BilingBank

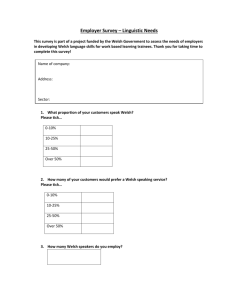

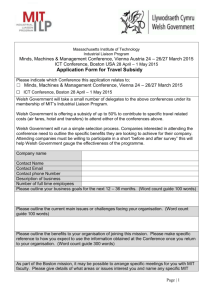

advertisement