Trevithick (2011) Understanding Defences-defensiveness

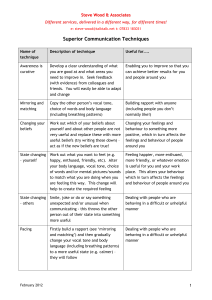

advertisement