Subdivisions of temperature concepts

advertisement

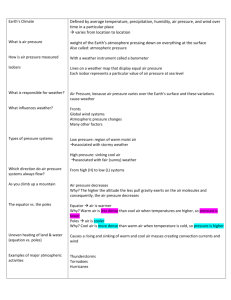

Mika SHINDO, Kyoto University (Japan): contact e-mail address.: mikashindo@gmail.com Subdivisions of Temperature Concepts This paper deals with subdivisions of temperature concepts by examining the semantic extensions of temperature adjectives to the abstract domains. My first corpus-based approach examined whether the four English temperature adjectives, hot, warm, cool, and cold are all mapped in the same manner to the domain of emotional feelings etymologically revealed by Sweetser (1990). We collected all temperature adjective-noun pairs from the British National Corpus by using Robust Accurate Statistical Parsing (RASP, Briscoe and Carroll 2002), and then classified these pairs by using a lexical database WordNet 2.0. (Shindo 2004, 2008, Shindo et al. 2005) Looking at the result of this examination, we notice a startling contrast between the two pairs of hot/cold and warm/cool. That is, when expressing emotional meanings, hot/cold and warm/cool co-occur with different kinds of nouns, as shown below: hot/cold + [entity (e.g. blood, sweat, shoulder)] emotional meanings warm/cool + [communicative relation (e.g. welcome, reception, response)] emotional meanings This difference in the temperature domain is attributable to the original, typical meanings of hot/cold and warm/cool. That is, hot/cold typically represents the temperature of an object felt by a part of the body, while warm/cool typically stands for the physiological temperature felt by the whole body. Even when used for extended meanings showing emotions, hot/cold describes a person’s emotions by expressing the temperature level of a bodily fluid, such as blood or sweat. On the other hand, warm/cool illustrates a person’s emotions by considering social communication as the air surrounding us and describing the air’s temperature as warm or cool. This result may indicate the fact that the temperature concept evokes two models based on typical experiences: heated fluids and air conditions. This existence of two subdivisions of temperature is verified by two perspectives. One is the metaphorical perspective. (Lakoff 1987, Kövecses 1990, Ungerer and Schmid 1996, Grady 1997, Johnson 1997, Lakoff and Johnson 1999) Kövecses clearly discusses how the two metaphors, Emotions Are Heat and Affection Is Warmth, use distinct temperature domains as their sources (Kövecses 2000: 38-39). The other is the typological perspective. English does not normally distinguish these two typical experiences of temperature, while some other languages express them with different words. For example, Japanese distinguishes between the two meanings of temperature words: the words expressing object temperatures felt typically by some part of the human body (tsumetai, nurui, atatakai1, atsui1), and the words expressing physiological temperatures felt typically by the whole body (samui, suzushii, atatakai2, atsui2). (Kunihiro 1965, Kageyama 1980). Korean also has the two types of sensation: direct perception by touching in a tactile way, and indirect perception via the air in a non-tactile way. deobda and ddeuggeobda refer to non-tactile and tactile ‘hot,’ respectively, whereas chubba and chaggeibda would refer to non-tactile and tactile ‘cold,’ respectively. Russian also distinguishes these two types of sensation for the highest temperature (Koptjevskaja-Tamm and Rakhilina 2006). These results of metaphorical and typological studies clearly reveal our ways of conceptualizing those perceptual domains are firmly based on our bodily experiences. (496 words) References Briscoe, Ted, and John Carroll. 2002. “Robust Accurate Statistical Annotation of General Text.” Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2002), 1499-1504. Grady, Joe. 1997. Foundations of Meaning: Primary Metaphors and Primary Scenes. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. Johnson, Christopher. 1997. “Metaphor vs. Conflation in the Acquisition of Polysemy: The Case of See.” In Masako K. Hiraga, Christopher Sinha, and Sherman Wilcox (eds.), Cultural, Typological and Psychological Issues in Cognitive Linguistics (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 152), 155-169. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Kageyama, Taro. 1980. Nichiei Hikaku Goi no Kouzou. Tokyo: Shohakusha. Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria, and Ekaterina V. Rakhilina. 2006. “‘Some Like It Hot’: On Semantics of Temperature Adjectives in Russian and Swedish.” In Torsten Leuschner and Giannoula Giannoulopoulou (eds.) STUF (Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung): A Special Issue on Lexicon in a Typological and Contrastive Perspective, 59 (3), 253-269. Kӧvecses, Zoltӑn. 1990. Emotion Concepts. New York: Springer-Verlag. Kӧvecses, Zoltӑn. 2000. Metaphor and Emotion: Language, Culture, and Body in Human Feeling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kunihiro, Tetsuya. 1965. “Nichiei Ondo Keiyoshi no Igiso no Kouzou to Taikei.” Kokugogaku 60, 199-213. Lakoff, George. 1987. Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh. New York: Basic Books. Shindo, Mika. 2004. “A Corpus-Based Study of Semantic Extensions of Sensory Adjectives from Synchronic and Diachronic Perspectives.” Paper Presented at the Conference of Conceptual Structure, Discourse and Language (CSDL-2004). Edmonton: University of Alberta. Shindo, Mika. 2008. (In press) Semantic Extension, Subjectification, and Verbalization. Lanham/New York: University Press of America. Shindo, Mika, Kiyotaka Uchimoto, and Hitoshi Isahara. 2005. “Semantic Extensions from Sensory Domains: A Reanalysis of Source Domains Using Natural Language Processing Skills.” Proceedings of the Third Interdisciplinary Workshop on Corpus-Based Approaches to Figurative Language—held in conjunction with Corpus Linguistics 2005, 64-71. Birmingham: University of Birmingham. Sweetser, Eve E. 1990. From Etymology to Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ungerer, Friedrich, and Hans-Jorg Schmid. 1996. An Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics. New York: Longman.