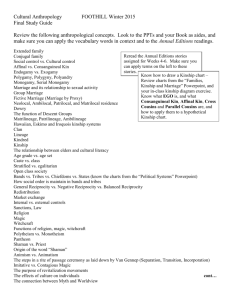

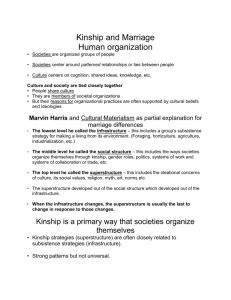

ANTH 2390 A02 Social Organization

advertisement