A short biography of Alfred Jarry

advertisement

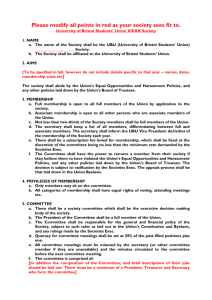

Celebrating brilliance, originality and spirit in the early works of some of the world’s great playwrights and theatre artists. For more information visit www.younggenius.org Ubu the King By Alfred Jarry Co-produced by Dundee Rep, Tron Theatre, the Young Vic and BITE:05, Barbican as part of YOUNG GENIUS First performed at the Tron Theatre, Glasgow on 3 November 2005 as part of YOUNG GENIUS Funders of the YOUNG GENIUS Schools’ Programme across the UK, including workshops, performance projects and free tickets for school students and teachers YOUNG GENIUS would not have been possible without the generous support of The Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, The Corporation of London, Arts Council England Grants for the Arts, Ingenious Media plc, The Jerwood Charity, the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, the Genesis Foundation and NESTA. UBU THE KING Resource Pack Contents Page 1. Alfred Jarry’s Life and Work 2 2. Table of Key Dates 4 3. A Brief Synopsis and Background to Ubu the King 5 4. Theatre in Alfred Jarry’s Paris 7 5. Social and Historical Context 9 6. Interview with the Director Dominic Hill 11 7. Creative Team 12 8. Design Images 13 9. About the Young Genius Season 15 10. Bibliography and Further Reading 16 If you have any comments or questions about this Resource Pack, please contact us: The Young Vic, Chester House, 1-3 Brixton Road, London SW9 6DE T: 0207 820 3350 F: 0207 820 3355 E: info@youngvic.org Written by Maria Aberg © Young Vic 2005 1 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 1. Alfred Jarry’s Life and Work Alfred Jarry was born on September 8th 1873 in the small village of Laval in Mayenne, France. His father, Anselme, was a travelling textiles salesman, and Alfred later referred to him as ‘an unimportant bugger’. Jarry was closer to his mother, Caroline, a headstrong woman with a great interest in literature, art and music. When Jarry began to show signs of academic excellence, Caroline decided to prepare her youngest son for university and moved to Saint-Brience in Brittany, leaving their drunken, unsuccessful father behind. Jarry became an academic wunderkind, winning praise and medals for his achievements in French, Latin and English. In 1888, Caroline sent the fifteen-year-old Jarry to the Lycée in Rennes to prepare for his university studies. His classmates at Rennes called him ‘Quasimodo’ because of his short, bowlegged figure, but nevertheless he made several good friends there. It was during this time that the original idea for Ubu Roi was born, in a satirical sketch written by Jarry and two friends which mocked an unusually fat and pompous maths teacher. In 1890, Jarry moved to Paris to continue his studies, and rapidly became involved in the lively literary scene, which distracted him from academia. He started attending Mallarmé’s famous ‘at home’ evenings, where well-known writers and thinkers of the time would discuss and debate current artistic phenomena, and he also attended the literary salon ‘Mercure de France’. Jarry cut a striking figure on the Parisian scene. Numerous descriptions of his colourful, eccentric fashion sense survive – he could often be seen wearing full cycling regalia, a tall stovepipe hat, a hooded cape and carrying a green umbrella. Once, he arrived at the Opera, wearing a paper shirt on which he had painted a black tie. His living arrangements were equally peculiar. His poky room in Boulevard Port de Royal was decked out with skulls and skeletons, he housed numerous owls, and at one point he built himself a house on the Seine with a hatch in the floor for fishing. In every aspect of his life, Jarry sought to upset the mundane and everyday, rebelling against the mediocrity of the bourgeoisie through excess and absurdity. He drank huge amounts of absinthe and smoked opium to expand his senses, and he rejected any authoritarian system or religion. In everything he did, he aimed for an exaggeration of reality, which would free the soul from the confines of a middle-class life. In 1893, Jarry caught the flu. His mother came to Paris to look after him, only to catch the flu herself and die as a consequence. Jarry was terribly upset, and failed his entrance exams to university. He signed up to take the test again the following year, but never did – instead he started drinking more heavily, and became increasingly involved in the literary scene. The following year Jarry was conscripted to the army; an experience he intensely disliked and which came to influence his later writings. He became very depressed during his period in the army, and in a mad scheme to get himself discharged, he injected himself with an acid which turned his skin yellow, and was sent back to Paris. His 1897 novel Days And Nights – A Novel of a Deserter vividly depicts his disgust with the military. Jarry became involved with the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre upon his return from the army, and managed to persuade the director to stage his now-finished play Ubu Roi. It opened on December 10th, 1896, after a riotous dress rehearsal for an invited audience. The play 2 UBU THE KING Resource Pack caused an immediate scandal with its explicit language and unconventional stagecraft, and was closed down after only one performance. In the years after Ubu Roi, Jarry’s health rapidly began to deteriorate. He continued to drink heavily and, because of financial problems, had to survive on a very poor diet. In 1904 he bought some land outside Paris, where he built himself a house and lived in absolute squalor, before becoming so ill that he had to move to his sister’s house in Laval to be cared for. He never fully recovered. He moved back and forth between Laval and Paris, suffering malnutrition and inhaling ether to keep the hunger at bay. He died in hospital from tuberculosis, in November 1907, aged 33. His final words were ‘Bring me a tooth pick’, to the last refusing to acknowledge authority or religion. 3 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 2. Table of Key Dates 1859 Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species is published. 1861 The creator of the ‘well-made drama’, Eugène Scribe, dies. 1870 Napoleon declares war on Prussia. He is captured at Sedan and forced to abdicate. The Prussian army besieges Paris. 1871 France surrenders to the Prussian army and a peace treaty is signed. 1873 Alfred Jarry is born in Laval, France. 1885 A group of artists led by poet Stephane Mallarmé writes the Symbolist Manifesto. 1888 Jarry is sent to the Lycée in Rennes. Together with two classmates, Jarry writes the first version of Ubu Roi and calls it The Poles. 1887 Andre Antoine sets up the Théâtre Libre, the first theatre dedicated to naturalistic plays. 1889 The World Exhibition takes place in Paris; the Eiffel Tower is constructed for the event. 1890 Jarry moves to Paris to continue his studies but is rapidly caught up in the lively literary scene. The first performance of Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler takes place in Paris. 1893 Jarry’s mother dies after catching the flu from her son. 1894 Jarry is conscripted into the army against his will. 1895 The Lumière brothers premiere the first motion picture at a café in Paris. 1896 Jarry starts working at the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre in Paris. December: Ubu Roi opens at the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre; it closes after only one performance. 1900 The Paris Métro system opens. 1904 Jarry moves to a house in the countryside outside Paris. 1907 Jarry dies in hospital age 33 after being cared for by his sister. 1908 Ubu Roi is revived for the first time. 4 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 3. A Brief Synopsis and Background to Ubu the King In David Greig’s version, the play is set in an old person’s home. It opens with Mum and Dad Ubu arguing about whether or not Dad Ubu should kill the King of Kazakhstan and take over the throne. They throw a dinner party for their friend Captain Cacker and his merry band, a raucous affair which ends with Dad Ubu poisoning several guests by making them eat shit from a toilet brush. After the party, Dad Ubu declares his intention to make Captain Cacker Grand Duke of the Gobi desert, and Captain Cacker realises that Dad Ubu is planning to assassinate the King. Shortly thereafter, the king sends for Dad Ubu and announces that he’s making him Marquis of Mongolia. The King asks Dad Ubu to participate in a big parade the following day. Dad Ubu and Captain Cacker discuss the various ways of killing the King, and decide to perform the coup during the celebratory parade. The Queen, meanwhile, has had a terrible dream in which she sees her husband killed, and she tries to dissuade him from attending the parade. The King ignores her, and to prove he’s not afraid, he goes to the parade without both sword and armour. At the parade, Dad Ubu and Captain Cacker swiftly kill the King and Dad Ubu claims the throne. The terrified Queen and Prince Buggeroff manage to escape after a bloody fight with Dad Ubu and his men. They take refuge in a mountain cave, but the Queen is weak and soon dies. The Prince sees the spirits of his ancestors, who tell him to avenge his parents’ death. Once on the throne, Dad Ubu sets about causing havoc in the state. He hands out money and pies to the people to persuade them to pay their taxes. He kills all the rich people in his kingdom and takes their wealth and titles. He kills the judges and takes law and order into his own hands, and invents a series of new taxes which only benefit him. Together with his soldiers, he goes to the house of some poor people to collect their new tax, and when they can’t pay they are all killed and their house destroyed. Meanwhile, Captain Cacker has been thrown in the dungeon, as Dad Ubu is convinced that he doesn’t need his old friend anymore. Captain Cacker warns him to stop his savage rule to avoid the people’s revenge, but Dad Ubu dismisses his advice. Captain Cacker then phones the Russian Tsar, and asks for his help in returning the throne to its rightful owner, Prince Buggeroff. Cacker informs Dad Ubu of the Tsar’s decision to fight him. Dad Ubu is terrified of war, but Mum Ubu persuades him to go into battle. He gets prepared to go and announces that Mum Ubu will be running the country while he is at war. Mum Ubu, of course, wastes no time trying to take control herself, but before long the castle is attacked by Prince Buggeroff and Mum Ubu is forced to flee. Dad Ubu, too, is on the run, after a particularly bloody battle with the Tsar. Dad Ubu finds a dark cave to hide in. Coincidentally, Mum Ubu ends up in the same cave, at first scaring Dad Ubu by pretending to be a ghost. They begin to argue, but they’re interrupted by Prince Buggeroff who storms into the cave to fight them. After a brief struggle, Mum and Dad Ubu escape and decide to make their way back to England. 5 UBU THE KING Resource Pack The character of Ubu first appeared in a satirical sketch, written not by Alfred Jarry himself, but by two of his classmates at his school in Rennes. Henri Morin and his brother Charles had written a short play called The Poles mocking their pompous mathematics teacher, Felix Hébert. Hébert, or ‘Père Heb’, was described as an enormously fat, barrel-like figure; the very epitome of the petit bourgeois greed Alfred was growing to hate. When Jarry contributed to the play, it became increasingly wicked in its satire, and more and more bizarre. He added the concentric circles on Père Heb’s stomach, and renamed the protagonist Ubu. The Poles was performed in December 1888 at the Morins’ home, using a set of marionettes which Jarry had been given for Christmas. He was then fifteen years old. After that, Ubu continued to appear in Jarry’s writings, but it was not until after he returned from military service that he wrote the final version of Ubu Roi as it survives today. In 1896, Lugné-Poe, artistic director at the small avant-garde theatre Théâtre de l’Oeuvre, asked Jarry to come and work at various odd jobs in the theatre – helping him to plan the schedule, paint scenery and even play small parts in a few productions. Jarry soon began to press Lugné-Poe for a production of his play, saying that the play was both cheap to produce and had great commercial potential. Eventually, Lugné-Poe gave in, and the play was given its first performance on December 9th, 1896, before an invited audience of intellectuals and friends. The set had been painted by a group of men including the artists Toulouse-Lautrec and Bonnard, but the orchestra Alfred originally wanted had had to be reduced to a piano and a drum. Before the curtain went up, Alfred gave a lengthy speech in which he apologised for the poor state of the set and the fact that they hadn’t had enough rehearsal time, and described Ubu as ‘a school boy’s caricature of one of his professors who personified for him all the ugliness in the world’. Many of the audience members that night had read the play before seeing the performance, but were nonetheless shocked by the puppets, the use of masks, the explicit language and the unusual style of scenic painting. The shock at the dress rehearsal, however, was nothing compared to the absolute outrage created by the first public performance the following night. As soon as the first word was uttered – the now-famous ‘Merdre!’1 – audience members began shouting, fighting and leaving the theatre. Alfred Jarry had become a celebrity overnight, but the play was given one performance only and was not performed again until twelve years later, in 1908. Jarry, however, returned to the Ubu character several times throughout his life. In 1900, he wrote Ubu Enchâíné, which had to wait for its first performance until the Paris Exhibition in 1937. A year later, he wrote Ubu sur la Butte, and before his death also Ubu Cocu, published posthumously in 1944. 1 A conscious miss-spelling of ‘merde’, variously translated as ‘shite’ or ‘shitr’ 6 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 4. Theatre in Alfred Jarry’s Paris When Ubu Roi premiered in 1896 it caused a riot and the play was closed down after only one performance. Today, the play might not seem so shocking, but in Jarry’s Paris it was seen as scandalous. Theatre was viewed almost exclusively as entertainment for the upperand middle classes. On the whole, plays were conventional affairs, aiming to please rather than to challenge. The dominating new trend was realism – not exactly a genre that Ubu Roi fell into. The climate was anything but receptive to the kind of experimentation Jarry was attempting. The mainstream theatre existed largely as a source of after-dinner light entertainment for the Parisian bourgeoisie, who went to socialise and enjoy an evening of ‘well-made’ drama. Normally, a play would not be considered successful unless it was given at least 100 performances, and most plays were expected to run for about 300. Consequently, theatre managers were keen to produce work which they were convinced would be popular, and the margin for experimental theatre was very small indeed. The most dominant figure in the late 19th Century was the hugely successful playwright Eugène Scribe, who was the inventor of the original ‘well-made’ play. In 1836 Scribe famously described the theatre as ‘a place for relaxation and amusement, not for instruction or correction’, and this sentiment was widely accepted throughout the 19th Century. Scribe wrote over 300 plays for Parisian theatres before his death in 1861, including comedies, vaudevilles and opera libretti, and was seminal in shaping the theatrical landscape in Paris at the time of Alfred Jarry’s arrival thirty years later. On the whole, Scribe’s plays can be described as well-structured, plot-driven plays where complexity of character or argument is sacrificed to intrigue. The plays adhere to the Aristotelian ideals of unity of place and time, and deal largely with middle-class issues and problems. Scribe’s stylistic heir, Victorien Sardou, was one of the world’s most popular playwrights between 1860 and 1900. He wrote a number of extremely successful comedies, including a few for the famous actress Sarah Bernhard. Sardou’s plays have been criticised for being overly simplistic and shallow, which may explain why so few of them are performed today. Often productions were simply vehicles for great stars, and consequently artistic standards suffered. As a reaction against this style of light entertainment, French theatre of the late 19 th Century began to display a strong tendency towards realism. As early as the 1850s, directors had begun to replicate real rooms on stage to create an illusion of reality, and a corresponding acting style soon developed. Actors began to smoke on stage, to knit, eat, even perform seemingly ‘real’ blood transfusions, as in a famous 1890 production. This realist trend grew stronger for a number of reasons. Since the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859, the interest in evolutionary theory had grown rapidly. Thinkers and artists were beginning to investigate the effect of hereditary and environmental forces on the human psyche. Also, in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war, the interest in the conditions of the working classes grew, and inspired many writers, most notably Emile Zola. His novel Thérèse Raquin is widely acknowledged as beginning of the naturalist movement. In other European countries, too, the trend developed in a similar way and the various impulses began to cross-fertilise. 7 UBU THE KING Resource Pack In 1887, André Antoine, a former clerk in a gas company, set up a theatre called Théâtre Libre. It was a theatre open only to members and therefore exempt from censorship, which gave Antoine the possibility of presenting a range of new, controversial, naturalist drama. The Théâtre Libre became the first French home for plays like Ibsen’s The Wild Duck and Tolstoy’s The Power Of Darkness. Antoine strove to observe the principle of the so-called ‘fourth wall’ in his productions, designing the set with four walls and only later deciding which one to ‘remove’, and encouraging the actors to behave as if the audience wasn’t there. Naturalism was far less popular than Scribe’s style of theatre, and was therefore relegated to the fringes, but its impact on the development of European theatre since has been enormous. Fortunately for Alfred Jarry, however, there was counter-movement to the growing realistic trend. In 1885, a group of artists, writers and thinkers had issued a manifesto outlining the ideals of symbolism. They argued that there was a higher, mystical truth to existence that could not be explained by science, but which could only be expressed through symbols or myths. The principal figure for the symbolists was poet Stéphane Mallarmé, whose thoughts on drama became very influential for the movement. In terms of theatre, symbolism first came to the fore in 1890 in the shape of a small, independent theatre run by poet Paul Fort, called Théâtre d’Art. Here a large number of authors were presented, often in a shoddy style for one performance only and by amateur actors. Consequently artistic standards suffered, Fort’s efforts were received with critical hostility, and the theatre was closed down two years later. However, Fort’s work was continued at Lugné-Poe’s Théâtre de l’Oeuvre. Between 1893 and 1899, Lugné-Poe presented works by Maeterlinck, Ibsen and Hauptmann, as well as a number of French plays and Sanskrit dramas. His goal was to find an expressive theatrical style where ‘the word creates the décor’ and his simple designs were carried out by painters such as ToulouseLautrec and Bonnard. It was here that Ubu Roi premiered in 1896, and although Lugné-Poe had to close the theatre in 1899, it was reopened in 1912 and then again after World War one, and is considered one of the most important avant-garde theatres in recent French theatre history. 8 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 5. Social and Historical Context A few years before Alfred Jarry’s birth in 1873, Napoleon’s nineteen year long rule had come to an end. In 1870 he had declared war on Prussia, only to be defeated and forced to abdicate. An emergency republic, called the Third Republic, was immediately announced. Shortly thereafter, the Prussian army besieged Paris for four months before the city surrendered and the Prussian peace treaty imposed severe penalties on the French. The Third Republic, a republican parliamentary democracy, was an unstable and largely unpopular republic, and wasn’t really meant to last as long as it did (until the German invasion in 1940). There was major controversy about whether or not France should return to being a monarchy, something which was initially widely supported amongst the general population. When the various contesting political groups decided to offer the throne to Comte de Chabord, the legal but childless heir to the throne, he refused it on the basis that he didn’t want to be king of a country with the Tricolore as its flag, since it was a symbol for the French Revolution of 1789. The French, torn between their love for the flag and their desire for a monarchy, decided to establish a ‘temporary’ republic, whilst they waited for Comte de Chabord to die so that his more liberal successor could take to the throne. However, during the next few years, public opinion changed and republicanism became increasingly popular. Under the growing threat of political chaos, the idea of re-instating the monarchy was finally abandoned in 1877 and the French crown jewels were symbolically broken up and sold off in 1885. A succession of governments within the Third Republic collapsed during its sixty-odd years’ duration, and various political groups – socialists, liberals, conservatives and others – continued to jostle for power. Nonetheless, or perhaps because of this, the Third Republic saw an explosion in creative activity, which centered mainly on Paris and became known as the ‘belle époque’. In 1889 the Eiffel tower was built for the Paris Exposition and with the rise of the Impressionist movement, the birth of cinema and its reputation as a city of sin, Paris rapidly became established as ‘the place to be’. The nineties saw a range of innovations, both in arts and in science. Artists who made their debuts included the painters Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Cézanne and composers Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. The development of film by the Lumière brothers heralded a new creative industry and spread rapidly throughout Europe, with the first performance of cinematographic images outside France given in London in 1896. The end of the 19th century also heralded the invention of aspirin, the first radio transmission, and the discovery of the electron. It was no doubt, a period of intense creative activity. The bourgeoisie, however, ruled Paris. Gastronomic etiquette, for example, played a central part in Parisian socialising, and Jarry took great care in making sure that he upset the ‘common herd’, as he called them, when he dined in fine restaurants. His tricks might include ordering an entire meal back-to-front, starting with the dessert, or challenging his friends to eat gherkins soaked in absinthe until they were sick. The bourgeoisie was obsessed with its image. It was of utmost importance to be seen to do the right thing, in the right way. Elaborate systems of etiquette were developed. One favourite pastime was to stroll in the many beautifully laid out Paris gardens. The rules for 9 UBU THE KING Resource Pack greeting acquaintances were intricate and scrupulously observed and laid out in a series of guides to behaviour. ‘While strolling a gentleman should always acknowledge an That acknowledgement should be quiet and courteous for a and obnoxious. If the acquaintance is a lady, he should acknowledged him. After a brief conversation with a lady on bow then raise his hat.’ acquaintance, it’s rude not to. gentleman should not be loud bow, but only after she has the street a gentleman should The Opera was another social playground for the bourgeoisie. Few people went to actually listen to the music; spectators usually continued to gossip and chatter throughout the performance. Social status was indicated by where one sat in the auditorium. The wealthiest patrons sat in boxes, while the music lovers sat behind the orchestra. Fashion, restaurants and casinos were other ways in which the bourgeoisie could flaunt their style and class. It is easy to see how the mannerisms and affectations of this aspirational class irritated someone like Alfred Jarry, who took every opportunity to mock these poseurs. 10 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 6. Interview with the Director Dominic Hill What attracted you to the play when you first read it? I loved its outrageousness, its sense of anarchy and excess. Also, the new translation by David Greig that we are working with is wonderfully gritty and funny and rooted in the Scottish language – rather than in some artificial, slightly abstract language. What kind of preparatory work have you done for rehearsals? David and I decided early on that we wanted to set the play in an old people’s home, so I have visited some of these to get a better sense of the institution and how people operate in such environments. Could you describe a little about how you work in the rehearsal room? I think I am working differently on this play than on any other I have done. Normally I work in great detail on the text to start with, but in this case I have been interested first and foremost in how to stage the piece, particularly in relation to the concept of the production. Once I have some idea of how it will all work theatrically I will go back to the text in detail. David Greig is a wonderfully precise and detailed writer – even in a piece that seems so messy and out of control. The production needs to do justice to this text. What do you think the challenges are in directing this play? I think the actual staging of this play is the greatest challenge. The stage directions ask for hordes of armies, mass murders, ghosts, snow storms and so on. And the style, too, is very pantomimic, almost Punch & Judy-like. Finding that style is crucial – something that is funny, violent and shocking without ultimately being boring or alienating the audience. I’m also keen to create something that isn’t just a schoolboy romp, but something that has greater meaning and profundity without losing the fun and anarchy. How do you think the play can speak to an audience today? I think the play is about the use and abuse of power. In our concept for this production it is about people at the end of their lives acting out their dreams, desires and paranoias. It’s about potential and impotence. Theatre is the greatest place for exploring the imagination, the world of our desires and fears. I think Ubu does that. What do you hope the audience will get from the experience? I hope they’ll have a good time. I think the play is very funny and outrageous and I hope the audience will enjoy that. If we can be a bit shocking and at times a bit moving too, then that will be a bonus. 11 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 7. Creative team Director New Version Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Composer Choreographer Assistant Director Cast Dad Mum Cracker/Buggeroff The Chorus Dominic Hill David Greig Tom Piper Bruno Poet Paddy Cuneen Janet Smith Tim Licata Gerry Mulgrew Ann Louise Ross Emun Elliot Thane Bettany Matthew Bill Boyd Kay Gallie Pamela Kelly Ruth McGie Bill Murdoch 12 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 8. Design Images In preparation for the production the designer will create a scale model box of the set. This provides the actors with a clear sense of the set they will be performing on and is an important aid to the other members of the creative team. The model box is also used by the Production Manager and the production team to build the set. It has to be incredibly detailed and accurate as the size, shape and colour of the final set will be dictated by the model box. From the model box detailed drawings will be made and the Production Manager and his team will work out how to build the set and what materials to use. Below are photos taken from the model box designed by Tom Piper. 13 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 14 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 9. About the Young Genius Season There’s ability, there’s talent and there’s genius. When we came up with the idea for Young Genius we were faced with a huge number of questions. Everyone is born with creative abilities of various kinds. Talent, it seems to us, is the result of a relationship: between an individual and a particular parent or teacher or even an audience. What is genius? Can it be measured? Some even deny it exists. How is it that some people can ‘do it’ almost – or so it seems – without thinking and almost as soon as they begin? We wanted this season to be a celebration of that extraordinary phenomenon: artists who know at once who they are, who find their voice the moment they start to speak. We decided to focus on plays that were written before the playwright reached the age of 26. We read a great many plays and were delighted and astonished at the range and creative force leaping off the page through history. From the fifteenth century to the 1990s, from Africa to America to Europe, young, bold playwrights were making themselves heard, reinventing their craft and changing the future of theatre. Selecting six plays for production was almost impossible. The plays we’ve chosen range from Elizabethan comedy to French surrealism to modern British drama, and span more than four hundred years of playwriting. From the dawn of Elizabethan theatre, we chose Christopher Marlowe’s epic Tamburlaine The Great, a powerful story about greed and politics, adapted in a new version by David Farr. Written just twenty years later, Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle is an anarchic romp, satirical and hilarious. Then we leap ahead in time – two hundred and thirty years – to Georg Büchner’s visceral pre-modernist Woyzeck, a withering tale of poverty and madness. Sixty years on, and Alfred Jarry is causing a theatrical scandal with Ubu the King in a Paris sizzling with artistic activity, presented here in an outrageous new version by David Greig. Sixty years later, Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka writes The Lion and the Jewel, an exuberant example of ‘total theatre’ which points towards the Nobel Prize Soyinka was later to receive. Finally, we reach the present, with Sarah Kane’s radical, shocking Phaedra’s Love, a re-working of Seneca’s tragedy which has only been seen once before in this country. To match these works of young genius, we set about finding the most exciting directors and designers we could. Led by our desire to be both local and international, we gathered six creative teams from all corners of the world. Geniuses all? You decide. What we’re sure of is that these 17 full and workshop productions celebrate – across the ages – youthful ambition, provocation, experimentation, confidence and the joy of creativity. Join us. Be inspired. 15 UBU THE KING Resource Pack 10. Bibliography and Further Reading Alfred Jarry – The Man with the Axe by Nigey Lennon (Pajandrum Books, 1984) The Banquet Years: The Arts in France, 1885-1918 by Roger Shattuck (Faber & Faber, 1959) Alfred Jarry – A Critical and Biographical Study by Keith Beaumont (Leicester University Press, 1984) Alfred Jarry and his Literary Context by Ben Fisher (University College of North Wales, 1984) Alfred Jarry by Linda Klieger Stillman (Boston Twayne, 1984) Introduction to the Ubu plays by Alfred Jarry by Simon Watson Taylor (Methuen, 1968) History of the Theatre by Oscar G Brockett (Allyn and Bacon, 1995) Links http://www.milkmag.org/jarry.htm An extensive essay on Jarry’s life and work http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/ajarry.htm A biography with a list of Jarry’s works http://www.idler.co.uk/html/idols/jarry.htm An account of Jarry’s eccentric personality http://www.ralphmag.org/jarry.html Another biography http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Paris#Paris_in_the_19th_century A concise history of Paris in the nineteenth century http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Third_Republic An explanation of the Third Republic 16