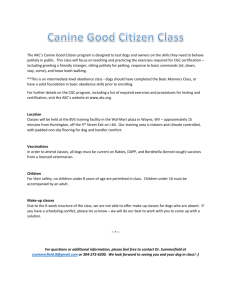

Dog Health and Reproduction

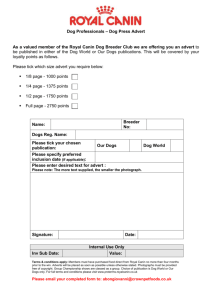

advertisement

Dog Health and Reproduction NUTRITION Dogs are classified as carnivores but they can eat some plant products. A dog's nutritional health depends on receiving the correct amounts and proportions of nutrients from the six required groups: water, protein, fat, carbohydrates, minerals and vitamins. With the exception of water, commercial pet foods identified as 100 percent complete and balanced contain all of these required nutrients. These nutrients are also present in the proper proportions. Commercial dog foods are available in three different forms: dry, canned and soft-moist. These forms differ mainly in the amount of water they contain. Dry food contains the least water and canned contains more water than the soft-moist forms. Labels of all pet foods must list the ingredients present and the guaranteed analysis. The ingredients must be listed on the label in order of weight. This is one of the best ways to determine the quality of the food. The guaranteed analysis indicates the amounts (levels) of protein, fat, carbohydrates, fiber and other nutrients in the dog food. Dog food labels also provide general feeding guidelines. Standards: Dog foods labeled as "complete and balanced" must meet standards established by the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) either by meeting a nutrient profile or by passing a feeding trial. In 1995, the AAFCO's Canine Nutrition Expert Subcommittee revised its dog food nutrient profiles. Profiles are expressed at two levels: one for growth and reproduction and one for adult maintenance. Maximum levels of intake of some nutrients have been established for the first time because of concern that overnutrition, rather than undernutrition, is a bigger problem with many pet foods today. The standards include recommendations on protein, fat, fat soluble vitamins, water soluble vitamins and mineral content of foods. The levels of nutrients in the tables are expressed on a "dry matter" (DM) basis. On most pet food labels, the levels listed in the guaranteed analysis are expressed on an "as fed" basis. To convert "as fed" to "dry matter," a simple conversion is necessary. If a dry food has 10 percent moisture it has 90 percent dry matter. For example, a label indicates that the protein level is 20 percent. Dividing the 20 percent protein by the 90 percent dry matter yields 22 percent protein on a dry matter basis. All of the nutrients of dog food can be compared this way. Table 1 provides a summary of the AAFCO dog food nutrient profiles. The complete profiles provide levels for the specific amino acids (protein), and specific minerals and vitamins. Table 1. AAFCO Recommended Nutrient Levels in Dog Food Nutrient Growth and Reproduction (minimum) Protein Fat Calcium Phosphorus 22% Maintenance (minimum) 18% 8% 5% 1% 0.6% 0.8% Metabolizable Energy 0.5% 3.5 - 3.6 Kcal/g 3.5 - 3.6 Kcal/g The basis for the nutrition of dogs comes from the 1985 publication of the National Research Council (NRC), "Nutrient Requirements of Dogs" (A report of the Committee on Animal Nutrition. Washington. D.C.: National Academies Press). Protein: Dietary proteins that are digested in the stomach and small intestine are broken down to form free amino acids which are then absorbed into the bloodstream. Amino acids are distributed to all cells of the body where they are used to build body proteins. Proteins are derived from both animal and plant sources. Proteins are selected to balance out deficiencies and/or excesses of amino acids when selecting ingredients for use in dog food diets. Plant protein sources are completely satisfactory for all phases of a dog's life if they are properly processed and when balanced ratios of amino acids are present. Digestibility and amino acid levels determine protein quality. Fat: A true requirement for fat is not established, but the minimum level of fat in the diet was based on recognition of fat as a source of essential fatty acids, as a carrier of fat-soluble vitamins, to enhance palatability, and to supply an adequate energy (caloric) density. Fats are concentrated forms of energy. Compared to proteins and carbohydrates, fats contain approximately two and a half times the amount of energy per pound. Fats from both animal and vegetable sources can be used with almost equal efficiency for the production of energy. Dogs require linoleic acid. It is an essential fatty acid that cannot be made in the body, so linoleic acid must be supplied in very small amounts in the diet. Minerals: Nutritional issues related to minerals include the amount of each in the diet, proper balance of all minerals, and the availability of minerals in the animal's food. Minerals are usually grouped into macro and micro categories. Calcium and phosphorus are two very important macro minerals. Vitamins: Vitamins are required in the smallest amounts. And unlike minerals, vitamins are complex substances. Vitamins are classified as either fat-soluble (vitamins A, D, E and K) or water-soluble (B-vitamins and vitamin C). Fat-soluble vitamins depend on the presence of dietary fat and normal fat absorption for their uptake and utilization in the body. Water-soluble vitamins simply depend upon the presence of water for absorption. Balanced amounts of vitamins must be provided in complete diets. Energy: Although energy is not a nutrient, dogs and other animals have a requirement for energy that must be met by consuming dietary carbohydrates, protein and fats. Energy is a prime regulator of food consumption in most species. Energy in the form of calories (metabolizable energy in Kcal per gram or per kilogram) provides the driving force in metabolic reactions and allows for the use of all other nutrients. It also provides heat to maintain normal body temperature. Excess energy is converted to fat and stored in adipose tissues. Carbohydrates: Carbohydrates are sugars, starches and dietary fiber. Simple sugars are the smallest sugar molecules and are easily digested and absorbed. By contrast, complex carbohydrates, or starches, are combinations of simple sugars forming long chains which require more digestion before they can be absorbed into the bloodstream. The primary function of carbohydrates is to provide energy. Dietary fiber is carbohydrates which are not completely digestible. Carbohydrates are supplied in the diet by cereal grains as well as by simple sugars such as glucose, sucrose (table sugar) and lactose (milk sugar). When dogs consume diets containing more carbohydrates than are needed, excess carbohydrate energy is stored in the form of glycogen in the liver and muscles and is converted to fat and stored in adipose tissues. Carbohydrates may make up 40 to 55 percent of dry diets. A large portion of the carbohydrates in pet foods is derived from cereal grains. Cereal grains are usually processed by grinding, flaking or cooking to improve palatability and digestibility. Fiber: Fiber is the general term used to describe complex carbohydrates which are not digested by enzymes in the small intestine of dogs. Dietary fiber has numerous effects within the gastrointestinal tract. In general, fiber has a normalizing effect on the rate of passage of food through the intestine, slowing the rate in animals with diarrhea and increasing it in constipation. Dietary fiber also slows or decreases digestion and absorption of nutrients, including fat, vitamins, and minerals. As a protective mechanism, fiber can bind to some toxins and prevent their absorption into the bloodstream. Excessive dietary fiber is associated with adverse effects such as the production of loose stools, gas (flatulence), increased stool volume and frequency, and decreased dietary caloric density. FEEDING Feeding instructions or guidelines are included on most every bag and most cans of pet foods. These guidelines give the recommended amount to be fed based on growth level and weight. These are very rough guidelines and every animal has a different level of activity, metabolism and ambient environmental temperature. Also, breed, age and other environmental stresses all impact daily requirements. Common sense indicates that if a dog is thin or hungry, you should feed it more often and in greater quantity. If the dog is fat (obese) it should be fed less. Growth and Reproduction: A dog's protein requirement depends upon the life stage and activity of the dog. Generally, pups and pregnant and nursing females need more dietary protein than do adult dogs. Energy (caloric) requirements are also high during growth phases. The protein needs of a pup can be met by a high quality protein providing 20 to 25 percent of dietary calories. A growing pup requires as much as two to four times more energy per pound of body weight, relative to an adult dog. As the puppy approaches adulthood, caloric requirements for maintenance are reduced. For reproducing females, caloric requirements at the end of gestation and during early lactation can be two to four times greater than that of adult maintenance requirements. Breed Differences: Large, fast-growing dog breeds require less food per pound of body weight than small breeds. To relate energy needs to body size, energy standards for dogs are usually established by body weight. Individual animals can very greatly from these standards. Environment and Activity: Dogs housed outdoors and exposed to extreme weather (both hot and cold temperatures) have changes in their caloric requirements. During hot weather, energy needs decrease, and less food may be required. During cold weather energy needs increase to maintain body temperature and more food may be required. During seasons of conditioning and hard work, individual dogs' energy requirements will be increased above that of maintenance. Hard working dogs include hunting dogs during the hunting season, racing dogs, sheep herding dogs or any animal regularly running long distances. When the animal is not training or working, it does not have elevated caloric requirements and a maintenance-type food may be fed. REPRODUCTION A female dog is called a bitch while a male dog is called a stud. Their young are referred to as puppies, and giving birth is called whelping. Female dogs are nonseasonal, spontaneous ovulators, with one to two estrous cycles per year. Spontaneous ovulation means that the females ovulate or release eggs whether or not they are mated. The estrous cycle length ranges from 4 to 12 months. Puberty occurs at 5 to 18 months, but usually around 6 months of age. As a female comes into heat (estrus) the vulva swells and she attracts males but will not let them mate. During actual heat (estrus) the female permits the male to mate and she holds her tail to the side. The vulva remains enlarged. If the female is to be bred, breeding should be scheduled for a total of three matings over five days, every other day, beginning with the day she is first willing to accept the male. If this is not possible, then the female can be bred on days two and four of estrus. Or, if she can only breed once, she should be bred on day two or three of estrus. Reproductive performance of a bitch is best prior to 4 years of age. Fertility and productivity (fecundity) decreases significantly after 8 years of age. Pregnancy: Pregnancy can be confirmed by palpation at day 20 to 35 or by ultrasound at day 17 and up. Physical changes that occur later can also be used to confirm pregnancy. Mammary glands start enlarging around day 40 and body weight increases during the last half of gestation. Gestation lasts 56 to 69 days and litter size can be 2 to 15, depending on the breed. Whelping: A nesting box should be provided one to two weeks before the due date in a quiet, secluded area. During the first stage of whelping, the bitch will exhibit restlessness, panting and nesting. Parturition, the birth of pups, is the second stage. Parturition can last 2 to 18 hours depending on the number of pups, but no more than two hours should pass between pups. Stage three is the expulsion of the placenta. This usually occurs immediately after each pup but no more than 12 hours after the last pup. Neutering is the best way to prevent pregnancy. Early neutering at less than 12 weeks of age is safe and effective. A drug such as Ovaban can be used to postpone the onset of estrus. Newborn Pups: Colostrum, the mother's first milk, is very important to the newborn pups. They must nurse in the first 12 to 24 hours to ensure passive transfer of antibodies for protection from disease. The pup's eyes open around 10 days of age. Pups can be weaned at six weeks of age, but they begin eating solid food around three weeks of age. Socialization to humans is critical at an early age, about 3 to 12 weeks of age. COMMON DISEASES Dogs are affected by a variety of infectious and noninfectious diseases. Many of the infectious diseases are preventable with a vaccination. Rather than describe all of the diseases that can be prevented by a vaccination, the name, pathogen and vaccination recommendations are given in Table 2. Table 2. Common Infectious Diseases of Dogs Preventable with a Vaccination Name Distemper Pathogen Vaccination Schedule Airborne virus Yearly after initial series of 3 Canine hepatitis Virus in urine Yearly after initial series of 3 Parvovirus Leptospirosis Rabies Virus in feces Yearly after initial series of 3 Bacteria Yearly after initial series of 2 Virus in saliva * See note below. Coronavirus Virus in feces Yearly after initial series of 3 Parainfluenza Virus Yearly after initial series of 3 Bordetellosis Bacteria Yearly after initial series of 3 *Note about rabies vaccination: Dogs receive one vaccination at 6 months of age and then yearly thereafter in some areas of the U.S. If the dog receives the first vaccination for rabies at 6 months of age, then a yearly vaccination is required. If the dog receives the first vaccination for rabies at 18 months of age, then a vaccination is required every three years thereafter. All dogs should be vaccinated for distemper, rabies, canine adenovirus-2 (hepatitis and respiratory disease), and canine parvovirus-2. Based on the recommendations of a veterinarian, these vaccinations should also be given: canine parainfluenza and bordetellosis (Bordetella bronchiseptica). Both are causes of "kennel cough," coronavirus and leptospirosis. A veterinarian should be consulted as to the type of vaccine and schedule based on the type. Other Infectious Diseases: Other infectious diseases of dogs include canine brucellosis, canine herpesvirus, pseudorabies, salmonellosis, camylobacteriosis and mycobacteria. Canine brucellosis is caused by a bacteria (Brucellosis canis). The disease has worldwide distribution. Like brucellosis in other animals, it causes abortion in females. In the males, the testicles may swell or shrink. Brucellosis is spread during mating. Infected animals should be neutered and not allowed to breed. Treatment with antibiotics may be successful. Canine herpesvirus is a viral disease of pups less than six weeks old. It is spread by contact with the virus in saliva, feces and urine and discharges from the nose, mouth and vagina. Adult dogs fail to show signs of the disease but can spread the disease. Infected females infect pups during the passage through the birth canal. Infected pups have a change in the color of their feces, fail to nurse, constantly cry, and show signs of difficult breathing and abdominal pain. Death occurs shortly after the signs. No vaccines are available. Pseudorabies is caused by a virus and occurs in areas where pseudorabies is found in swine herds. Signs of the disease include intense scratching, self-mutilation, convulsions, paralysis and coma. Death follows in 24 to 72 hours. No effective treatment exists. Salmonellosis and camylobacteriosis are bacterial infections of dogs that cause fever, diarrhea and vomiting. Antibiotics can successfully treat these diseases. Sanitation is the key to prevention and also prevents the spread to humans. Mycobacterial organisms causes lesions that fail to heal and continually drain. Antibiotics are not effective for treatment and the preferred method of treatment is surgical removal. Fungal Diseases: Ringworm in dogs can be caused by one of three fungal organisms: Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum, or Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Signs of ringworm include broken hairs around the face, ears or feet; red, scaly skin; and itching. After the affected area is clipped, baths, dips, creams or lotions containing antifungal agents should be applied. Some oral medications are also available. Blastomycosis, histoplasmosis and coccidioidomycosis are all systemic (one or all of the body systems) fungal diseases of dogs. Treatments for these diseases require months of expensive therapy. Internal Parasites: A variety of internal parasites can infect dogs, including: Roundworms or ascarids (Toxocara canis) Hookworms (Ancylostoma caninum) Whipworms (Trichuris vulpis) Tapeworms (Diplylidium caninum, Taenia pisiformis, Echinococcus granulosus, and Echinococcus multiocularis) Heartworms (Dirofiaria immitus) Worming and examinations for parasites should be based on circumstances such as the age of the dog, likelihood of exposure to feces from other animals, use of a heartworm preventive that also controls intestinal parasites, previous infections, breeding plans and children who play with the dog. The American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that puppies be dewormed every 2 weeks until 3 months of age and once a month from 3 to 6 months of age. Adult dogs should be treated regularly, approximately four times a year. The frequency of treatment will depend on the type and prevalence of the parasites in an area. Bitches should be dewormed once before mating and once at parturition. Nursing females should be treated at the same time as the puppies. New dogs should be dewormed immediately and again two weeks later before following the recommendations. Many veterinarians suggest dogs should have an annual fecal examination performed. Fecal examinations detect the presence of intestinal parasites. Fecal examinations can also reveal the type of parasites so the proper medication will be selected. A variety of commercial products are available for treating internal parasites and a veterinarian needs to be consulted for the best product. Roundworms, hookworms and tapeworms of dogs can cause serious disease in people, especially children who may not have good hygiene habits. Treating a pet for worms is important for the health of the pet as well as the health of the humans caring for the dog. Testing for and preventing heartworms depends on how common heartworm disease is in the area and how long the mosquito season lasts. Mosquitoes transmit heartworm by spreading the microfilariae larvae. Prevention of heartworm is achieved by daily doses of diethylcarbamazine (DEC) or monthly minute doses of ivermectin. External Parasites: Fleas are the most common external parasite of dogs. Both cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) and dog fleas (Ctenocephalides canis) infest dogs. They are wingless, brown, bloodsucking insects. Controlling fleas involves treating the animal along with the environment. Demodectic mites (Demodex spp.), sarcoptic mites (Sarcoptes spp.), ear mites (Otodectes cyanotis), walking dandruff mites (Cheyletrilla yasguri) and lice (Trichodectes canis and Linognathus setosus) can all infest dogs. Effective treatments for fleas, mites and lice include rotenone, methoxychlor, diazinon, malathion, coumaphos, lindane or chlordane. A veterinarian can recommend the best treatment for the type of parasite. Ticks are bloodsucking arthropod parasites. Depending on the type of tick involved, the dog may be a host for the tick to complete its life cycle. Once the tick is attached to the dog it must be removed. Control of ticks is similar to the control of fleas. Noninfectious Diseases: Many of the noninfectious diseases of dogs are similar to well-known human diseases such as heart disease, cancer, cataracts, glaucoma, hip dysplasia, arthritis, night blindness, tetanus and botulism. Because of their close association with humans, dogs are also subjected to possible poisonings by insecticides, plants, household chemicals, herbicides, medications, metals and antifreeze.