Cutting Off Utilities at Condemned Property public

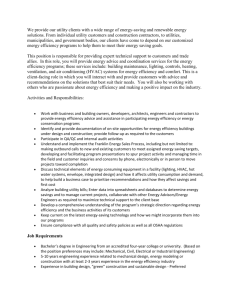

advertisement

March 13, 2009 Dear Sir: You have several questions related to the right of the city’s utility board to cut off utility service at property condemned by the city’s codes department, presumably for being unfit for human habitation. However, that authority appears to extend only to condemnation cases in which an emergency order of eviction has been issued. 1. What authority does the codes enforcement department have to terminate utilities for condemned properties of existing customers? Tennessee is in the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the law in the Sixth Circuit applies to Tennessee. The Sixth Circuit has developed rules governing the termination of utility services in condemnation cases. But the Tennessee state courts and the U.S. Supreme Court have also spoken at some length about the nature of utility services in Tennessee, and the protection those services are afforded under state law, but which are enforceable under federal law. What they have said has an impact upon all your questions on this subject. Utility Services Under Memphis LG&W v. Craft and Tennessee State Law Utility services in Tennessee are property rights Utility customers in Tennessee have property right in continued utility services. The U.S. Supreme Court held in Memphis LG&W v. Craft, 436 U.S.1 (1978), that such property rights could not be taken away except where two procedural safeguards were followed: - The utility must have in place a process for providing a termination notice. - The notice of termination must include notice that the customer has the right to a hearing, if he wants one, before the termination. Craft involved an unpaid utility bill. The Court declared that, “In defining a public utility’s privilege to terminate for the nonpayment of proper charges, Tennessee decisional law draws a line between utility bills that are the subject of bona fide dispute and those that are not.” [At 1560]. In the unreported case of Hargis v. City of Cookeville, 92 Fed. Appx. 190, 2004 WL 237655 (C.A.6 (Tenn.)), the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals also found that the city’s cut-off policy was defective because it did not notify the customer that he had the right to object to the termination of service, but also declared that Craft applied to cases of disputed water bills, and only when the cut-off had caused the customer damage. In that case there was no actual cut-off of utility service. However, it appears that whether or not an unpaid utility bill is in dispute, those two procedural safeguards apply to all utility terminations for any reason. Indeed, Craft was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court based on state law. State law is the source of property rights, but those rights are enforceable by the federal courts. That case declares that: State law does not permit a public utility to terminate service “at will.” Cf. Bishop v. Wood, 426 U.S. 431, 345-347, 96 S.Ct. 2074, 2078-2079 48 L.Ed.2d 684 (1976). MLG&W and other public utilities in Tennessee are obligated to provide service “to all of the inhabitants of the city of its location alike, without discrimination and without denial, except for good and sufficient cause,” [Emphasis is mine] Farmer v. Nashville, 127 Tenn. 509, 515, 156 S.W. 189, 190 (1912), and may not terminate service except “for nonpayment of a just service bill,” Trigg, 533 S.W.2d, at 733. An aggrieved customer may be able to enjoin a wrongful threat to terminate, or to bring a subsequent action for damages or a refund. Ibid. The availability of such local-law remedies is evidence of the State’s recognition of a protected interest. Although the customer’s right to continued service is conditioned upon payment of the charges properly due, “[t]he Fourteenth Amendment’s protection of ‘property’ ... has never been interpreted to safeguard only the rights of undisputed ownership.” Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67, 86 S.Ct. 1983, 1997, 23 L.Ed.2d 556 (1972). Because petitioners may terminate service “only for cause,” respondents assert a “legitimate claim of entitlement” within the protection of the Due Process Clause. [At 436 U.S. 11] In Smith v. Tri-County Electric Membership Corporation, 689 S.W.2d 181 (Tenn. Ct. App. 1985), citing Craft, above, it said that, “As in the case of water, electric utility service” is a “necessity of modern life” and the defendant is obligated to provide service to all its members “alike, without discrimination, and without denial except for good and sufficient cause.” [At 184] The Tennessee Attorney General in TAG 90-26, has opined that “Assuming a contract to obtain utility service is between a tenant and the utility, the Newport Housing Authority cannot disconnect these Utilities in order to enforce a writ of possession....” [At 1] The above cases appear to make it clear that where a person has legitimately obtained utility services, there is a contract for such services between the utility and the person. Does the condemnation of a structure constitute “good cause” to terminate the structure’s utility service by either the utility service provider or by the city’s codes department? The answer is that it depends on the reason for the condemnation and the process the utility service provider or the city’s codes department followed in making the condemnation. The Law On Utility Terminations In Condemnation Cases In The Sixth Circuit Flatford v. City of Monroe and other Sixth Circuit cases The Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals draws some fairly bright lines for the termination of utility service in codes enforcement cases. I will discuss those lines at considerable length to ensure that codes enforcement and utility service officers are aware of the questions they must ask themselves before they terminate utility services in condemnation cases. Flatford v. City of Monroe, 1 F.3d 162 (6th Cir. 1994), stands for the proposition that it is unconstitutional to evict homeowners or tenants without a pre-eviction hearing, except in cases of an emergency. There the Flatfords sued the city under 42 U.S.C. ' 1983, alleging that the when the city evicted them from their apartment it violated their procedural due process guaranteed to them under the Fourteenth Amendment, and their rights under the Fourth Amendment against unreasonable searches and seizures. In that case, police officers had entered the building in which the Flatfords lived to execute a search warrant unrelated to the Flatfords. But they saw what they considered to be numerous unsafe building conditions, and reported those conditions to the city’s Director of Building Safety. The Director obtained an administrative inspection warrant and visited the building accompanied by a city attorney. They found “numerous building code violations throughout the eighty-year old, wooden framed structure ranging from structural failure and extensive ‘wood rot’ to exposed electrical wiring and the presence of combustibles.” [At 165] The Director testified that the “extensive degree of dilapidation and disrepair was among the worst he had seen and feared that its tenants, including seven adults and sixteen children faced an immediate risk of electrocution or fire.” [At 165] He considered those conditions an emergency, and in consultation with the accompanying attorney, posted condemnation signs on all entrances, and with the assistance of city police officers, ordered the building vacated in 2-1/2 hours. [At 165] However, a detailed inspection shortly after the emergency eviction showed that most of the code deficiencies were in four units, while only a missing electric switch plate and an inoperative smoke detector in the Flatford’s apartment. But even affidavit of the owner of the apartment building showed that there were other electrical system defects in the building: .... that a splice in a wall switch could have been immediately corrected by shutting off the separately metered electricity to that apartment and disconnecting the illegal splice; that an extension cord running in the hall between two units could have been removed; that there was no storage in the stairway of combustible materialBno gasoline, oil, or the like-only household products stored in one unit in proximity to frayed electrical wire...[At 168] The question in this case was whether the code enforcement officials were entitled to qualified immunity for their actions. “The doctrine of qualified immunity,” said the Court: shields government officials performing discretionary functions from civil damages liability as long as their actions were reasonable in light of the legal rules that were clearly established at the time of their conduct. Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800, 102 S.Ct. 2727, 73 L.Ed.2d 397 (1982). Although the reasonableness of an official’s action turns on objective factors, the Supreme Court requires a fact-specific inquiry to determine whether officials would reasonably, even if mistakenly, believe their actions are lawful. Anderson v. Creighton, 483 U.S. 635, 639, 107 S.Ct. 3034, 3038-39, 97 L.Ed.2d 523 (1987). To withstand a motion for summary judgment on the ground of qualified immunity, the plaintiff must establish: (1) an alleged violation which implicates clearly established law, and (2) facts sufficient to create a genuine issue of fact that the alleged violation of that law actually occurred. Russo v. City of Cincinnati, 953 F.2d 1036, 1043 (6th Cir. 1992). The problem for judges in qualified immunity cases has not been in the articulation of the rule, but its application, said the Court, and: The decision will depend on a judgment or intuition more subtle than any articulate major premise. Thus we must settle whether the Flatfords’ version of the facts provides that the defendants did not act reasonably. Russo, 953 F.2d at 1043.... We must, therefore, determine whether Bosanac [the Director of Building Safety] is qualifiedly immune for his failure to provide the Flatfords with any process before or after the eviction. [At 166-67] The Court recited the rule governing evictions in Fuentes v. Shevin, below: In Fuentes v. Shevin. the Supreme Court held that due process requires notice and a hearing prior to eviction. 407 U.S. 67, 92 S.Ct. 1983, 32 L.Ed.2d 556 (1972). There are, however, “extraordinary circumstances where some valid governmental interest is at stake that justifies postponing the hearing until after [eviction].” Id. At 82, 92 S. Ct. at 82. A prior hearing is not constitutionally required where there is a special need for very prompt action to secure an important public interest and where a government official is responsible for determining, under these standards of a narrowly drawn statute, that it was necessary and justified in a particular instance. Id. At 91, 92 S.Ct. At 2000. [At 167] [Emphasis is mine.] The “statute” in this case was a provision of the Monroe City Ordinance that provided that: “If the building or structure is in such condition as to make it immediately dangerous to life, limb, property or safety of the public or its occupants, it shall be ordered vacated.” Monroe, Mich. Ordinance No. 89-018, ' 1 adopting by reference Unif. Bldg. Code ' 403(2) (1988). Protecting citizens from an immediate risk from an immediate risk of serious bodily harm falls squarely within those “extraordinary situations” contemplated by Fuentes. The Flatfords therefore have a clearly established right to a pre-eviction hearing only in the absence of exigent circumstances. [At 167] Did such an emergency exist? That question was pertinent to both the codes enforcement officer and to the police officers who assisted in the eviction in this case. The codes enforcement officer was the Building Safety Director, Bosanac, who the court concluded had acted reasonably in ordering their eviction. The Flatfords lived in one apartment in the apartment building. The Court reasoned that the apartment building must be looked at as a whole: We must examine the Flatford’s evidence concerning the condition of the structure as a whole not merely the condition of the Flatford’s unit in isolation of the units directly below. No one can seriously suggest that where there is a reasonably significant risk of fire, the installation of a smoke Director alone would guarantee the safety of children in adjacent apartments. Sometimes children are left alone. Dangerous conditions do not limit their consequences to the walls of a particular apartment. As a result, it was imminently reasonable for Bosanac to consider that the Flatfords’ safety required more than mere installation of a smoke detector in one apartment. [At 167] For that reason, the Court held that Bosanac had qualified immunity for his failure to provide the Flatfords with a pre-eviction due process hearing. But he was not off the hook: he had also failed to give the Flatfords notice of their right to a post-eviction hearing, although he had afforded that right to the landlord. For that failure, the Court held that Bosanac acted unreasonably. The court analyzed the question of whether the police officers had qualified immunity against the Flatford’s charge that they had violated the Fourth Amendment in assisting in their eviction without a warrant or a court order, and answered that question this way: Whether the officers violated the Fourth Amendment or whether exigent circumstances in fact justified the warrantees eviction, however, does not resolve the issue of qualified immunity. In Anderson v. Creighton, the Supreme Court cautioned that law enforcement officers whose judgments in making difficult determinations are objectively, legally reasonable should not be held personally liable in damages for conduct which, under Fourth Amendment academics, constitute a violation. 483 U.S. at 643-44, 107 S.Ct. At 3040-41. Further, stated the Court: We have recognized that it is inevitable that law enforcement officials will in some cases reasonably but mistakenly conclude that probable cause is present, and we have indicated that in such cases those officialsBlike other officials who act in ways they reasonably believe to be lawfulBshould not be held personably liable. The same is true of their conclusions regarding exigent circumstances... Id. At 641, 107 S.Ct. At 3039 (citation omitted). The very point of the exigency exception under these circumstances is to allow immediate effective action necessary to protect the safety of occupants, neighbors, and the public at large. Although police officers may have some knowledge of what constitutes a “dangerous building” as defined under municipal building codes, requiring officers to second guess the more informed judgement of a building safety inspector would hinder effective and swift action. Officers should, therefore, have wide latitude to rely on a Building-safety official’s expertise where that expert determination appears to have some basis in fact. [At 170] But in Footnote 7 of that case, the court went even further with respect to the qualified immunity of police officers, but also added a cautionary note: This is one in which officers faced some indicia of an emergency. We are not prepared to say, however, that such indicia are predicate to an officer’s reliance upon an inspector’s decision to evacuate. Given the need for swift action once an inspector has determined that conditions impose an immediate hazard, officers have no duty to test whether the decision has any basis in fact, e.g., that there is exposed wiring, electric splices, etc. Qualified immunity should ordinarily apply in these situations even where officers are unaware of the precise conditions that an inspector concludes, in his judgment, constitutes an immediate hazard. This immunity, however, remains qualified. If there are suspicious circumstances which would lead a reasonable officer to scrutinize whether an inspector’s actions are wholly arbitrary, then reliance upon the inspector’s judgment should not shield officers who act unreasonably.... [At 170] The unreported case of Sell v. City of Columbus, 47 Fed.Appx. 685, 2002 WL 2027113 (C.A. 6. Ohio), the Sixth Circuit considered the question of whether the summary eviction of homeowners by the city’s codes enforcement officers was legally justified on health and sanitation grounds. The “emergency eviction form” stated: Inspection of the above referenced site reveals that an emergency exists which requires immediate action to protect the public health and safety. The conditions causing this emergency to exist are as follows: Unsanitary conditions due to amount of pets. [At 686] The U.S. District Court had found that the eviction was legally justified because 33 dogs were found on the property, 21 of which were kept in the house. But an inspection of the home had been performed by the Public Health Veterinarian about three weeks before the eviction, but he found the premises to be “relatively clean,” “did not find any bowel movement or droppings or anything like that on the floor,” and “did not find that the number of dogs posed ‘an imminent health risk’ to either the canine or human occupants.” [At 687] The code enforcement officer testified that on the day of the eviction he signed the emergency order for eviction based on “presence of animal feces and urine on the floor, which he believed posed a health risk.” [At 688] However, the city’s emergency vacation order form provided an abatement option, but the code enforcement officer “did not provide plaintiff’s with an opportunity to clean the home or cause it to be cleaned, or to remove some or all of the dogs.” Rather, he issued a written directive to “VACATE PROPERTY IMMEDIATELY.” [At 688] Subsequent to the eviction, the codes department found other violations, including lack of smoke alarms, an unsafe heating system, a clogged drain in the basement, and roach and flea infestation. [At 689] [Note: None of the parties contested the District Court’s findings that the city could not rely upon after-discovered code violations to justify the emergency eviction order.] There was conflicting testimony by the Sells and the codes enforcement officers whether there the house was the presence or the smell of dog feces and urine and garbage of other kinds in the home. The District Court found “virtually overwhelming evidence” about the condition of the home, and that it supported a “reasonable conclusion by Cross and other Code Enforcement Officers that there was an immediate health risk to plaintiffs.” [At 689] The Court of Appeals rejected the District Court’s holding, declaring that: At least since the time of Sir Edward Coke, it has been a fundamental principle of Anglo-Saxon law that “a man’s home is his castle.” Institutes, III, 73. Accordingly, “the prohibition against the deprivation of property without due process of law reflects the high value, embedded in our constitutional and political history, that we place on a person’s right to enjoy what is his, free of governmental interference.”: Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67, 81, 92 S.Ct. 1983, 32 L.Ed.2d 556 (1972). (citation omitted [by the court]) The constitutional right to a hearing prior to eviction from one’s home is well established. See Fuentes, 407 U.S. at 81-82; see also Flatford v. City of Monroe, 17 F.3d 162, 167 (6th Cir. 1994). To put it simply, the guarantee of a pre-eviction hearing is the rule dictated by the Constitution. However, there is an exception to that rule. The Sixth Circuit recognizes a resident’s constitutional right, grounded in the Fourth Amendment and the Due Process Clause, to “pre-eviction judicial oversight in the absence of emergency circumstances.” Flatford, 17 F.3d. at 170. The “emergency circumstances” exception is carefully tailored: A prior hearing [before eviction] is not constitutionally required where there is a special need for very prompt action to secure an important public interest and where a government official is responsible for determining, under the standards of a narrowly drawn statute, that it was necessary and justified in a particular instance [At 690] [emphasis is mine.] In other words, the due process requirement of a hearing prior to eviction may be bypassed only if an authorized government official, adhering to limited statutorily prescribed standards, finds that immediate eviction without a hearing is “necessary and justified” to further an important governmental interest, most commonly the protection of its citizens’ health and safety... [At 690] The Court of Appeals was persuaded that the “undisputed accumulation of feces in the inside dog cages, alone, provided a reasonable basis for a Code Enforcement Officer to declare an emergency.” [At 697] But the record, continued the Court, did not indicate whether the existence of an emergency made it necessary to order the Sells to vacate the building without first affording them a pre-deprivation hearing. [At 697]: As a general principle, the Constitution allows summary eviction without the procedural due process of a pre-deprivation hearing only when necessitated by exigent circumstances to “[p]rotect citizens from an immediate risk of serious bodily harm.” Flatford, 17 F.3d at 167. In Flatford, for example, the building inspector found exposed wiring and improperly stored combustibles in a wood-framed apartment building, which he reasonably believed posed “an immediate risk of electrocution or fire.” Id. At 162. Similarly, in Mitchell v. City of Cleveland, No. 97-4206, 12998 WL 898872 (6th Cir. Dec 17, 1998,) the building inspector testified that “the inadequate and defective electrical system, constituted cause to order the building vacated to prevent serious injury or death.” Compare Zakaib v. City of Cleveland, No. 77402, 2001 WL 406209 (Ohio Ct. App. April 19, 2001) (drawing a distinction between unsanitary emergency conditions and emergency conditions necessitating an eviction without a hearing). [At 697] The Court of Appeals remanded this case to the District Court to make certain finding on questions about which the court was not clear. I do not know what happened to this case after that, but I use it for the purposes of pointing out that health and sanitation defects in buildings can also be the basis of emergency evictions, although I suspect that emergency evictions made on those grounds are more problematic than are ones based on electrical and structural defects, unless the health and sanitation defects involve plumbing defects that create human sewerage problems. But Sell v. City of Columbus cites two other cases in which the courts have upheld the summary eviction of tenants from buildings without pre-eviction hearings on emergency grounds: the unreported Sixth Circuit case of Mitchell v. City of Cleveland, 1998 WL 898872 (1998), and the Ohio Court of Appeals case of Zakaib v. City of Cleveland, 2001 WL 406029 (2001) Both cases involved police searches based on evidence of drug dealing in the residences in question in which the police reported code violations to the city building departments. Upon those reports the city’s building department obtained administrative search warrants and inspected the buildings for code violations. In Mitchell, the administrative search disclosed “faulty heating facilities, lack of smoke detectors, and hazardous electrical conditions,” which were declared by the inspectors to be a “public nuisance, constituting an imminent danger and peril to human life and public health, safety and welfare.” [At 1] Under a city ordinance, “immediate danger to human life or health is an emergency that authorizes the commissioner [apparently of the Drug House Task Force (DHTF)] to enter the property to remove the structure, make it safe, or order immediate vacating and boarding” [At 1] In this case the house was boarded up and the Mitchells were ordered to vacate the premises the same day. Similarly, in Zakaib, the administrative search disclosed a wide range of violations in a building that housed a grocery store and upstairs apartment: - Gas and electrical: Gas leak, combined with electrical violations created explosion hazard. The electrical defects included dangerous use of extension cords to power ungrounded soft-drink coolers, running next to gas furnace that had a leak. Wiring in upstairs apartment showed signs of an electric fire at a wall outlet, open electrical junction boxes and loose wire connections with electrical tape rather than wire nuts; Romex electrical wire used in a commercial building, and light fixtures in upstairs apartment were unsecured and hanging. - Plumbing: Main sewer line was plugged, causing raw sewerage to leak directly into basement where food products were stored, toilet in store bathroom was not secured to the floor, lavatory waste drain was not sealed on main floor of store, lavatory was not vented and sump pump fittings were with packing/scotch tape, flue connect to gas hot water tank was pitched downward which would result in carbon monoxide being pumped into basement and entire premises. - HVAC: Open, unsealed and improperly pitched flues for carbon monoxide venting, natural gas line leak, open and exposed wiring and safety controls for furnace; gas curb box had been covered with cement when driveway was poured, which prevented outside gas shut-of in an emergency, gas lines improperly installed, outside air conditioning unit installed without covers on electrical components, furnaces installed without permits and had never been inspected. - Structural: Rotten floor joists beneath high weight fixtures on floor of store, completely open and exposed stairwell pit in rear of premises, garage full of debris which was structurally unsound and created potential for collapse, toilet not secured to floor and rotten floor around it. - Health violations: Various food and cooking violations. Needless to say, all of those violations led to an emergency condemnation of the property without a pre-eviction hearing. In both Mitchell and Zakaib, the Sixth Circuit and the Ohio Court of Appeals, respectively, citing Flatford and Sell, held that the evictions of the tenants of the buildings were justified without a pre-eviction hearing. It is interesting that the courts in those cases rejected the administrative searches as being pretextual, that in reality the city was using the code enforcement process to shut down drug houses. The courts declared that the motive of the code enforcement officers was immaterial, that the issue governing whether the tenants’ utilities could be terminated was whether the code violations were so serious as to justify an emergency eviction. Application of Above Cases To Existing Utility Customers Generally Both Craft and the Tennessee cases on the nature of utility services in Tennessee, demonstrate that utility services create a property right in such services, which can be taken away only “for good and sufficient cause.” The Sixth Circuit in Flatford and the unreported cases cited above that rely on Flatford, cited the rule for emergency termination of utility services: In Fuentes v. Shevin. the Supreme Court held that due process requires notice and a hearing prior to eviction. 407 U.S. 67, 92 S.Ct. 1983, 32 L.Ed.2d 556 (1972). There are, however, “extraordinary circumstances where some valid governmental interest is at stake that justifies postponing the hearing until after [eviction].” Id. At 82, 92 S. Ct. at 82. A prior hearing is not constitutionally required where there is a special need for very prompt action to secure an important public interest and where a government official is responsible for determining, under these standards of a narrowly drawn statute, that it was necessary and justified in a particular instance. Id. At 91, 92 S.Ct. At 2000. [At 167] [Emphasis is mine.] Narrowly drawn statute requirementBYour City’s building codes Going backward in that language, there must be a narrowly drawn statute that supports emergency utility terminations. Flatford allows the statute to be a city ordinance. In Title 12 of the Municipal Code, the City has adopted several national codes that have a bearing on the city’s questions about the termination of utility services. The city has also adopted other codes in Title 12 of the Municipal Code, including electrical and plumbing codes. I have focused on those codes that I think answer the City’s questions. International Property Maintenance Code and International Fire Code. In Title 12, Chapter 5 of the Municipal Code, the city has adopted the International Property Maintenance Code, 2003 Edition (hereinafter referred to as the IPMC) [although the title page of Title 12, indicates that Chapter 5 applies to the Housing Code]. It has also adopted the International Fire Code, 2003 Edition, (hereinafter referred to as the IFC ) in Title 7, Chapter 2 of the Municipal Code. Section 107of the IPMC provides for notices of codes violations, ' 108 provides the standards for unsafe structures and equipment, and ' 109 provides for emergency measures, as follows: 109.1. Imminent danger. When, in the opinion of the code official there is imminent danger of failure or collapse of a building or structure which endangers life, or when any structure or part of a structure has fallen and life is endangered by the occupation of the structure, or when there is actual or potential danger to the building occupants or those in the proximity of any structure because of explosives, explosive fumes or vapors or the presence of toxic fumes, gases or materials, or operation of defective or dangerous equipment, the code official is hereby authorized and empowered to order and require the occupants to vacate the premises forthwith. [Emphasis is mine.] The code official shall cause to be posted at each entrance to such structure a notice reading as follows: “This Structure Is Unsafe and Its Occupancy Has Been Prohibited by the Code Official.” It shall be unlawful for any person to enter such structure except for the purpose of securing the structure, making required repairs, removing the hazardous condition or of demolishing the same. Section 110 of the IFC contains a provision for Unsafe Buildings, subsection 110.2 of which includes provisions for the immediate evacuation of unsafe buildings that have “hazardous conditions that present imminent danger to building occupants.” Section 109.1 of the IPMC itself appears to be more than adequate to support emergency evictions without a pre-eviction hearing. The one in Flatford provided that “If the building or structure is in such condition as to make it immediately dangerous to life, limb, property or safety of the public or its occupants, it shall be ordered vacated.” However, the Court in Sell was concerned that the eviction was being done by persons not authorized by the statute in that case. Section 4509.06 of the Columbus City Code provided that: (a) Whenever the Development Regulation Administrator finds that an emergency exists which requires immediate action to protect the public health and safety or the health and safety of any person, he may issue an order reciting the existence of such an emergency and requiring such action as he deems necessary.... But evidently, it was the city’s custom and practice of allowing code enforcement officers to order emergency evictions. The Court remanded the case to the District Court to make certain findings of fact, one of which was who, under the emergency eviction procedure, was actually authorized to order emergency evictions. Section 103 of the IPMC creates the department of property maintenance inspection, “and the executive official in charge thereof shall be known as the code official.” Section 109, governing emergency measures speaks of the “code official” as the person who makes emergency eviction decisions. Section 103.3 gives the code official the authority to appoint a “deputy code official, and other related technical officers, inspectors and other employees.” It is the “code official” who has all of the responsibilities of enforcing the IPMC. Common sense and the doctrine that generally says that administrative officials have the right to delegate administrative duties, suggests that the code official can delegate his duties, to subordinates, including the duty to make decisions in emergencies. But in light of Sell, it might be wise for any city to make sure that, at least where emergency evictions are concerned, the delegation of duty is found in writing. Qualified immunityBcode enforcement officers who terminate utilities Imperative in understanding and applying the doctrine of qualified immunity in preeviction cases is the Sixth Circuit’s position that it is unconstitutional to evict a person from his residence without prior notice and hearing. The only exception is when there are extraordinary circumstances that justify the denial of notice and hearing. In order to avoid liability for denying the person he evicted without a pre-eviction hearing the code enforcement officer must make a case that he had reasonable grounds to believe that the facts that led him to order the eviction without a hearing were extraordinary circumstances that satisfy the court. In Flatford the building inspector was held to have qualified immunity for his emergency eviction of the Flatfords without a pre-eviction hearing, but he was held not to have qualified immunity for his failure to give them a post-eviction hearing. If the conditions of the property in question are bad enough under Section109 of the IPMC, Flatford and the other cases above support the proposition that an emergency eviction will be allowed. But as the courts themselves said in those cases, each case depends upon the facts; there is no magical yardstick for determining whether the threshold for emergency eviction has been reached. The question of whether the emergency eviction will stand does not depend upon the code official being right, but whether he acted reasonably. It probably goes without saying that the violations in Flatford and Mitchell involved serious electrical code violations, the violations in Zakaib involved a serious combination of electrical and plumbing problems, and the violations in Sells involved serious health and sanitary problems, in that case with dog feces. Qualified immunityButility employees who aid code enforcement officers in terminating utilities Flatford’s analysis of the qualified immunity of police officers who aided the code enforcement officers in carrying out an emergency eviction of all the tenants in the building in which the Flatfords lived seems important in the context of utility employees who aid code enforcement officers in cutting-off utilities in emergency evictions. The Court gave the police officers broad qualified immunity, declaring that generally, the police officers should not have to second guess the officials who make the decision to evict tenants without a hearing on emergency grounds. The Court even went so far as to say that the qualified immunity of police officers did not necessarily depend upon the existence of an emergency in such cases, but in so saying, it issued a cautionary note worth repeating here: This [the case of Columbus v. City of Monroe] is one in which officers faced some indicia of an emergency. We are not prepared to say, however, that such indicia are predicate to an officer’s reliance upon an inspector’s decision to evacuate. Given the need for swift action once an inspector has determined that conditions impose an immediate hazard, officers have no duty to test whether the decision has any basis in fact, e.g., that there is exposed wiring, electric splices, etc. Qualified immunity should ordinarily apply in these situations even where officers are unaware of the precise conditions that an inspector concludes, in his judgment, constitutes an immediate hazard. This immunity, however, remains qualified. If there are suspicious circumstances which would lead a reasonable officer to scrutinize whether an inspector’s actions are wholly arbitrary, then reliance upon the inspector’s judgment should not shield officers who act unreasonably.... [At 170] But it appears to me that utility service personnel might have a higher duty than do police officers to “scrutinize whether an inspector’s action are wholly arbitrary” in cutting-off utilities, because utility workers are more experienced in the utility field. Section 111.3 of the IBC is somewhat vague on the question of whether the utility service provider has any voice in the termination of utility services where the codes enforcement officer decides that there is an emergency that requires the termination of such services. It provides that “The building official shall notify the serving utility, and wherever possible the owner and occupant of the building, structure or service system of the decision to disconnect prior to taking such action.” Nothing in that provision suggests that the utility service provider’s employees can second guess the code enforcement officer’s decision, only that he must give the utility service provider notice of his decision to terminate such services. In addition, it seems that generally, where there is an emergency eviction, utility services will ordinarily be cut-off because the building will be vacated. Indeed, ' 115 of the IBC, entitled UNSAFE STRUCTURES AND EQUIPMENT, also appears to apply to all structures, whether under construction or existing. Section 115.5 provides that: Structures or existing equipment that are or hereafter become unsafe, insanitary or deficient because of inadequate means of egress facilities, inadequate light and ventilation, or which constitute a fire hazard, or are otherwise dangerous to human life or the public welfare, or that involve illegal or improper occupancy or inadequate maintenance, shall be deemed an unsafe condition. Unsafe structures shall be taken down and removed or made safe, as the building official deems necessary and as provided for in this section. A vacant building structure that is not secured against entry shall be deemed unsafe. Sections 108.2, 108.5 and 19.2, of the IPMC respectively provide for the closing of vacant structures, the prohibition on the occupation of vacated structures, and the boarding up of such structures, all of which provisions strongly imply that utility services to them will be discontinued. Likewise, ' 311.2.1 of the IFC provides that vacant structures shall be “boarded, locked, blocked or otherwise protected to prevent entry by unauthorized individuals.” But ' 311.2.2 also provides that in vacant buildings, “fire alarm, sprinkler and standpipe systems shall be maintained in an operable condition.” What neither the IPMC nor the IFC do not cover is by whom utility services can be terminated. Common sense declares that if the electrical code violations are bad enough to justify an emergency eviction, the interest of surrounding property dictates that electrical service should be terminated. The same is true of water and perhaps sewer service in some cases. But your City has also adopted the International Building Code, 2003 Ed., (hereinafter referred to as the IBC), in Title 5, Chapter 1, of the Municipal Code. Generally, the IBC applies to new construction and alterations, but '' 111-SERVICE UTILITIES appears broader. Subsection 111.3 provides that: 111.3 Authority to disconnect service UTILITIES. The building official shall have the authority to authorize disconnection of utility service to the building, structure or system regulated by this code and the codes referenced in case of emergency were necessary to eliminate an immediate hazard to life or property. [Emphasis is mine] The building official shall notify the serving utility, and wherever possible the owner and occupant of the building, structure or service system of the decision to disconnect prior to taking such action. If not notified prior to disconnecting, the owner or occupant of the building, structure or service system shall be notified in writing, as soon as practical thereafter. Among the “codes referenced” in the IBC, are those specifically included in ' 101.4: 101.4. Referenced codes. The other codes listed in sections 101.4 through 101.4.7 and referenced elsewhere in this code shall be considered part of the requirements of this code to the prescribed extent of such reference. Two of the “referenced codes” are 101.4.5, the International Property Maintenance Code, and 101.4.6, the International Fire Prevention Code. As indicated above, the City has adopted both of those codes. The former code applies to: ....existing structures and premises; equipment and facilities; light, ventilation, space heating, sanitation, life and fire safety hazards; responsibilities of owners, operators and occupants; and occupancy of existing premises and structures. The latter code applies to: .... matters affecting or relating to structures, processes and premises from the hazard of fire and explosion arising from the storage, handling or use of structures, materials or devices; for conditions hazardous to life, property or public welfare in the occupancy of structures or premises; and from the construction, extension, repair, alteration or removal of fire suppression and alarm systems or fire hazards in the structure or on the premises from occupancy or operation. Read together, ''111.3, 101.4, 101.4.5 and 101.4.6 of the IBC appear to give the building official who enforces the IBC the authority to “authorize” the cut-off of “SERVICE UTILITIES” to property in situations where there the continuation of such services are an immediate threat to life and property. As pointed out above, the language in ' 111.3 appears to use the phrase “The building official shall have the authority to authorize the disconnection of utility service to the building....” in the sense that he can do it himself (or have his employees do it.). But even if that is so, as a practical matter he may find it necessary to call on utility officials to do that job. I have a passing familiarity with utility services sufficient to know that different methods can be used to cut-them off. As to electrical service, main breakers can be tripped for electrical service, but electric meters can also be removed and meter receptacles blocked. As to water and gas services, valves can be closed at or near the meter box or in the building at one or more places. Sewer service can be cut-off with sewer blocks, although I doubt that method is often used. There are probably also additional ways to ways to cut-off all utility services, and presumably, other considerations may go into how some services are cut-off. For example, in the winter, the decision to cut-off water might also involve draining water lines in the building. There may also be variations on how particular utility services are provided that may not make the cut-off of those services as simple as tripping one breaker or turning off one valve, especially where multiple tenants use a building. I can imagine that in many, or not all, cases the building official will want the utility service provider to do the actual utility cut-offs. It is in such cases that the qualified immunity question becomes more compelling for utility service workers, whose duty to make sure that the utility termination is not arbitrary may increase. How Does Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 68, Chapter 104, Part 1, Fit Into Your City’s Question? Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 68, Chapter 104, Part 1, contains lengthy provisions governing the inspection, and even the termination of electrical and gas services, but it does not appear to contain provisions for the emergency eviction of tenants. That statutory scheme gives the state commissioner of the department of commerce and insurance extensive authority in the area of fire prevention, including building inspections, and the authority to appoint deputy marshals to assist him. [Tennessee Code Annotated, '' 68-102-101, 68-102-104, 68-102-107, 68-102-116, and 68-102-117] Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 68-102-108 also makes certain persons “assistants to commissioner,” including the fire chief or fire marshal, depending upon the organization of fire services in the city in question. Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 68-102-117 contains provisions related to the regulation of dangerous buildings, among them, the following: (1) When any officer referenced in ' 68-102-116 finds any building or other structure that for want of repairs, lack of sufficient fire escapes, automatic or other fire alarm apparatus or fireextinguishing equipment, or by reason of age or dilapidated condition, or from any other cause, is especially liable to fire, or constitutes any other dangerous or defective conditions, and that is situated so as to endanger life or property, and whenever such officer shall find in any building combustible or explosive matter or inflammable conditions dangerous to the safety of such buildings, the officer shall order the dangerous or defective conditions removed or remedied and the order shall be immediately complied with by the owner or occupant of such premises or buildings, or by any architect, contractor, builder, mechanic, electrician or other person who shall be found responsible for the dangerous or defective conditions. The provisions of this subdivision (a)(1) shall apply to any building or other structure that is being erected, constructed or altered, and to any building that has been erected, constructed or altered. Subsection (2)(A) of that statute provides that AIf compliance is not expedient and does not permanently remedy the condition, after giving written notice, then the officer has the authority to issue a citation for the violation.... But subsection (c) provides that: If it is found by any person, association or corporation supplying electrical energy or gas (natural, artificial or liquid petroleum) to equipment or installations in any building or structure or on any premises located in this state, or if it is found by any official making an inspection pursuant to this chapter that such facilities or equipment are defective so as to be especially liable to fire or hazard to life and property, or to have been installed in violation of laws or regulations, then such person, association or corporation may discontinue the supplying of such electrical energy or gas until the defective or unlawful conditions have been corrected. That statute is puzzling as to whether the “person, association or corporation” that supplies the electricity or gas includes a municipal utility, and whether the utility cut-off can be immediate. Subsection (d) of the statute provides that: A supplier of electrical energy or gas to such installations having defective or unlawful conditions, as defined in this section or enumerated by a written report of any official making an inspection pursuant to this chapter, shall be furnished a copy of [any such order/s that] relate to the supplier, electrical defects to electrical suppliers and gas defects to gas suppliers. If the defective or unlawful conditions have not been corrected within the thirty-day period, then such suppliers, either electrical or gas, shall discontinue service until the defective or unlawful conditions have been corrected.... Jackson v. Bell, 226 S.W 207 (1920) is the only case I can find interpreting Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 68-102-117. But that case upheld the fire commissioner’s order under that statute to destroy a certain building that his inspection found to meet the “especially liable to fire” definition of that statute. [Also see the subsequent cases of Thomas v. Chamberlain, 143 F.Supp. 671 (D.C.E.D. Tenn. 1955), and Winters v. Sawyer, 463 S.W.2d 705 (Tenn. 1971)]. But the provisions in Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 68-102-117 related to who could cut-off electricity and gas, and when they could be cut-off were added after Bell. I traced the history of the development of that statute, but will omit it, except to say that it does not seem to me to qualify as a “narrow” statute of which Flatford speaks under which emergency evictions can be made without a hearing. Public Acts 1994, Chapter 193 added Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 68-102-153 to the statutory scheme in Tennessee Code Annotated, Title 68, Chapter 102, Part 1. Presumably, that addition gives to the fire marshal the authority to “disconnect or terminate electrical and gas service,” under Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 68-102-117, but only under limited conditions. I am not sure that statute constitutes a narrow statute that satisfies Flatford as one under which emergency evictions without a hearing can be made. It reads: (a) Neither the state fire marshal nor any inspector who contracts with the state may disconnect or terminate the electrical services at any residential customer’s residence until the following have been completed: (1) An inspection has been made of the premises that reveals that continued electrical services pose a substantial and immediate threat of harm to person or property, and the harm cannot be avoided by less drastic means other than disconnecting the service; (2) Reasonable attempts have been made to contact the customer or owner of the premises prior to disconnecting any services; (3) The person performing the inspection makes an examination of the premises to determine that there are no individuals using any medical devices that require electrical services, and, if so, reasonable accommodations are made to continue the electric service to medical devices following any termination; and (4) The person performing the inspection makes an examination of the premises to conclude that termination of the electrical services will not damage any property of the residential customer without first making arrangements to secure the prevention of the damages.... A significant exception to this statute is contained in subsection (b) of this statute: “The provisions of this section shall not apply to the personnel of any municipal electric system or any rural electric and community services cooperative.” Frankly, I am not sure whether that statute expands or narrows the authority of the personnel of municipal electrical systems to terminate electrical service. Arguably, it relieves such utility employees from performing the same checklist before cutting-off electricity. Under the provisions of the IBC cited above that give the building official the right to cut-off utilities, presumably, he too is not required by this statute to follow that checklist. But a reading of that checklist indicates that it is probably generally a good one to follow. 2. What authority does codes enforcement have to prevent new customers from getting utilities to condemned properties? If the building official has the authority under ' 111.3 of the IBC, to disconnect utility services to existing buildings through the “referenced codes” (IPMC, IFC, both of which the city has adopted),or through ' 115 of the IBC (Unsafe Structures and Equipment), to eliminate an “immediate hazard to life or property,” it stands to reason the building code official has some say: over the restoration of power, assuming an appeal has not overturned the building official’s decision to disconnect the utility services. Section 111.1 of the IBC seems to support that conclusion. It provides that: No person shall make connections from a utility, source of energy, fuel or power to any building or system that is regulated by this code from which a permit is required, until released by the building official. Section 102.3 of the IPMC also provides that “Repairs, additions or alterations to a structure, changes of occupancy, shall be done in accordance with the procedures and provisions of the International Existing Building Code.....” (Hereinafter referred to as the IEBC) The City has not adopted the IEBC, but '105.1 of that code requires permits on the part of [a]ny owner or authorized agent who intends to repair, add to, alter, relocate, demolish, or change the occupancy of a building or to repair, install, add, alter, remove, convert, or replace any electrical, gas, mechanical, or plumbing system, the installation of which is regulated by this code, or to cause such work to be done, shall first make application to the code official and obtain the required permit. There is also a Section 111BService Utilities section in the 2006 IEBC that has its exact counterpart in the IBC. Section 111.1 provides that provides that, ANo person shall make connections from a utility, source of energy, fuel, or power to any building or system that is regulated by this code for which a permit is required, until approved by the code official. Tennessee Code Annotated, ' 6-54-501 governs the adoption of various standard codes by municipalities in Tennessee, and requires official action on the part of the city to adopt such codes. I doubt that statute allows a city to treat the IEBC as adopted because in other codes the city has officially adopted it speaks of the IEBC as governing the particular question at issue. But if there is any doubt about whether the service utility provisions of the IBC allow the building official the right to prevent the owner or occupant, or a new applicant for service, from obtaining utility services for a condemned building, the city could adopt the IEBC. 3. If codes enforcement is authorized to do 1 and 2 above, what notice to the customer is required of the utility? This question also appears to be governed by Craft, and other cases above, which make it clear that in Tennessee continued utility service is a property right. But in Tennessee a property right also appears to be implicated where there is a denial of utility service as well as when the utility service is terminated. Needless to say, most of the cases dealing with the property right in utility services involve the termination of such services. However, one of the cases cited in Craft supporting the proposition that utility service is a property right is Farmer v. Mayor and City Council of Nashville, 156 S.W. 189 (1913) There Farmer sought to compel the city to provide him with water services at the residence he rented. At the time he rented the residence he tendered the proper amount to the city to secure waster service, but the city rejected his tender because there was a water “tax” outstanding on the premises. Under the city’s regulations, no water would be supplied to any premises where there was a debt owed for water service. In finding against the city, the Tennessee Supreme Court declared that: It was settled by this court in the case of Crumley v. Watauga Water Co., 99 Tenn. 420, 41 S.W. 1058, that a water company having the power under its charter to condemn private property for its necessary purposes, and obligated by the law of its creation to afford to the city of its location and the inhabitants thereof a plentiful supply of water, is a quasi public corporation, that enjoys and must exercise its opportunities for gain subject to its obligation to the public to supply water to all who apply therefor and tender the usual rates, and that this obligation is an implied condition of the grant of its franchises. It was also settled n Watauga Water Co. v. Wolfe, 99 Tenn. 429, 41 S.W. 1060, 63 Am.St.Rep. 841, that such a water company is charged with the public duty of furnishing water to all of the inhabitants of the city of its location alike, without discrimination and without denial, except for good and sufficient cause. [At 56 S.W. 190] For that reason, with respect to a person who attempts to obtain reentry to, and utility service at, the building where the person was subjected to an emergency condemnation and eviction, assuming the condemnation and the eviction were upheld on appeal and was not otherwise disturbed by a court, continues until the building is repaired sufficiently to satisfy the building inspector that it meets whatever code provisions apply to it, and the building inspector authorizes the reconnecting of utilities. It appears to me that essentially the same rule would apply to a “new” person applying for utility service at the condemned building. Craft and the cases supporting it that create a property right in Tennessee to utility services appear to allow the denial of utility services “for good and sufficient cause” as to the initial denial of utility services as well as to the denial of continued utility services. Requiring the building to be repaired and brought up to the standards required by the applicable building codes, and requiring the building inspector to approve the reconnecting of the utility services before the applicant for utility services can obtain such services seems to be within the scope of the building inspector under the building codes. To facilitate repairs to buildings, Section 111BService Utilities, in both the IBC and the 2006 IEBC, also provide for temporary connections in ' 111.2: “The code official shall have the authority to authorize the temporary connection of the building or system to the utility source of energy, fuel, or power.” In most cases where the restoration of utilities to a condemned building is being sought, the codes enforcement officials appear to be the prime movers, as they are when the decision to terminate the utilities is made. Presumably, the rules governing qualified immunity for the termination of utility services in condemned buildings applies to the denial of utility services in the same buildings, although the “denial” of utility services to a building after its emergency eviction and condemnation seems to be essentially a continuing part of the termination of utility services. Obviously, many condemned buildings will not be repaired; their owners will abandon them or will not otherwise spend the money to restore them to the standards prescribed by the various applicable building and utility codes. Some of them will be ordered demolished by the building inspector under the building codes and other statutes that allow such action. 4. Can you provide any suggested forms that utilities should require from code enforcement authorities [to disconnect and reconnect utilities]? Surprisingly, I have never been asked this question in all the years I have been at MTAS. I am in the process of trying to locate forms other cities or governments use when a decision is made by code enforcement authorities to terminate utilities for code violations. I will get back with you on this question as soon as I am successful. Sincerely, Sidney D. Hemsley Senior Law Consultant SDH/