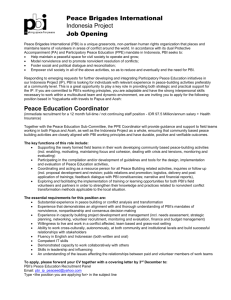

Indonesia Project/Proyek Indonesia

advertisement