Paradigm Shifts in Approaches to Spiritual Practice in Recent Times

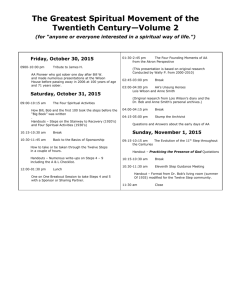

advertisement

Does Spiritual Practice Require Renunciation? Frank Vilaasa Much of what we know and practice in spiritual life has come to us through either the Vedic/Upanishad tradition of India, or through Buddhism (Tibetan, Zen, Theravada) The teachings and practices of these two streams vary considerably, but one of the things they have in common is the idea of renunciation (avoiding worldly pleasures). Traditionally, there has been a common belief that in order to advance spiritually, one must renounce the world. Yogis became ascetics and sadhus, wondering around naked and homeless, begging for their food. Buddhist monks left the world to join a monastery and wear saffron robes. Both yogis and monks practiced celibacy. Work and family life were not for them. When this tradition was first introduced, many centuries ago, worldly life was physically much more demanding than it is now. People worked in the fields all day, there were none of the modern machines and entertainments that make our present day lives easier and more enjoyable. No cars, TV, washing machines, air-con, iPads etc. Worldly life was full of hardship and toil. Even marriage brought more dependant mouths to feed. For anyone who had some spiritual leanings, renouncing this ancient worldly life was perhaps not such a big issue. In fact, it probably provided a relief from the burdens of work and family responsibility. Nowadays, with all the benefits of technology, worldly life has become more interesting and enjoyable. We can now earn more than we need for survival. Many people have extra cash to enjoy themselves - with travel, entertainment, exotic foods, music and other pleasures. Even if one has spiritual longings, the traditional teachings of renunciation are far less appealing now than they may have been two thousand years ago. For this reason, I believe it is necessary to review this aspect of traditional teachings, and examine whether it is still relevant today. Is it really an essential part of spiritual practice, or just an outdated convention that was more suited to the social norms of the past? In India, especially, the practice of asceticism has been taken to extremes. Yogis will deliberately push themselves into situations of maximum discomfort – fasting, extreme heat and cold, prolonged unnatural poses – all in an attempt to overcome the body’s desire for comfort and pleasure. The body, which represents the world for each individual, is seen as an enemy, with distracting and destructive desires which must be overcome before one can advance in spiritual life. In Buddhism, with its emphasis on the ‘middle way’, there were none of these extremes. Yet monks mostly lived in monasteries, which were exclusively male, they practiced celibacy and endeavored to overcome all worldly desires and attachments. When a young man first enters monastic life, his head is shaved, to symbolize that he is renouncing all worldly attachments. The question I want to explore here is – is renunciation necessary, or even helpful, for spiritual practice nowadays? It is true that the human mind has innate tendencies to desiring sensory pleasure and avoiding pain and discomfort. This tendency is one of the main factors that keep us trapped and enslaved in samsaric (worldly) existence. In order to advance spiritually, we must free ourselves from these mental tendencies. The question is – what is the most effective way of doing this? Is it to renounce the world and fight with the mind and its attachment to bodily pleasures? Or is there a more effective way? Do we have to conquer and subdue the mind and body, or can we transcend them without having to struggle excessively? In struggling with the desire for pleasure, there are two possible outcomes – we either sublimate the desire, or we suppress it. If we manage to sublimate the desire, it becomes transformed into a higher state, and we can eventually transcend it. In this case our efforts have been effective. If, however, instead of sublimating, we suppress the desire, then our internal energies become blocked, and no transcendence occurs. Our efforts have actually made things worse. My understanding is that unless the person undergoing these practices is already an advanced soul, who can bring a subtle and sharp discriminating awareness to the practice, then in all likelihood the outcome will be one of suppression rather than sublimation. The main reason for this is that, in most cases, the practice is approached with a great desire for spiritual advancement – i.e. in trying to overcome desire, a new desire has entered through the back door. So, rather than freeing ourselves from desire, we end up pushing our physical desires into the unconscious – where they continue to fester – and at the same time we become further enslaved to a whole new set of spiritual desires. The alternative to this approach is not to struggle with physical desire at all. Instead, we just live a normal worldly life without renouncing or avoiding anything. By being in the world, we can learn to transcend it. How can this happen? By adding one thing to our daily activities and thought processes – a sense of awareness and curiosity about our own mind. Note that we are not trying to achieve anything. We are not adding in any extra spiritual desires. We are just patiently taking the time to get to know our own minds – as intimately and as honestly as possible. As we do this, we will eventually recognize how enslaved we are to the mind’s mechanisms of desire for pleasure and avoidance of pain. We see that we are not much different from one of Pavlov’s salivating dogs – completely at the mercy of the body’s instincts and the mind’s desires and fears. And furthermore, our attachment to these pleasures is like an addiction that we seem unable to break. It is only after seeing the kind of mental prison we are in that the longing for freedom starts to arise in us. If we don’t recognize our prison for what it is, if we think that the perpetual experiencing of sensory pleasures is just a really fun way of living life, the longing for liberation will never be awakened in us. By observing the mind, we start to see what a mechanism it is, and how enslaved we are to this mechanism. Then a new awareness arises in us – the awareness that I am not free. I am a slave to my own mind. And a great longing arises in the heart and soul to be free from this mind. To transcend the mind and merge with the clear blue sky that lies beyond. To go beyond oneself. To live each moment in the bliss of total freedom. This longing of the soul is not another mental desire. It is the natural yearning of the soul to experience moksha or liberation. This longing is essential for us to complete our spiritual journey. We can awaken it just by living a normal worldly life, and watching the mind as we do so. Nothing further is required. This kind of ‘secular’ spirituality is becoming more prevalent now in Western countries where some of the ancient Eastern teachings and practices have taken root. Rather than setting Samsara and Nirvana in opposition to each other, and having to choose one or the other, a new integration of both is emerging. People are discovering that Samsara and Nirvana can co-exist in harmony, that one doesn’t have to renounce one in order to attain to the other. One can enjoy both worldly life and spiritual development. This integration includes such things as intimate relationships, work and career, family, health and healing, and developing a more complete understanding of the mind through modern psychology and psychotherapy. In other words, learning to find joy in both worldly life and in spiritual attainment. It includes developing a friendly and accepting attitude towards the body and its instincts. It may also include tantric practices to transform the body’s basic instinctual energies of sexuality and anger/fear into the more refined energies of love and consciousness. This is the path of self acceptance and integration, rather than of renunciation. It represents a paradigm shift in the way that spirituality is being approached.