Wildlife Biosecurity Issues

advertisement

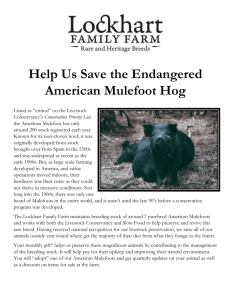

Wildlife Biosecurity Issues Where their paths cross, livestock can be exposed to disease-causing agents carried by wildlife. This may happen at a water source that livestock share with Canadian geese or a feed manger that also happens to be home to a family of mice. These are just two examples of where contact and transfer of disease can take place. You need to be aware of the risks posed by wildlife. The three main areas targeted as wildlife biosecurity concerns are feed (particularly feed storage), water sources, and the living space for the herd. Deer, birds, coyotes, pet dogs and cats, rodents, and insects can be carriers of diseases that affect other animals or humans. Deer carry a worm, Parelaphostrongylus tenuis, or P. tenuis, that can cause fatal meningitis in sheep, goats, or llamas. There are also emerging diseases that have been found in wildlife and may spread to livestock. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is being monitored for this potential. In addition, there are bacteria and other microbial pathogens that live on the farm that do not need wildlife as a host, but can easily be introduced to the herd by way of a contaminated water source. Intestinal diseases such as cryptosporidiosis, Johne’s Disease, and campylobacteriosis can all be spread in this way. Farm managers and maintenance personnel can reduce the risk of domestic animals’ exposure to these and other harmful diseases. Periodic maintenance of feed storage areas, watering systems, and animal facilities will reduce wildlife biosecurity risks. The feed, water, and facilities maintenance checklists in the next section provide guidelines which can be incorporated into maintenance routines. Regular maintenance will ensure a low risk of exposure to wildlife or other disease vectors and optimize herd health and productivity. Birds House sparrows, starlings, pigeons, and swallows commonly inhabit barns on livestock farms. Geese and wild turkeys often share ponds or pastures with livestock. Birds can spread salmonellosis and avian tuberculosis (which cross-reacts with bovine tuberculosis tests). They also can carry the organisms that cause enteric bacterial diseases, fungal diseases, Q fever and other diseases associated with mastitis and abortion, tapeworms and other parasites. Most of these diseases are also transmittable to humans. Not only can birds spread disease onto healthy farms, but they can also be an expensive nuisance. A starling will eat 50% of its body weight in grain each day. Nests that are made in barns close to the heat of a light fixture or bad wiring can be a fire hazard. To reduce the exposure of livestock to birds and their droppings, first evaluate the current presence of birds on the farm. Identify places on the farm where birds like to nest, bathe, and perch. Inspect the farm for places where there are lots of bird droppings. Observe whether birds perch on or above livestock Observe whether birds bathe in livestock water troughs. Where birds are a problem, bird detractors should be considered. Options include recordings of distress calls, whistles that make an irritating sound, as well as visual detractors, bird netting, and reflectors. Use of these methods is still no guarantee that all birds will stay off the farm. Attracting raptors like Red-tailed Hawks may help. Additional maintenance procedures should be followed to keep birds and droppings away from the herd’s feed and water. Clean out water troughs and feed bunks daily. Keep livestock away from ponds where birds congregate. Keep stored feed well-covered. Install screening to prevent birds from accessing barns. Destroy nests and eggs of nuisance birds. Thin stands of trees where starlings would roost. Discourage migrating flocks of birds from stopping at your farm. For more information on bird control visit the following websites: http://www.birddamage.com/dairy/diseases.htm http://www.agf.gov.bc.ca/resmgmt/fppa/environ/berry/berry10.htm Rodents Rodents, like birds, are found on most farms. Rats and mice live in farm buildings, feed storage areas, and woodpiles, whiling eating grain intended for the herd. They potentially spread bacteria like Salmonella and E. coli by contaminating feed with their droppings. They also may chew the insulation off of wires, causing a fire hazard. To control these risks to the herd’s health, identify and routinely bait places where rodents could potentially den in storage areas or barns. Inspect buildings and feed storage areas for evidence of rodents, such as droppings and nests. Identify their source of food and prevent their access to it. Destroy their denning places and block off any small holes to prevent them from reentering. Use traps or bait to catch rodents. Place 10 to 20 feet apart. Use tamper-resistant bait stations to protect farm pets, especially dogs, from rodent poison. Search for dead rodents and dispose of them appropriately. Do not touch them with bare hands. Prevent more rodents from coming on the farm by maintaining a clean and regularly inspected facility. For more information on rodent control visit the following websites: http://www.cpif.org/Environment/Quality%20Assurance/rodent.htm http://www.agf.gov.bc.ca/resmgmt/fppa/environ/berry/berry10.htm http://www.tulsa-health.org/env/rodent.htm. Coyotes, Dogs, and Cats Coyotes are wild canines with dog-like features. They are well-adapted to populated areas and are no strangers to farms, fields, and woods. Coyotes are less likely to attack livestock where wild game such as rabbits, squirrels, and mice are plentiful. They will also kill deer and eat carrion. How dead stock are handled may enhance a farm’s coyote population and encourage depradation of livestock. Coyotes may carry disease causing agents so should be kept out of areas where livestock are pastured or housed. For more information on coyotes, visit the following website: http://www.nationaltrappers.com/Coyote.html. Dogs may be employed on farms to help move or guard animals. Unfortunately, dogs tend to eat just about everything from Rocky Mountain or prairie oysters and afterbirth to horse manure. Unless dogs are strictly kept out of animal feed and housing areas, they may spread any of a number of disease-causing agents that can be spread through fecal-oral contamination. Of particular concern is data suggesting that dogs play a role in completing the life cycle of the protozoan parasite Neospora. Neospora causes abortion in cattle. Clearly dogs should not be able to access pastures during calving, lambing, or kidding season or maternity areas of barns. Cats may be part of a farm’s rodent control program. Like dogs, they can spread a number of disease-causing agents and may carry Neospora as well. It is best to prevent cats from living in hay mows or other areas where feedstuffs are accessible. Farm cats and dogs should be routinely vaccinated against rabies. Mosquitoes Mosquitoes can transmit diseases to you and your animals. These annoying, biting insects can carry diseases such as West Nile and other encephalitis viruses that can affect humans and horses and can carry heartworm of dogs. One of the best ways to minimize the risk of these diseases on your farm is to control the number of mosquitoes. Destroying their habitats and breeding grounds will reduce their numbers. Most mosquitoes lay their eggs on the surface of shallow water. Eggs take about 48 hours to hatch, and then the larvae (plural of larva, the immature stage of the mosquito) live in the water for about a day, eating organic material and breathing through a tube that reaches the surface. The larvae then molt into pupae (plural for pupa, similar to the cocoon stage of butterflies) where they develop for about two days, still in the shallow water. Finally, the adult emerges and leaves the water. Adult females bite a host animal to get a blood meal before breeding. The saliva that transmits diseases during a bite also causes swelling and itchy irritation. Males, on the other hand, feed on nectar and do not bite. A figure depicting the life cycle of the mosquito can be found at http://www.mosquito.org/mosquito.html. In Vermont, the primary type of mosquito is Culex pipiens, the common house mosquito. There are simple measures that can be taken to reduce their numbers. Prevent standing water as much as possible. Clean out gutters, birdbaths, and troughs regularly. If you have a pond, stock it with fish that eat mosquitoes like goldfish and mosquito fish (Gambusia). Also, damselflies and dragonflies eat mosquitoes. Make your pond with steep sides to minimize shallow water and allow fish to get to the edge to eat the larvae. For more information on mosquito control visit the following websites: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/index.htm http://www.mosquito.org/mosquito.html. Deer Deer can also introduce disease onto a farm. Deer can carry Bovine Tuberculosis, Johne’s Disease, and Chronic Wasting Disease. Sharing of pastures and shared water sources between deer and livestock should be avoided. To evaluate your farm and decrease the risk of your livestock contracting diseases from deer, do the following. Look for droppings, deer beds, and signs of deer around the perimeter of the farm and pastures. Evaluate the water sources on the farm to ensure that deer cannot contaminate the drinking water of the herd (brooks, streams, etc., that pass through grazing pastures). Prevent the herd from drinking out of these types of water sources. Secure fences along the perimeter of pastures. Wind socks may be used on fence posts to deter deer from coming close to the fence where transfer of disease or bacteria would occur. For more information on deer control, visit the following website: http://www.ext.colostate.edu/ptlk/2301.html. Photo: Ken Hammond, USDA Photography Center, used with permission.