The Prosentential Theory of Truth

advertisement

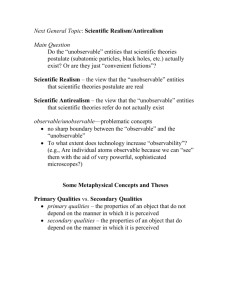

The Prosentential Theory of Truth. Beyond Realism and Anti-realism María J. Frápolli Departamento de Filosofía Universidad de Granada (Spain) frapolli@ugr.es 1. Conceptual Analysis The debate realism/antirealism comes in (at least) two flavors: metaphysical and epistemic; the semantic formulation of the debate due to Dummett that defines realism as related to classes of statements rather than to classes of entities 1 is reducible to one of the other two. There are theories of truth that explain truth as a metaphysical notion (“correspondence” to facts) and others that explain it in epistemic terms (coherence, or assertibility), and it is not infrequent that the realism/antirealism debate turns into the correspondence/coherence debate. Metaphysical realism states the independence of the reality around from our thought and will. A realist statement about a particular domain (metaphysics, ethics, esthetics, semantics, logic) is the acknowledgement of the existence of facts of the kind (i. e metaphysical facts, moral facts, esthetics facts, semantic facts, logical facts). The standard explanation in this context is that truth is correspondence with facts. Truth is ascribed to a proposition if there is a fact that makes it true. Epistemic realism, on its turn, states the objectivity of knowledge. Truth, knowledge, and objectivity lies thus on the side of realism. And antirealism is left with a picture in which a robust notion of 1 truth is not applicable, in which objectivity is not possible, and knowledge is substituted by subjective opinions and the relativity of perspectives. This is the standard view. Nevertheless, truth is neither a metaphysical nor an epistemic notion, and a complete account of truth that explains the meaning and use of a truth operator is compatible with any particular position in metaphysics and epistemology. The debate between realists and antirealists doubtless raises profound philosophical questions, but none of the parties is justified in claiming exclusive rights on truth, knowledge and objectivity. A partial reason that explains why truth is generally involved in metaphysical and epistemic debates lies in the fact that the truth operator is an indispensable instrument of propositional generalization and metaphysical and epistemic discourse essentially deals with general thoughts. I will argue that it is legitimate to ascribe truth to propositions and propositional contents independently of our realist or antirealist sympathies. The notion of truth doesn’t belong to this debate, to which it enters, as we have said, as an expressive tool, but is not essentially involved. Truths ascription play their role once that some propositional contents have been accepted. The home of the realism/antirealism debate is the justificatory level, i. e. how and why we assume that some contents are claimable; only after that truth appears in the picture. This point is particularly relevant for the question of realism/antirealism for it shows that there can be a neutral definition of truth that both parties, realists and antirealists, are allowed to use. Besides, removing the question of truth from the metaphysical and epistemic discussion clarifies both discussions, and permits individuate the actual difficulties related to the definition of truth in natural languages as much as those related to the structure of reality and our access to it. In these pages I will be concerned with an exercise of conceptual analysis. I will argue for the thesis that the notion of truth is not essentially involved in the debate between realists and anti-realists. It is, so to say, put at work in this debate but it does not belong to one side better than to the other. The theory of truth I would like to put forward, the prosentential theory of truth, is a technical proposal about the meaning of the truth operator in natural languages. Or more precisely, it describes an operator that in many natural languages (certainly in English, French, and Spanish) corresponds to the meaning of the truth predicate. Tarski already declared that his semantic theory of truth was neutral between the general, metaphysic and epistemic, philosophical views that one endorses. Although, on the other hand, the semantic theory of truth is related to the objectual interpretation of quantifiers that is one of the realists weapons. Truth is not an epistemic notion (my Canarias paper). Truth is not a metaphysical notion either. The basic tenet of a correspondence theory of truth is that truth is correspondence to facts. Yes, this tenet is correct, but unfortunately it is correct because it is empty. “is true” is a prosentence builder and the same is “is a fact”, defining truth as correspondence to facts is moving in circles. This is one of the reasons of the undeniable appeal that the correspondence theory has enjoyed throughout the centuries. Another reason is the ubiquitous representation account of content as provided by the referents of the expressions of language. C.J.F. Williams, and independently, R Brandom, have explained the actual conceptual poverty that lies under the correspondence view. It is legitimate to ascribe truth to propositions and propositional contents independently of our realist or antirealist sympathies. The notion of truth doesn’t belong to this debate, to which it enters, as we have said, as an expressive tool, but is not essentially involved. Truths ascription play their role once that some propositional contents have been accepted. The home of the realism/antirealism debate is the justificatory level, i.e how and why we assume that some contents are claimable; only after that truth appears in the picture. This point is particularly relevant for the question of realism/antirealism for it shows that there can be a neutral definition of truth that both parties, realists and antirealists, are allowed to use. Besides, removing the question of truth from the metaphysical and epistemic discussion clarifies both discussions, and permits individuate the actual difficulties related to the definition of truth in natural languages as much as those related to the structure of reality and our access to it. The truth predicate works, in natural languages, as a builder of prosentences. Prosentences are the equivalent in natural languages of propositional variables in artificial languages. A way of offering an exhaustive account of the meaning of truth in natural languages is following the threefold traditional distinction, due probably to Peirce and recovered by Morris, and explaining the syntactic, semantic and pragmatic roles performed by the truth predicate. Roughly stated, its syntactic job is restoring sentencehood; truth ascriptions are proforms of the propositional kind, and its semantic job, as it happens with the rest of proforms, is threefold: they work (i) as vehicles of direct propositional reference, (ii) as vehicles of anaphoric reference, and (iii) as instruments for propositional generalization. The pragmatic role of truth ascriptions is the endorsement of propositional contents, i.e. the explicit acceptance of propositional contents as appropriate items to serve as premises of inferential acts. Several different authors from different philosophical positions have pointed at the syntactic, semantic and pragmatic aspects of truth. The syntactic job of the truth predicate as a way of restoring sentencehood has been acknowledged from diverse points of view. Prior’s (Prior 1971) and Horwich’s (Horwich 1998) characterization of the truth operator as a denominalizer and also Quine’s disquotationalism all stress this syntactic feature. The view that is nowadays known as the prosentential theory of truth mainly focuses on the semantic job of truth ascriptions. Prosentences are a kind of proforms. Proforms are natural languages variables that serve as dummy expressions that reproduce the role of any instance of the logical category to which they belong. Pronouns are the best known among them, but they are not the only ones. There also are pro-adjectives, pro-adverbs and, as we will see, also prosentences. I have said that proforms reproduce the role of any instance of a logical category. And this needs an explanation. When linguists qualify an expression as a “pro-noun” they classify it in the category of singular terms, and in fact a pronoun is a term that can be substituted by any singular term salva gramatica. Nonetheless, the perspective I will take here is a bit different. I am classifying expressions according to their logico-semantic behavior rather than according to their syntactic status. The two ways of classifying pro-forms are not equivalent. Some syntactic pro-nouns are logically pro-adverbs, pro-adjectives or even pro-sentences. Terms like “it” and “that” can inherit any content whatsoever, and are thus all-purpose proforms. This will become clear in what follows. Ramsey (Ramsey 1927) was the first philosopher to use the term “prosentence” related to the truth operator. Almost 50 years after Ramsey’s work, Grover, Camp and Belnap (Grover, Camp and Belnap 1975), on the one hand, and Williams (Williams 1976), on the other, develop the prosentential account independently. From a pragmatic perspective, the truth operator makes explicit the speaker’s endorsement of a content. By qualifying a propositional content as true, the speaker commits herself to that content as something for which she is ready to give reasons, if required. By assuming a content as true, one is giving permission to use it as a premise in an inferential game. This aspect of the truth predicate has been put forward by Brandom (Brandom 1994). Strawson, when explains the role of truth as a marker of illocutionary force, hints at this pragmatic feature develop by Brandom. Nevertheless, Strawson’s treatment of the truth predicate doesn’t stop here and he also accounts for some of the syntactic and semantic features that I have related here as characteristic of the prosentential view2. I endorse the prosentential theory of truth and propose implementing it with the syntactic insights given by Prior and Horwich, on the one hand, and with the pragmatic picture developed by Brandom, on the other. All this, I maintain, represents a complete theory of how the truth operator works, it answers the essential philosophical questions traditionally related to truth, and also shows where and why most of the traditional treatments have gone astray. 2 In many of the cases in which we are doing something besides merely stating that X is Y, we are available, for use in suitable contexts, certain abbreviatory devices which enable us to state that X is Y […] without using the sentence-pattern “X is Y”. Thus, if someone asks us “Is X Y?”, we may state (in the way of denial) that X is not Y, by saying “It is not” or by saying “That’s not true”; […]. It seems to me plain that in these cases “true” and “not true” (we rarely use “false”) are functioning as abbreviatory statement-devices of the same general kind as the other quoted (1950, pp. 174-175). According to the prosentential theory, “is true” is a prosentence builder, and so is “is a fact”. Correspondentist theories that define truth by the equivalence “something is true iff it is a fact” or any variant of it don’t affirm anything wrong at the prize of not affirming anything at all. The claim that something is true iff it is a fact is shown by the prosentential account to be a generalization, whose appropriateness to represent a definition of truth cannot be assessed until its instances have been displayed. The insight behind redundancy proposals is explained relying on the syntactic character of the truth predicate as a denominalizer. In natural languages there also are nominalizers, i.e., operators whose jobs is converting non-nominal phrases into singular terms. Inverted commas and the particle “that” at the beginning of a sentence have this effect. If one applies a nominalizer to a sentence, inverted commas for instance, and converts it in a singular term, and afterwards applies a denominalizer, it is no wonder that one arrives at the same result with which one had begun. This is exactly what happens with Tarskian T-schema. Truth is not an epistemic notion. Even so, the truth predicate is omnipresent in epistemological discourse, and that not even the most basic theses in epistemology can be stated without essentially using the truth predicate. Besides, the endorsement role that the truth predicate performs in natural languages is applied in many cases to the items that have passed the kind of justificatory filters sanctioned by epistemology. The prosentential account can explain the insight that traces a connection between truth and justification; as the truth operator is a means of forming prosentences, i.e., propositional variables, it (or any equivalent operator) has to be around always that propositional generalizations are needed. The truth operator, in its generalization use, is the natural language counterpart of propositional quantifiers and proposicional variables of artificial languages. Epistemology and philosophy of science are paradigm contexts in which we deal with packs of propositions, and the only way natural languages have to talk about propositions in general is by means of propositional variables, i.e. prosentences. Truth is not a metaphysical notion either. Metaphysics is another context in which the use of prosentences is essential. The predicates “is true” and “is a fact” help to express metaphysical concerns. But here, as in the case of epistemology, the truth predicate is put at work; it is doing its job as a means of propositional generalization. If the prosentential theory is correct, then the analysis of truth is neutral with respect to the realism/anti-realism debate. This debate has to do with the structure of reality and our access to it. But the truth operator operates, so to say, at a second stage, i. e. it operates on the outputs of the justification processes. These processes can be positioned on any zone of the justificatory spectrum, they can be scientific procedures or assumptions of common sense, and they can be empirical or not, formal or not. All this belongs to epistemology and pragmatics, and would constitute the first step on top of which an explicit ascription of truth would be the second one. Mixing up the realism/anti-realism debate with the definition of truth is the effect of a poor understanding of the way in which the truth operator works. The debate realism/anti-realism surely tough upon fundamental philosophical questions, but none on which the truth predicate is essentially involved. References Brandom, R. (1994), Making it Explicit. Reasoning, Representing, and Discursive Commitment, Harvard University Press Grover, D., Camp, J., and Belnap, N. (1975), ‘A prosentential theory of truth’. Philosophical Studies, vol. 27, pp. 73-125. Also in Grover (1992). Horwich, P. (1998), Truth. Oxford Clarendon Press Kneale, W. and Kneale, M. (1962), The Development of Logic. Oxford Clarendon Press Prior, A. (1971), Objects of Thought. Oxford: Clarendon Press Ramsey, F.: (1929), “The nature of Truth”. N. Rescher y U. Majer (eds.), On Truth. Original Manuscript Materials (1927-1929) from the Ramsey Collection at the University of Pittsburgh, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991, pp. 6-24. Strawson, P. F.: (1950), ‘Truth’. In Simon Blackburn and Keith Simmons (eds.): Truth. Oxford Readings in Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 162-182. Williams, C.J.F.: (1976), What is Truth? Cambridge University Press