Goh LiTing (12) 4GY

Full History Performance Task Essay

“There are more continuities than change in the nature of pre-war nationalism from 1900 to

1941.” How far do you agree with the statement? EYA.

I disagree with the statement to a large extent as there are more changes than continuities in

the nature of pre-war nationalism from 1900 to 1941. Although there was still some perceptible

continuity, the 1920s marked a significant turning point in the development of nationalist movements.

Therefore, I agree with the statement only to a small extent.

In the 1920s, nationalist groups began to look beyond merely anti-colonialism and became

more forward-looking. They had an end in mind and established a clear concept of what the future

independent nation-state should look like. Some nationalist groups also progressed from exclusive

reformist social or cultural aims to create a more inclusive, territorial-based national identity that

appealed to more people.

For example, the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD), established in 1927, was an anticolonial and militant organisation that was bent on overthrowing the French using violent means.

However, it did not have a clear vision of the face of post-colonial Vietnam and “the very idea of

violent revolutions had become an end in itself”,i rather than the means to a new Vietnam. Unlike the

VNQDD, the Indochina Communist Party (ICP), which was established in 1930, was forward-looking

and wanted a Communist post-colonial Vietnam. It was able to look beyond anti-colonialism and

progress to full-fledged nationalism. In addition, the Dong Kinh Free School, founded in 1908,

emphasised the use of the Quoc Ngu instead of Chu Nom to promote cultural aims and introduced

exclusive social reforms such as the provision of education to the masses rather than to the elites.

However, it gave way to more inclusive, national independence movements like the Vietminh, formed

in 1941, which aimed to create a broad coalition of anti-colonial and anti-Japanese elements to

garner mass support.

Similarly, in Indonesia, the Budi Utomo, founded in 1908, aimed to promote social and cultural

reforms, which were in line with ethnic nationalism. It stressed regional Javanese identity and values

and advocated the creation of a ‘Greater Java’. However, as with the case of the Dong Kinh Free

School, it gave way to more inclusive organisations such as the Indonesia National Party (PNI), which

was formed in 1927. Unlike previous nationalist movements that emphasised regional or religious

identity over another, the PNI sought the creation of a common, inclusive Indonesian national identity

that successfully appealed to the masses in Indonesia.

Therefore, during the period of 1900 to 1941, the nature of pre-war nationalism changed from

one of exclusivity and resistance as an end in itself, advancing to one which was more inclusive,

territorial-based and resistance as the means towards the end—of an independent and progressive

state.

On the other hand, there was continuity in the nature of pre-war nationalism in that some

national groups continued to gain support through promoting the creation of a transnational

community based on religion. In Vietnam, Cao Dai and Hoa Hao, formed in 1926 and 1939

respectively, emphasised morality and spiritual beliefs, showing the continuation of religious

nationalism.

Likewise, in Indonesia, the Sarekat Islam, established in 1912, was a religious nationalist

group advocating pan-Islamism. Sarekat Islam “took on a messianic significance”ii as

“Tjokroaminoto’s name...was one of the traditional Javanese names of the expected deliverer” iii and

these religious references managed to mobilise traditional peasants. The Partai Komunis Indonesia

(PKI), formed in 1920, wanted Indonesia to be a part of the transnational Communist community and

establish Indonesia as a Communist state. However, it also obtained its mass support by appealing

to traditional beliefs in the supernatural—“The success of Socialist and Communist parties in

establishing mass memberships from the mid-1920s on can be attributed to the ‘adaptionists’ among

the organizers who allowed party principles to be carried by ‘traditional’, mainly religious, idioms of

protests.”iv Furthermore, during the PKI Revolt of 1926, the peasants were reportedly waving their

PKI membership booklets like amulets.v In Malaya, reformist Muslim groups such as the Kaum

Muda, formed in the early 1900s, also wanted to be a part of a pan-Indonesian Islamic community of

believers. Therefore, from 1900 to1941, there was also a measure of continuity as religion continued

to play a significant role in shaping the aims of nationalist groups.

In conclusion, although there was a small measure of continuity as religion still featured

strongly in the nature of pre-war nationalist groups, the period of the1920s was essentially a

watershed in the nature of nationalist movements. Many nationalist groups were increasingly able to

rise above exclusive regional identities and anti-colonialism to create a collective identity based on

territorial nationalism and the genuine desire for independence and not just to be rid of colonial rule.

Moreover, Communism emerged as a largely new force, having gained popularity after the Russian

Revolution in 1917, and leading to the creation of the ICP in Vietnam and the Malayan Communist

Party in Malaya, which were formed in 1930. Therefore, with the feature of Communism and the

advancement of nationalist groups to become more forward-looking, I agree only to a small extent

that there are more continuities than change in the nature of pre-war nationalism from 1900 to 1941.

899 words

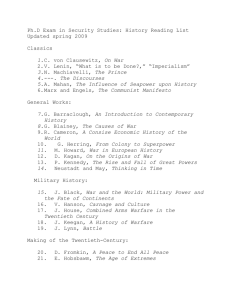

Bibliography:

Yong, M. (2007) From Colonies to Independent Nations: Selected Studies in Southeast Asian

History. Singapore: Pearson Longman

Wong, H.H. (2010) Unit 3.1 Nationalism in S.E.A. 1900-1945. Singapore: SCGS

Wong, H.H. (2010) Anti-colonial Movements from 1850. Singapore: SCGS

Ileto, R. (1999) “Religion and Anti-colonial Movements” in Tarling, N. (ed.) The Cambridge

History of Southeast Asia: Vol 3, From 1800s to the 1930s. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

i

Wong, H.H. (2010) Unit 3.1 Nationalism in S.E.A. 1900-1945: Vietnamese Nationalism. Singapore: SCGS

Wong, H.H. (2010) Unit 3.1 Nationalism in S.E.A. 1900-1945: Indonesian Nationalism. Singapore: SCGS

iii

Wong, H.H. (2010) Unit 3.1 Nationalism in S.E.A. 1900-1945: Indonesian Nationalism. Singapore: SCGS

iv

Wong, H.H. (2010) Anti-colonial Movements from 1850. Singapore: SCGS

v

Wong, H.H. (2010) Anti-colonial Movements from 1850. Singapore: SCGS

ii

![“The Progress of invention is really a threat [to monarchy]. Whenever](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005328855_1-dcf2226918c1b7efad661cb19485529d-300x300.png)