Ethics and the Vision of Value, presents a position in normative

advertisement

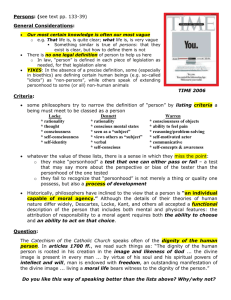

Ethics and the Vision of Value Timothy Chappell If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, infinite. William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Plate 14 1 Ethics and the Vision of Value Contents Preface Part One: Metaethics Chapter 1: Moral perception Chapter 2: Expressivism, error theory, and relativism Chapter 3: Emotion, moral perception, and desire Chapter 4: Normative and non-normative properties Part Two: Normative Ethics Chapter 5: The Good-to-Right Function: Some Unsuccessful Accounts Chapter 6: Practical Rationality for Value-Pluralists Chapter 7: Goods and Persons Chapter 8: The action-omission and double-effect distinctions Bibliography 2 Preface This book begins with the idea of vision in moral theory. Part One is about metaethics: it develops the thesis that one of the ways in which we can know about moral properties is by means of something that can reasonably be called perception. In chapter 1, the guiding idea is that perception is pattern-recognition. When we see or hear or smell, we are picking up a pattern. When we read a sentence in a book, we are picking up a pattern. When we see that murder or treachery is bad and that friendship or kindness is good, that too is pattern-recognition—and this moral pattern that we pick up is just as real as the other patterns that we pick up in other forms of perception. Developing this metaethical view involves me in showing how it does better than important contemporary rivals such as expressivism. Familiarly, expressivism makes moral utterance at bottom a matter of expressing our attitudes, and only a matter of asserting truths insofar as a quasi-realist discourse of truth-apt assertions can be constructed on the basis of such expressive utterances. Such a construction cannot, or so I argue in chapter 2, get anywhere near far enough. One rough way of putting the basic reason why not is this: attitudes require owners in a way that truths do not. The attitude, say, that slavery is wrong is always and essentially someone’s attitude, whereas the truth that slavery is wrong is not essentially anyone’s: it is “public property” in a way that no attitude can ever be. To put it another way, expressivism is a relativism. I add (in chapter 3) that expressivism also presupposes an untenable view of the emotions, as unstructured, non-cognitive reactions to the facts; the perceptual version of moral realism generates a more plausible analysis of the emotions, and of some other important phenomena too, such as desire. If normative properties are patterns in reality like other properties, and if perception is pattern-recognition, then recognising normative properties can be just as much a matter of perception as, say, reading is, or understanding spoken language. Such a picture of normative properties pushes us naturally towards a key question about them, addressed in chapter 4: how to characterise the difference between normative properties and non-normative properties. I argue against some of the bestknown ways of attempting to do this (the “is-ought gap” distinction; the descriptive/ prescriptive distinction; the natural/ non-natural distinction), and propose that in fact there are two gaps in the relevant area: between mere description and evaluation, and between evaluation and prescription. I begin Part Two of the book with the key normative-ethical question of what we ought to do about these normative moral properties and their instances: as we might also say, how we ought to respond to them, or what reasons they give us. After criticising consequentialist accounts of response to the goods in chapter 5, I develop a non-consequentialist picture in chapter 6. The basic thought is that the goods are irreducibly different, and that this puts limits on the ways we can trade off one good for another. Where we acknowledge a plurality of goods as different but of equally fundamental importance, we cannot see just any sacrifice of one as legitimated by the demands of the other, and vice versa. Each good is therefore “ring-fenced”, protected, against the demands of the other goods. Certain ways of treating it while pursuing the other goods are off limits, because to treat it those ways would be to cease to treat it as a good at all; as I shall say, it would be to violate that good. 3 The questions which the goods are, and which of them are the goods of fundamental importance, are the central questions of chapter 7. My answer focuses on persons. The notion of a person is notoriously problematic, and exhibits some slide between a tight and exclusive notion of personhood such as that found, say, in Frankfurt 1988: 14’s contention that nothing can be a person unless it has secondorder volitions, and a looser and more inclusive notion of persons in something like the legal sense of that term—as human (or similar) animals. I argue that this looseness in the term “person” is no accident, and that it is crucial to see that personhood in the exclusive sense is always an achievement of persons in the inclusive sense—an achievement that is only made possible by our treating one another as persons in this tight sense, even when we fail to display the marks of tight-sense personhood. Tightsense personhood is an ideal to which members of the moral community aspire. That means that it cannot be used to set the boundary of the moral community; it is the loose sense of personhood that does that. So persons are the most important goods, and this means persons in the inclusive sense—human and similar animals. A further question is what counts as violation of the goods that persons are. I argue that deliberate and direct killing of persons is a central form of violation, a conclusion that has important implications for our society’s debates about abortion, euthanasia, capital punishment, and war. This distinction between “deliberate and direct” and other killing needs to be spelled out. Spelling it out brings us to the classic distinctions between actions and omissions, and between the foreseen-and-intended and the merely foreseen— distinctions that in any case have a natural place in a pluralist normative ethics. In chapter 8 I develop a strategy for defending the reality and moral significance of both distinctions. This strategy appeals to a particular view of causation, and to a distinction between local and global conceptions that has already been proposed in chapter 5. The local/ global distinction turns out to play a crucial role, also, in dealing with some technical problem-cases for the action/ omission and double-effect distinctions. My views on all these issues have been much refined, though no doubt not refined enough, by criticism and encouragement from other philosophers. Among many others, I am particularly grateful for their help and comments to Liz Ashford, Alex Barber, Peter Baumann, Chris Belshaw, Michael Brady, Tal Brewer, Sarah Broadie, Vivienne Brown, Alan Carter, John Cottingham, Christopher Coope, Rowan Cruft, Garrett Cullity, Ashley Cummins, Cora Diamond, Sabine Doering, Jamie Dow, Antony Duff, Keith Frankish, Peter Goldie, John Haldane, Katherine Hawley, Brad Hooker, Kent Hurtig, Rosalind Hursthouse, Simon Kirchin, Dudley Knowles, Jimmy Lenman, Stephen Makin, Derek Matravers, Alan Millar, Fred Miller, Adam Morton, Tim Mulgan, David Oderberg, Eric Olson, Onora O’Neill, Tim O’Hagan, Jon Pike, Carolyn Price, Duncan Pritchard, Michael Ridge, Paul Russell, Dory Scaltsas, John Skorupski, Christine Swanton, Jussi Suikkanen, Alan Thomas, Chris Tollefsen, Bernard Williams, Nick Zangwill, Linda Zagzebski. I have been very privileged, too, in the level of institutional and financial support that I have received while writing this book, not only from my own 4 institution, that unique phenomenon The Open University, but also from the Institute for Advanced Studies at the University of Edinburgh, and the Centre for Ethics, Philosophy and Public Affairs at the University of St Andrews, who were kind enough to offer me Visiting Fellowships during my year’s sabbatical in 2005-6. Thanks are due also to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for their funding of that sabbatical. Finally, the love and support of my family represents a quite different sort of debt: one that I am happy to acknowledge as unrepayable, and to continue incurring indefinitely. Timothy Chappell The Open University Walton Hall Milton Keynes, England February 2007 5