TWELVE HOURS WITH THE GOTHIC ROMANCE

advertisement

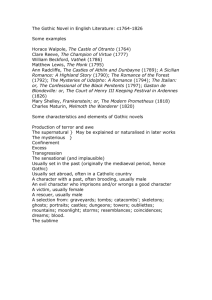

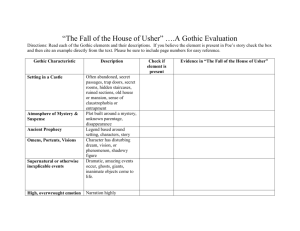

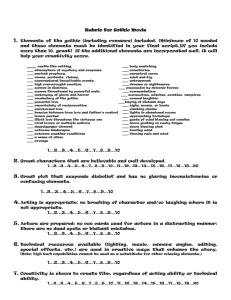

Twelve Hours With The Gothic Romance Asistent universitar doctorand Mara Magda MAFTEI Academia de Studii Economice, Bucuresti This paper deals with a brief presentation of the term Gothic, of its origin and its influence upon different writers starting with William Langland and including both philosophers and essayists. I continued with the analysis of the major Gothic authors in British literature such as: H. Walpole, C. Reeve, A. Radcliffe, G. R. Lewis, Ch. R. Maturin and M. Shelley but also with the influence their best works had on the afterwards literature. Even if all the seven writers aforementioned belong to the same literary trend and they display the same kind of information, their narrative structures have different functions. Introduction The target of the Gothic writers is to bring about emotions under the cover of pity and fear but especially fear because it is the most connected to sublime. In the Middle Ages the combination of the Gothic vault in architecture with the new orthoscopic model determined a sense of equilibrium in William Langland's “Piers Plowman” and in Chaucer's work. “The Augustan poets” professed the same equilibrium and liberty in expressing anxiety as opposed to the sensible illuminists. The dream-vision allegory and the dream bestiary in Chaucer's The Parliament of Fowles descend right in the Gothic school. That is why Beverly Sprague Allen talked about the “survival” of the Gothic in England not its “revival”, about the Gothic as part of the pre-Romantic and Romantic sublime. In England the term “Gothic” was used pejoratively, it expressed violence, primitivism, and the preference for supernatural elements. But the meaning of "Gothic" has evolved since; W. Hogarth in his "Analysis of Beauty" annihilates the clearness professed by Chaucer and the Augustan poets considering the winding as "the line of beauty". Out of an existential beauty, Shakespeare and Milton defalcated the variety and the difficulty of their tragedies (according to W. Hazlitt, Shakespeare is the model of the Gothic romance). The Gothic romance breaks down in panic and anxiety, both issued in the conscience of those who have not attained yet the essence of the world proclaimed by Prévost and François Thomas Marie de Baculard d'Arnaud, the creator of the “sober genre”. This entire influential game descends in a straight line, as a metastasis of the Gothic school, to the past. The publication, in the romantic period, of the medieval ballads (collected in the second half of the century) influenced Coleridge’s work. As a result, he wrote the "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" and "Christabel". The forms of the Gothic developed by H. Walpole, C. Reeve, A. Radcliffe, G. R. Lewis, Ch. R. Maturin and M. Shelley are considered to be the major points in the "dark" sublime, a sublime generated by persons fighting with all the force they are capable of. The painful and elegiac impression is determined by both the incapacity of retorting and submission. Their influence is torn apart in works and masterpieces and finally prolonged to the modern thrillers. 1) H. Walpole's The Castle of Otranto Published in 1764, it meant the eruption of both the imaginary and the fantastic in a rational age. The modernity of his romance consists in a conjunction of a personal manner and the recent technique of shaping ideas and expressions. With Walpole the supernatural becomes possible. Manfred's temperate grief turns into pleasure and mystery in Blake's poetry; a far-fetched pleasure means pain to Fuselli. Art is haunted by dreams troubled by menacing visions. The Gothic castle of "Strawberry Hill" is a "grandiose demonstration of a new outlook's victory regarding the artistic ideals"1. Pip, Dickens's character in Great Expectations will arrive at London, meet a picturesque old man who has built up such a castle, adorned with a miniature tower for the imitation to be perfect. Byron's portrait gallery of Fatal Men (Manfred, Lara, The Corsair, The Giaour) traces a former ghastly passion. In Walpole, the dream is the reason of the whole construction as in Shelley's "The Triumph of Life", where the narrator-poet indulges in the fantasy of a "waking dream" recalling a haunted past and an allegory of death. The Castle of Otranto is a pseudo-historical novel as Edward Bulwer Lytton's The Last Days of Pompeii. Walpole's romance expresses a widely held cultural belief when he urges his putative daughter-in-law to marry him instead of his son. Godwin is preoccupied with the social-political values of literature as Walpole's atmosphere is wrapped in a background historical fact such as "Caleb Williams" and St. Leon, a story from the XVI century. 2) Clara Reeve's The Old English Baron (1777) Clara Reeve’s novel initiated the tradition of the female Gothic novel. According to Cynthia Griffin Wolff, the archetypal Gothic building with its walled exterior and too easily penetrated interior chamber's, "crypts and secret passages" represent the "woman's body when she is undergoing the siege of conflict over sexual stimulation or arousal". Clara Reeve developed a parallel theme to Walpole: the son of a noble recovering all his rights. The only Gothic elements are the dream and the mystery. "It is a modern sentimental story in a false historical frame"2. Wieland's Don Sylvio de Rosalva has some common points with The Old English Baron such as fidelity to historical truth, harmonious development of personality, liberty of the artistic imagination. The sets of the deserted rooms recall the lugubrious drawing room of Miss Havisham in Dickens’s Great Expectation, the food of the wedding feast covered with cobwebs, the dark wrapping a closed atmosphere. Edmund’s mysterious origin tends to be ideal, he is more like a type rather then fully-formed human being and he is related to his dead father in an abstract, symbolic way. This entire Universe of old legends, medieval and dark superstitions point to Poe's fiction (The Fall of the House of Usher, Metzengerstien, Berenice, Manuscript Found in a Bottle). But instead of his cherished landscape of nature, a ruined past and a gloomy castle are pictured. The romantic witz (named by Fr. Schlegel) is grasped in Edmund's ironic destiny and in his meeting with the devil (Poe's fiction) when fear is analysed in terms of an ironic detachment. Nightmares are fulfilments of desires. The phantom is called up by a present event, it reaches the past where an infantile experience was not entirely ended, and then it is projected into future where the wish come true but carrying the traces of both present and past. When the ghosts became almighty, the conditions generating neurosis are already created as in the case of signora Laurentini in A. Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho. 1 2 Summers Montague, The Gothic Spirit, London, 1941, p. 89 Baker Ernest A., The History of the English Novel, New York, 1957, p. 180 3) A. Radcliffe's The Mysteries of Udolpho. Ann Radcliffe typically used the medieval ruined castle or abbey as a metaphor for the female body, penetrated by a sexually attractive villain. Like Keats’s dreaming Madeleine in The Eve of St. Agnes, the reader is encouraged to participate imaginatively in an intensely erotic seduction but to wake "warm in the virgin moon, no weeping Magdalen". Jane Austen built up Northanger Abbey on the Gothic pattern starting with the main character, Catherine Morland. “She pities her portrait against Gothic mannerism also producing a mise-en-abyme, by making her heroine a Gothic addict, giving her to read from The Mysteries of Udolpho and other "horrid" books”3. As Jane Austin, Richardson shares with A. Radcliffe the capacity of creating an emotional atmosphere around his characters. The Castle of Udolpho reminds of Rochester's estate in Jane Eyre due to its architectural images and landscape descriptions. The road to the castle suggests the labyrinth. In Mrs. Radcliffe's novel, sympathetic figures, victims of the villain wickedness confront a set of unappealing figures. Emily Brontë situates at the centre of her novel, Wuthering Heights, the "dark" character, a descendant of the traditional "traitor", who is set outside all social conventions (but he resembles them only in external details). It is terror as source of the sublime that prevails in A. Radcliffe's novel, similar to Shakespeare and Milton’s work. From A. Radcliffe to Wordsworth and Coleridge the same perception of nature prevails, the same worship of landscape description, which originates in poetic sensitiveness. Schedoni in The Italian prepared the way to Byron's hero, that is a portrait built up on a single dimension controlling the epic frame. Byron adjusted his drama Werner to a Gothic romance Kruitzer, the Romance of the German by A. Radcliffe "elaborating a too ample portrait"4. The Count Ferdinand Fathom is associated both with Mrs. Radcliffe's Gothic pattern and the Gothic forerunner, Prévost. The "graveyard poets", Gray and Young combine a sober, reflective, melancholic and moral mood with the rehabilitation of rational dimension as in A. Radcliffe's. She offers the visual model of a sin scene, which from Lewis to Shelley and Rossetti will be used recurrently. On the other hand, the old recognition scene of the Greek romance becomes one of the mainstays of the "tales of terror" as it was to be of Romanticism in general. Parents who rediscover their children in the most dramatic circumstances: this was the main spring of the plays and novels of about 1830 (e.g.: Dumas's La Tour de Nesle, Victor Hugo's Lucrece Borgia). In the 19th century, John Ruskin did his best to re-establish the medieval term "Gothic" to mean "Christian". In Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter, the tragic is annihilated because Hester Prynne ignores the absolute limit and accepts to wear the letter A "formula of alternative possibilities". As A. Radcliffe does, Hawthorne explains the supernatural elements by showing their natural origin. Mystery prevails in the soft outlines of the dusk, finally reduced to an illusion. The governess in H. James's The Turn of the Screw suffers from hallucination, like Dorothée in The Mysteries of Udolpho who sees the ghost of her former "lady". The ghosts are also dramatic projections of Emily's own unconscious sexual desires and the result of their repression. By the 1930's F.M. Mayor and Isak Dinesen focus their tales upon a relatively enclosed space in which antiquated barbaric code prevails. Conan Doyle's story The Adventure of the Speckled Band is set within an ancestral mansion locked into an archaic form of domestic tyranny. Bret Harte's Selina Sedilia breaks the Gothic pattern in a parody. 4) M. G. Lewis's The Monk 3 4 Tupan Maria-Ana, A Survey Course in British Literature, Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti, 1997, p. 352 Doherty Francis M., Byron, London, 1968, p. 99 According to the Coleridgean principle of "reconciliation of opposites and discordant qualities", M. G. Lewis's characters are both demonic and fascinating. Lewis initiates the Romanticism. "The Gothic literature is the translation of a modern Promethean vision"5. But Prometheus is not the supreme tyrannical spirit, the hero is not his shadow, and Frankenstein is not the monster he creates. Ambrosio suffers from ambivalence: he is both victim of the demon and the saint turned into demon. The monk is a representative of the Satanic Romantic heroes, embodiment of both Prometheus and Satan. From Ronsard, the creator of titanism (in his "Hymns") to Lewis, the forerunner of Byron's Titans, the villain is punished according to the Romantic concept (Balzac's Lucien de Rubempre and Vautrin also suffer from a similar penalty). The image of the gulf in which he is crumbled down is a symbol of existential insecurity. The Monk generated the series of the "beautiful death", of patients not at all tragic for they have done nothing to move the boundary in its immobility such as: Hoffmann's Die Elixire des Teufels (Medardus's double personality); Grillparzer took from it the plot of Die Ahnfrau; W. Scott in "Ivanhoe" derived from "The Monk" the idea of the tragic love of the Knight Templar Bois-Guilbert for the beautiful Jewess Rebecca; Victor Hugo drew upon Lewis's romance for the character of the persecuted Esmeralda and for that of the infamous priest, Claude Frollo, and George Sand for those of Lelia and the priest Magnus. According to Baker "the only examples of the Gothic English which will matter in any sense followed Lewis's example"6. The line of the Fatal Woman, which forces the sober formula Anánke descends into Cleopatra in the Liber de Viris Illustribus, Velleda (Chateaubriand) and Salammbô (Flaubert), and on the other hand into Carmen (Merimée), Cecily (Sue) and Conchito (Pierre Louys) "as a counter point of the innocent Antonia seduced by the perverted monk Ambrosio and who also awakes like Shakespeare's Juliet in a fearful crypt among decayed corpses"7. As in Faust, the vision of Antonio undressing to bathe which the witch causes to appear in a mirror exemplifies the soma-sema motif (Bossuet "a mirror - a mortification - a challenge of death"). The Devil appears under the form of a very beautiful young man, his features overcast with melancholy as is suitable for a fallen angel of the Miltonic school (with a touch also of Eblis in Vathek). 5) Ch. R. Maturin Melmoth the Wanderer François Pagès called the "black manner" the "English manner".Considering Ch. R. Maturin the genius of the narrative inventiveness preoccupied with existential problems and the dark sides of the consciousness, Melmoth the Wanderer becomes an archetype of northern European Romanticism, linked in the popular imagination with Byron's Childe Harold and Cain, with Goethe's Faust, with Dostoevsky's Raskolnikov and with the legends of the "Wandering Jew" (Sanders, 1996:344). The modern settings of "sensation novels" resurface in the 1860's (Sheridan Le Fanu, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Wilkie Collins) and appear again towards the end of the century in more overtly Gothic works by Stevenson, O. Wilde, Bram Stoker. In Melmoth, the reader comes across the figure of the maiden born beneath an unlucky star, a younger sister of Goethe's Margaret. In his attempt to surpass the boundary of both human life and reality, Melmoth resembles Goethe's Mephistopheles, the Byronic hero, the vampire. The central episode (which is made up of several stories each keeping its autonomy like the The Arabian Nights or the masterpieces of Cervantes) consists of the love affair between Melmoth and Immalee under the veil of a character like Haidee in Byron's Don Juan ending in the name of Isidora and a destiny which relates her to Goethe's Margaret. Melmoth's classic end joins the "pure necessity" rule, because no character such as Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, Byron's Manfred, and Lewis’s Monk has its own law. 5 Bloom Harold, Postface to Mary Shelly in Frankenstein, New York, 1965, p. 223 Baker Ernest A., op. cit., p. 112 7 Praz Mario, The Romantic Agony, London, 1933, p. 25 6 Ch. R. Maturin proves the capacity of a psychologizing Gothic vision. There is a long story of a forced monastic vow derived from Diderot's Religieuse and turned into the terrors of the soul such as it is found only in Poe The Fall of the House of Usher, namely the decline and extinction of the old family line. 6) Mary Shelley's Frankenstein Mary Shelley's novel swerves from the female Gothic tradition because its central protagonist is not a woman. Female writers feel a closer affinity with nature, defined in Western culture as female or mother and hence with the non-figural or the semiotic (Julia Kristeva). In Frankenstein the repressed semiotic may return in the form of a monster that enacts his maker's desire for domination and at the same time literalises the death that is "at the heart of Western practices of Eros"8. “In other respects, Frankenstein is much more a matter of word-ing "death and grief", of reinscribing the archetypal rebel figure of the Romantic school: Milton's Satan, Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen, Werther, Faust, Prometheus, Schiller's Räuber, Coleridge's Mariner, Byron's Fatal Man, Shelley’s escapist, Alastor - haunted poet”9. As the creature awakens to a sense of self-awareness, he starts to ask himself the fundamental question which man alone among all creatures is able to ask (such as Milton's archetypal Adam in Paradise Lost: “Who was I?”, "What was I?", "Whence did I come?", "What was my destination?"). Unfortunately he had no destination, he is the messenger of death like any other “double”. As a human being the monster is capable of self-analysis and self-criticism; but as a "double" he embodies a fearful image (Dante's Hell, the spirits in Hamlet, Macbeth, and above all Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray). The ambition to create life, a Romantic shiver also touches Shelley's Hymn to Intellectual Beauty, Mont Blanc. But Frankenstein is far from being perfect; the tragedy is finally triggered (the evil happens when there is no love). Christina Rosseti considers her fable (Goblin Market) as original as the creation of Frankenstein was (the roots of her goblins are themselves mysterious). G. Eliot's memories of the ugly intellectual's girlhood also give us Gothic horrors. The monster is governed by a demonic enthusiasm, by pathos of experience that announces the Romantic sentimental figures such as Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights. He is a projection of the human mind that has created him; he embodies both knowledge and masterliness. The evil caused by the absence of love determines the final judgement. This is the Romantic parable also at high fashion in Shelley's The Sensitive Plant, due to the minute description of the passing from life to decay and death. Horror, pity and hate against tyrants are the springs of inspiration in The Cenci. But M. Shelley admires too much the depth of the gulf and suddenly the gulf watches her inner depth too. The melancholic results in the glance cast to the person staring at the gulf. When "Mathilda" sketches the incest, the author identifies her heroine with Dante's Matilda. A forerunner of Matilda is Le Diable Amoreux by Cazotte (1772) in which Biondetta, dressed up as a page (Biondetto) tries to make Don Alvaro fall in love with her. She is the Devil. Mathilda is considered the name of the forbidden woman. In M. Lewis's The Monk, Mathilda is the devil's handmaiden. In H. Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, Matilda is the daughter of the Gothic villain Manfred, who wants to divorce his wife and marry his dead son's fiancée, Isabella Percy. Shelley adopted the name of Matilda for the impassioned female protagonist of his own early Gothic tale Zastrozzi, a Romance (1810). By the middle of the 20th century people talked about a Southern American Gothic movement including among others William Faulkner’s A Rose for Emily, Carson McCuller's 8 9 Hartsock Nancy, Money, Sex and Power, New York: Longman, 1983, p. 36 Tupan Maria-Ana, op. cit., p. 342 Reflections in a Golden Eye, Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa (the nightmare of the void, horrifying settings), but also about an army post located somewhere in the South (Reflections in a Golden Eye). T. S. Elliot considerer Djuna Barnes's novel of 1936 a Gothic masterpiece in its "quality of horror and doom" (macabre fantasy interlacing lesbians, lunatics, Jews, spoiled priests, artists, noble men, transvestites); it has remained attractive to women writers10. Leslie Fiedler in his critical study Love and Death in The American Novel concluded that the central tradition of fiction in the United States had been predominantly Gothic from first to last. But the most outstanding Gothic work of recent years is the novel Beloved (1987) by the AfricanAmerican writer Tony Morrison. Conclusions The Gothic novel’s influence is nowadays even more detectable in British and America novels; the Gothic influenced different writers, starting with William Langland and including both philosophers and essayists. The paper analysed the impact of the major Gothic authors in British literature such as: H. Walpole, C. Reeve, A. Radcliffe, G. R. Lewis, Ch. R. Maturin and M. Shelley and their influence on the afterwards literature. Even if all the seven writers afore-mentioned belong to the same literary trend and they display the same kind of information, their narrative structures have different functions. BIBLIOGRAPHY: Baker Ernest A., The History of the English Novel, New York, 1957 Bloom Harold, Postface to Mary Shelly in Frankenstein, New York, 1965 Doherty Francis M., Byron, London, 1968 Hartsock Nancy, Money, Sex and Power, New York: Longman, 1983 Moers Ellen, History and Tradition in Literary Women, the Great Writers, London, 1977 Praz Mario, The Romantic Agony, London, 1933 Summers Montague, The Gothic Spirit, London, 1941 Tupan Maria-Ana, A Survey Course in British Literature, Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti, 1997 10 see Moers Ellen, History and Tradition in Literary Women, the Great Writers, London, 1977, p. 108