 5 to 10 mg orally, each morning. NB (CATEGORY A in PREGNANCY) These relatively low doses of oral prednis(ol)one may be effective in patients with RA, and doses higher than 15 mg daily should be avoided if possible. If oral prednis(ol)one is commenced, DMARD therapy should be considered to facilitate dose reduction. See Adverse effects of corticosteroids for a discussion about bone density loss associated with corticosteroid therapy. Intra-articular injections of depot glucocorticoids are effective if a small number of large accessible joints are involved. 2) DISEASE MODIFYING AGENTS Initial therapy Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) reduce or eradicate synovial inflammation and thus prevent joint damage. Choice of DMARD depends on the prognosis, the patient’s age and co-morbidities, and the opinion of the specialist coordinating care. In most patients with recently diagnosed RA, methotrexate should be commenced as early as possible to control joint inflammation. The usual initial dose is: Methotrexate 5 to 10 mg orally, weekly increasing up to a maximum dose of 25 mg weekly depending on clinical response and toxicity (see Methotrexate for information on toxicity and monitoring) GIVEN WITH Folic acid 5 mg orally, once or twice weekly (preferably not on the day that the methotrexate is taken). Monotherapy While most patients have symptomatic improvement from treatment with methotrexate, or occasionally another DMARD, as monotherapy, less than 20% will reach disease remission. If remission is not achieved then the dose of methotrexate should be increased and combination therapy considered (see Combination therapy). Combination therapy In those patients with severe disease or who fail to respond to methotrexate monotherapy, other therapies such as hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine may be added. If initial combination therapy fails to control joint inflammation, methotrexate with leflunomide, cyclosporin or other drugs may be added. If joint inflammation persists, then use of the biological DMARDs is appropriate, generally in combination with methotrexate. Methotrexate, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine (‘triple therapy’) Studies in early and established RA have demonstrated that the combination of methotrexate, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine (‘triple therapy’) is more effective, and not more toxic, than methotrexate alone, or combinations of any 2 drugs. Triple therapy can be initiated after failed methotrexate monotherapy, or on diagnosis, depending on the likely patient prognosis and their co-morbidities. See Methotrexate for information on monitoring. Methotrexate and leflunomide A single study found this combination more effective than methotrexate monotherapy, but associated with an increased risk of adverse drug reactions. Of particular concern is the increased risk of leucopenia, pneumonitis and abnormal liver function. See Methotrexate for information on monitoring. Methotrexate and cyclosporin Several studies have demonstrated that this combination is more effective than either therapy alone, with adverse effects similar to that of either drug alone. Monitoring reflects that needed for cyclosporin—see Cyclosporin for details. Methotrexate and biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) Biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) should be considered for the treatment of RA if remission is not achieved with the appropriate use of DMARDs, as discussed above. All currently used bDMARDs are more effective when used in combination with methotrexate (see Biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) for more information). All practitioners should be aware of the vulnerability of patients taking biological DMARDs, or other significant immunosuppressants, to infectious diseases such as atypical pneumonia, listeriosis, and tuberculosis. Patients should be asked to report unusual symptoms, including fever or persistent cough.