Week 1: CAP

advertisement

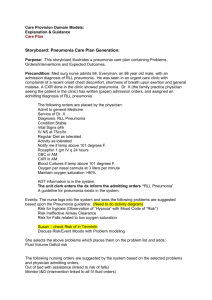

COMMUNITY ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA Lisa Sanders, MD WEEK 13 Educational Objectives: 1. Recognize the historic and physical exam findings that help discriminate between community-acquired pneumonia and other causes of acute cough 2. Identify characteristics of patients with pneumonia who can safely be treated at home 3. Name the recommended treatment strategies for the outpatient treatment of community-acquired pneumonia CASE ONE: Mrs. Plura Tick-Payne is a 65-year-old smoker with diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and depression who presents in clinic with a two-day history of cough productive of yellow sputum, chest tightness, and subjective fever. On physical exam, she is afebrile, though she tells you that she took Motrin earlier that day. Blood pressure is 150/95; heart rate is 85; respiratory rate is 20. Her O2 saturation is 95% at rest. Her lung sounds are distant, but clear, without crackles or wheezes. Questions: 1. Assess Mrs. Tick-Payne’s likelihood of having pneumonia. In the article from the Annals, the authors suggest that in any given patient presenting with acute cough, the likelihood of them having pneumonia is about 5%. In their metaanalysis, they provide likelihood ratios for how elements of history and physical exam can change that baseline probability. Most co-morbid conditions, even a history of smoking, do not significantly change the likelihood that the patient has pneumonia. (HIV may be an exception to this general statement.) Based on her history of cough and fever, and a normal exam, she has up to a 10% chance of having pneumonia. 2. How would that change if she were febrile? A fever increases her likelihood of pneumonia to just over 20%. 3. How would you rate her chances of having pneumonia if she had a fever, tachycardia and had crackles on exam? The presence of fever, tachycardia, and crackles increases her likelihood of pneumonia to almost 50%. The learning point here is that although essential in making the diagnosis, history and physical exam are somewhat insensitive and cannot give you a slam-dunk diagnosis of pneumonia. A chest X-ray is necessary for a diagnosis of pneumonia. 4. Given the original scenario, would you get a chest X-ray? Would you suggest any other tests? There is no right answer to this question, though I think many of us would feel pretty comfortable sending this patient home without the test. An elevated white count would certainly move the pre-test probability to the right, so a CBC might be useful, but wouldn’t be the standard of care. In determining the need for further testing, the physician would have to rely on his/her knowledge of the patient, including how likely it is that she would return if she deteriorates or her social support, and clinical presentation. CASE ONE CONTINUED: The patient is with her 3-year-old grandson and is unwilling to even discuss the possibility of going to get an X-ray. You send her home with instructions to call if she gets any worse. The next day you get a call from the patient who tells you that she has chills and a temperature of 101o F. You send her to the ER. Several hours later the ED attending calls and reports that she has a left lower lobe infiltrate and asks if you want her admitted to the hospital. 5. What do you tell him? This is where the Pneumonia Severity scale comes in handy. Criteria Points assigned Age > 50 in a female 55 Fever 0 (You don’t get points until T > 104 or < 95) She is at a Class II risk, with a 30-day mortality risk of less than 1%. She can be treated at home. 6. Would your decision be changed if the patient were homeless? While there is no research to answer this question, expert-based opinion suggests that psychosocial characteristics should be considered in the decision of whether or not to admit a patient. 7. What medical therapy would you choose and for how long? Two large cohort studies have found that antibiotic regimens that cover both typical and atypical organisms are associated with a lower risk of death than regimens that cover only typical bacteria. Most of the controlled trials cited in the NEJM articles relied on either new antipneumococcal fluoroquinolones or an advanced macrolide. CASE TWO: Hesa Badhoff is a 47-year-old man with a history of alcohol-related liver disease who presents to your office complaining of a productive cough and chest pain for the past several days. On exam he is febrile to 102oF, tachycardic to 128 with a blood pressure of 130/80. His oxygen saturation is 94% on room air. He appears dehydrated on physical exam though his lungs are clear. 8. How would you characterize his pretest probability of pneumonia? Pretty darned high 9. A chest X-ray shows a left lower lobe pneumonia. Does this patient need to be hospitalized? Yes. Based on the Pneumonia Severity Scale he has a score of 92 putting him in Risk Class IV, which has a 10% risk of dying within the next 30 days. NOTE: Answer to MKSAP question on resident handout is: C. Additional coverage is needed for enteric gram negative organisms for nursing home residents. References: “Testing Strategies in the Initial Management of Patients with Community Acquired Pneumonia,” J.P. Metlay MD, M.J. Fine MD, Annals of Internal Medicine, 2003; 138:109118. “Management of Community Acquired Pneumonia” E.A. Halm MD, A.S. Teirstein MD, New England Journal of Medicine, 2002; 347;25:2039-2045.