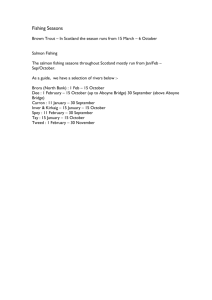

Open - The Scottish Government

advertisement