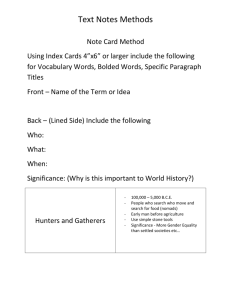

White Paper

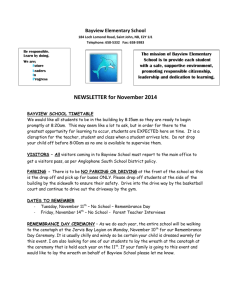

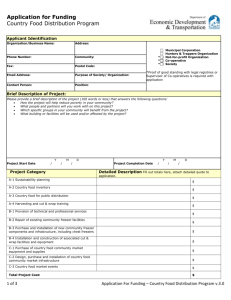

advertisement