PREVALENCE OF PSITTACINE CIRCOVIRUS IN ISRAEL

advertisement

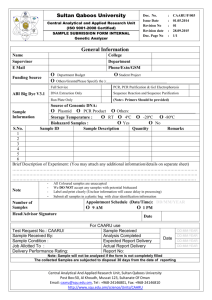

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE PREVALENCE OF PSITTACINE CIRCOVIRUS IN ISRAEL Bendheim U.1*, Karnieli A.2 , Perl S. 3 , A Lublin4 and Davidson I4. 1. The Hebrew University in Jerusalem, School of Veterinary Medicine 2. Karnieli Laboratories Ltd., Rehovot 3. Division of Pathology, Kimron Veterinary Institute, Bet Dagan 4. Division of Avian Diseases, Kimron Veterinary Institute, Bet Dagan *Corresponding author: Uri Bendheim, POB 196, Shawe Zion, Israel. dr-uri@012.net.il. Telefax + 972 4 9828246 Summary In 1981 Beak-and-Feather Disease was diagnosed in Psittacines in Australia. In 1989 a circovirus was isolated as the agent of Psittacine Beak-and-Feather Disease (PBFD). The disease was first diagnosed in Israel in 1991, based on characteristic clinical and histopathological lesions and electron microscopy. In the years 2001-2005 diagnoses was performed by means of PCR. Between the years 200±-2004 a total of 532 samples were sent to laboratories abroad, most to MDS in South Africa. 14.3% were positive for PBFD. During the first eight months of 2005 448 samples were tested by PCR in Israel, of which 26.8% were positive. The highest rate of infection, 32.17%, was found in Psittacines from Australia and South-East Asia, as compared to 10.63% for South American and 6.18% for African Psittacines. Because no treatment or vaccine exists, monitoring by PCR and removing infected birds from aviaries are of particular importance. Introduction In 1981 a clinical syndrome in Psittacines was described in Australia. The main signs of the syndrome, which had been observed already previously (1), were feather loss and feather dystrophy as well as defects in the beak (1,2,3). The syndrome was therefore given the name of “Psittacine Beak-and-Feather Disease” (PBFD). The disease causes immunodeficiency (4), severe anemia and leucopenia (5) and is the most prevalent illness among Psittacines in the wild, therefore, constitute a very real threat to endangered species in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa (6). In 1984 basophilic inclusion bodies were described in the cell nuclei and cytoplasm of sick Psittacines (Fig. 1), especially in feathers, skin, beak, the bursa of fabricii and the thymus. These cytological changes are pathognomonic, and have therefore been used ever since for verification of the diagnosis (7). In a PsCV-positive parrot (Eclectus Roratus) intranuclear inclusion bodies were observed in the esophagus (Fig. 2). In 1989 the virus was first isolated from a sick cockatoo (2,3,8), and characterized as a circovirus, Psittacine circovirus (PsCV). Circoviruses, including PsCV are highly target-specific, thus PsCV is incapable of infecting hen, pigeons or pigs, all of which have their own specific circovirus (8). The virus has two variants, PsCV1 and PsCV2; the latter causes feather dystrophy in lorries, however, unlike the case with PsCV1, birds recover from the disease (12). Recently additional variants of the virus have been reported (11,13). In 1991 the disease was first diagnosed in Israel in two cockatoos imported from Singapore (9). The diagnosis was based on typical clinical signs (Fig. 3), including typical inclusion bodies in skin and feathers, as visualized by electron microscopy (performed at the University of veterinary medicine in Vienna by Dr. Schilcher). No vaccination or efficient treatments for PBFD are presently available, and the method of choice is identification and removal of virus carriers from breeding flocks. In 1999 a PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) test for diagnosing the virus was described (10), replacing the Haemagglutination Inhibition Test (HI), that has been found to be inefficient in identifying carriers of PsCV (11). In the present study we present the PCR survey of PsCV-infected Psittacines in the years 20012004 and first 8 months of 2005. The PCR systems employed in the present study were PsCV universal, and no differentiation among PsCV variants was done. Material and Methods Tests were made from blood samples absorbed into sterile absorbent paper. The blood was taken from the wing vein (V. Ulnaris); in a number of cases feathers were sent, especially growing (blood) feathers. The samples were sent to the laboratories inside plastic envelopes or sterile test tubes. In the years 2000-2004 most of the samples were sent to MDS(A) Laboratories, directed by Dr. York, where they were tested with PCR using a method described by Ypelaar (10). Some samples were sent to Laboklin (B) in Germany, to the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Leipzig(C) or Avian Biotech (D) in England, and were tested using a similar method (10). This paper’s blood test data for 2001-2004 summarize only samples sent from the clinic of Dr. Bendheim. The data for January-September 2005 include blood samples taken by most avian veterinary physicians in Israel as well as directly by large breeders. Most of the testing was done at the Karnieli Laboratories in Rehovot (n=399). DNA samples were obtained from blood cards sent by veterinarians and birders to Karnieli Laboratories Ltd.. The DNA was isolated using “Generation DNA Purification Solution” made by Gentra (Minneapolis, MN USA). The PCR amplification was done as described (13); the primer sets used were COAF (5”TCTAACTGCSCATGCGYA-3”) (nt 1955-1973), COAR (5”TTAAGTACTGGGATTGTTRGG-3”) (nt 1236-1256). PCR cycling conditions were as follows: 2 min. denaturation step at 950 C. 35 cycles were used with the following steps:20 sec. at 940 C, 30 sec. at 600 C and 30 sec. at 720 C, followed by a final extension of 7 min. at 720 C. PCR products were examined for correct size by agarose (1.3%) gel electrophoresis in 1†TBE buffer [TBE=0.089M Tris, 0.089M boric acid, 0.002M EDTA]. The amplification was done using Ready PCR Mix Bio-Lab Israel (9597). In 2005 some of the tests were done at the Department of Avian and Fish Diseases of the Kimron Veterinary Institute (n=49). The sequence produced was checked against the entire World Gene Bank store and found to agree completely with the sequence defined for PBFDV. The PCR was performed as described in (10). Results and Discussion In the years 2001-2004 only Psittacines from my clinic were observed. A total of 532 Psittacines were tested, of which 76 (14.2%) tested positive to PBFDV; of the latter, 14 (2.6%) showed characteristic clinical symptoms. Similar findings were obtained from a group of infected cockatoos in the wild in Australia; there 6.3% showed clinical changes. The reason why the percentage there was higher than in Israel is that the virus is more prevalent among Australian Psittacines (8) whereas in Israel birds from South America and Africa were also tested. In all the clinically ill birds changes in feathering was observed (Fig. 4) (feather loss, occasionally accompanied by feather deformities and feather bleeding). Beak defects were observed only in cockatoos (Fig. 3). The appearance of red feathers on belly, back and wings was observed only in Grey Parrots (Psittacus erithacus) (Fig. 5). In the latter species the appearance of red feathers is sometimes the only clinical sign (9). PBFDV was diagnosed in 5 Grey Parrots at the age of 8-25 weeks, which as expected (15), did not show any clinical symptoms. The birds died from secondary infections , probably due to immunosupression. Following the PCR-positive birds were eradicated, no further PBFDV was diagnosed in the progeny of the same breeder. During the years in question PBFDV was diagnosed with PCR in 20 species of Psittacines and one raven. Among the Psittacines were also four budgerigars with “French molt”, all of which tested positive. In 2001 most pairs belonging to a number of breeders were tested for the purpose of locating carriers. The number of tests for that year is therefore relatively high (n=162), with a relatively low percentage of carriers found. In the years 20022004 more new acquisitions were tested, quite of a few of which had been smuggled into the country, which explains the rise in the rate of infected birds (15.2-20%). The year 2005 (data available only for January through August) saw a steep rise in the number of tests (n=448), due to the testing of birds from additional clinics and directly from breeders; again, a significant rise in the rate of infected birds occurred (26.8%). See also Table 1. The actual infection rate is probably lower, since many breeders did not destroy the infected birds but sold them, so that the same bird was tested more than once. As expected (8), the infection rate among Psittacines from Australia and SouthEast Asia was higher (32.17%) than that of Psittacines from South America (10.63%) and Africa (6.18%) (Table 2). The infection rate among cockatoos was particularly high (36.8%), especially ducorps cockatoos (Cacatua ducorpsii) (59.6%). No satisfactory explanation exists for the high infection rate among cockatoos. The reason may perhaps be that traders from other countries only acquire Psittacines that have been tested for PBFD so that traders from countries that do not insist on testing are left with birds with a particularly high infection rate; to this we must add the high rate of infection among smuggled birds, and positive birds that are resold and then tested again. Since PBFD is not a notifiable disease, there are no legal grounds for demanding that an infected bird be destroyed. In the absence of a vaccine or medication, monitoring breeding flocks and destroying the infected birds can only prevent the disease. Every Psittacine that tests positive in PCR and also has clinical signs must be destroyed. Any positive Psittacine without clinical signs must be isolated and re-tested after ninety days and destroyed if it remains positive (8) References 1. Perry R.A.: A psittacine combined beak-and-feather disease syndrome. Courses Veterinarians, Australia: 81-108, 1981. 2. Ritchie B.W., Niagro F.D. and Lukert P.D.: Characterization of a new virus from cockatoos with psittacine beak-and-feather disease. Virology 17: 183-88, 1989. 3. Ritchie B.W., Niagro F.D., Lukert P.D., Latimer K.S., Walstine L.S. and Pritchard N.: A review of psittacine beak-and-feather disease — characteristics of the PBFD virus. J. of the AAV: 143-149, 1989. 4. Fudge A.M.: Avian clinical pathology, Hematology and Chemistry in Avian Medicine and Surgery, Saunders publishing, Philadelphia, 142-157, 1997. 5. Khalesi B., Bonne N., Stewart M., Sharp M. and Raidal S.: A comparison of haemagglutination, haemagglutination inhibition and PCR for detection of PBFD virus infection and a comparison of isolates obtained from Loriids. J. of Gen. Virol. 86: 3039-3046, 2005. 6. Bendheim U. and Hochleithner M. in Bendheim U. and Davidson I.: Molecular identification and prevalence of psittacine circovirus in Israel. 8th EAAV Conference, Arles, France: 9-10, 2005. 7. Pass D.A. and Perry R.A.: The pathology of psittacine beak-and-feather disease. Aust. Vet. J. 61:69-74, 1984. 8. Ritchie B.W. in Avian Viruses: Function and Control, Wingers Publishing, Lake Worth, Florida: 223-252, 1995. 9. Grund C.H., Köhler B. and Korbel R.T.: Evaluation of various tissues for diagnosis of psittacine beak-and-feather disease (PBFD). 8th EAAV Conference, Arles, France: 249-253, 2005. 10. Ypelaar I., Bassami M.R., Wilcox G.E. and Raidal S.R.: A universal polymerase chain-reaction for the detection of psittacine beak-and-feather disease virus. Vet. Microbiol. 68:141-148, 1999. 11. Ritchie B.W.: Management of circoviruses in companion and aviary birds. Proceedings of Intl. Conf. on “Animal circoviruses and associated diseases”, Belfast, p. 25, 2005 12. Heath L., Martin D.P., Warburton, L., Perrin M., Horsfield, W., Kingsley C., Rybicki E.P. and Williamson A.L: Evidence of unique genotypes of Beak and Feather Disease Virus in South Africa. J. of Virology, p. 9277-9284, 2004. 13. de Kloet E. and de Kloet R.: Analysis of beak-and-feather disease viral genome indicates the existence of several genotypes which have a complex psittacine host specifity. Arch. Virol. 149: 2393-2412, 2004. 14. Raidal S.R., McElnea C.L., and Gross G.M: Seroprevalence of psittacine beak and feather disease in wild psittacine birds in New South Wales. Aust. Vet. J. 70:137-139, 1993. 15. Schoemaker, N.J.: Psittacine beak and feather disease in African Grey Parrots — a review and update. 4th Scientific ECAMS Meeting, Munich, pp. 1-2, 2001.