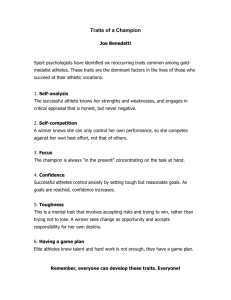

The Fundamental Goal Concept in Elite Sport

advertisement