The Law on Harassment, Bullying and Dignity at work

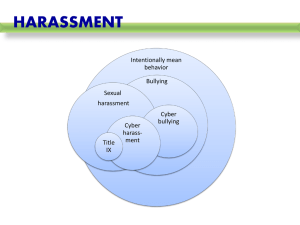

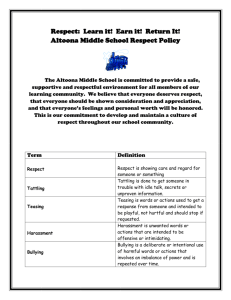

advertisement

THE LAW ON HARASSMENT, BULLYING AND DIGNITY AT WORK PAPER PRESENTED TO THE IRISH UNIVERSITIES ASSOCIATION HR CONFERENCE 2013 4th October 2013 Marguerite Bolger SC INTRODUCTION Statistics and anecdotal evidence would suggest that stress at work is as prevalent as ever, although perhaps being caused by different and more contemporary issues within a dramatically changed employment climate. Whatever the reason for the conduct which causes psychological damage to an employee, bullying, harassment and stress at work is a huge human resources issue and as a result it is a significant legal issue. In the absence of legislative intervention in the area, claims have to made within existing causes of action, most of which were never designed to deal with this difficult area. Statutory claims include harassment claims pursuant to the Employment Equality legislation, constructive unfair dismissal, claims under health and safety legislation and a newly emerging claim of penalisation under the health and safety law. legislation. Claims can also be made under the non binding Industrial Relations Personal injury proceedings are also regularly taken in the Circuit or High Court claiming negligence and breach of contract, which inevitably involves lengthy trials and substantial legal costs. There has been a spectacular lack of legislative intervention in this area. Some limited progress has been made in the Health and Safety Authority Code of Practice on Bullying and the Health and Safety Act claim of penalisation, but little or no progress has been made in establishing a statutory cause of action of bullying or harassment or even in developing a clear and satisfactory common law basis for dealing with this sensitive and difficult area of workplace relationships. The legislature has largely has left it to the Courts and lawyers to develop and apply appropriate causes of action. 1 A. 1. THE STATUTORY FRAMEWORK The Employment Equality Act 1998 - 2004 Sexual harassment and harassment on the non-gender grounds of discrimination are defined in Section 14A of the Act provides as follows:“(a) In this section – (i) References to harassment are to any form of unwanted conduct relating to any of the discriminatory grounds, and (i) References to sexual harassment are to any form of unwanted verbal, non verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature, being conduct which in either case has the purpose or effect of violating a person’s dignity and creating an intimidating, hostile, and degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for the person. (b) Without prejudice to the generality of paragraph (a), such unwanted conduct may consist of acts, requests, spoken words, gestures or the production, display or circulation of written words, pictures or other material”. The definitions do not place any limitation on the type of conduct of which an individual person might complain, although the case law suggests that the claimant must still prove on the balance of probabilities that they were subjected to conduct which is found to establish prima facia evidence of discrimination. Section 15 of the Act provides for an employer’s liability for the harassment of its employees, but permits a defence where the employer can prove that they took such steps as were “reasonably practicable” to prevent the employee’s harassment or to prevent them from being treated differently in the workplace or in the course of their employment. 2 A recent case against Eddie Rockets restaurant found in favour of two lesbian complainants who left their employment after only two weeks, due to the harassment to which they were subjected on grounds of their sexual orientation. The Equality Tribunal was very critical of the employer for not having taken reasonable steps to prevent the harassment and specifically for not having communicated a Dignity at Work policy to the employees. Another very recent case against a retail outlet, did involve the application of a Dignity at Work policy. A full investigation into allegations of verbal sexual harassment in the workplace and a sexual assault at an out of work but work related event was investigated. The supervisor against whom the allegations were made was demoted and the victim was offered a transfer to a different branch. The Tribunal was very critical of the employer for putting the onus on the victim to transfer to a different work location rather than the person who had been found guilty of harassment and awarded the maximum amount of compensation of two years remuneration. A far more positive endorsement of the approach adopted by an employer can be seen in the case of S v A Named Organisation1 where the Equality Officer praised the steps taken by the employer in dealing with a complaint of sexual harassment:“I am satisfied that the internal investigation carried out by the Investigator appointed by the Respondent was conducted in an appropriate manner. The formal process was agreed to by the parties to the complaint and the Investigator conducted his investigation to be best of his ability thereafter. In terms of a complaint of this nature the respondent organisation should have personnel who are trained in the Employment Equality Legislation and in the processes to be followed in carrying out such an investigation. Ideally two persons should conduct the investigation. There should be a formally agreed procedure for the investigation and a timeframe by which the investigation should be completed. Where possible witnesses should be consulted but the onus should be on the parties to the complaint to have these witnesses make a written statement and/or be available for questioning by the Investigators at an agreed time and venue. This would form part of the agreed process.... There should also be a mechanism for appealing the findings of an internal investigation to a more senior level appeal body in the respondent organisation”. 1 DEC-E2006-025 3 2. Constructive Dismissal under The Unfair Dismissals Act 1977 Section 1(1)(b) of the Unfair Dismissals Act 1977 provides two alternative tests for proving a constructive dismissal - that the employee was entitled to resign or that it was reasonable for the employee to resign. It is a difficult burden of proof and strong evidence of unreasonable behaviour on the part of the employer will be required. In establishing that it was reasonable to resign, it is important for a claimant to be able to show that they exhausted all internal grievance procedures that were reasonably open to them. Similar to equality law, it will also be important for an employer to demonstrate that a reasonable and accessible avenue of complaint was open to the employee. Recent case law shows quite a divergence in determining whether the conduct complained of by the employee was sufficiently serious to satisfy the onerous burden of proof to establish a constructive unfair dismissal. For example in the case of Corcoran v Embassy of the Kingdom of Lesotho the Tribunal considered the evidence and determined that the Claimant did act reasonably in resigning, having initially tried to resolve the issue with her employer. The Tribunal highlighted the employer’s failure to “engage in a meaningful way”. Compensation of over €40,000 was awarded. A recent example of where a claim for constructive dismissal was successfully defended 2 seemed to be based on the detailed and thorough investigation which had been carried out by the company’s HR manager into the employee’s very detailed grievance. The Tribunal referred to the length of time the manager had spent on the investigation and the fact that his report gave a positive response to many of the issues raised by the employee and noted that it committed the company to taking further steps. The Tribunal found that the employer had reacted fairly and thoroughly to address the employee’s concerns and therefore found that the conduct of the employer could not ground a claim for constructive dismissal. 2 UD1 587/2011 4 3. Penalisation under The Safety, Health and Welfare at Work Act 2005 Section 27 of the Health, Safety & Welfare at Work Act 2005 introduced a new concept of penalisation into the area of Health & Safety Law, defined as: “ (1) In this section "penalisation" includes any act or omission by an employer or a person acting on behalf of an employer that affects, to his or her detriment, an employee with respect to any term or condition of his or her employment. (2) Without prejudice to the generality of subsection (1), penalisation includes— (a) suspension, lay-off or dismissal (including a dismissal within the meaning of the Unfair Dismissals Acts 1977 to 2001), or the threat of suspension, lay-off or dismissal, (b) demotion or loss of opportunity for promotion, (c) transfer of duties, change of location of place of work, reduction in wages or change in working hours, (d) imposition of any discipline, reprimand or other penalty (including a financial penalty), and (e) coercion or intimidation.” Whilst the definition is quite broad, it must involve an act or omission by the employer or person acting on their behalf affecting the employee to their detriment with respect to any term or condition of their employment. The detriment suffered by employee must be as a result of certain matters set out at subsection (3) as follows: “(3) An employer shall not penalise or threaten penalisation against an employee for— (a) acting in compliance with the relevant statutory provisions, (b) performing any duty or exercising any right under the relevant statutory provisions, (c) making a complaint or representation to his or her safety representative or employer or the Authority, as regards any matter relating to safety, health or welfare at work, (d) giving evidence in proceedings in respect of the enforcement of the relevant statutory provisions, 5 (e) being a safety representative or an employee designated under section 11 or appointed under section 18 to perform functions under this Act, or (f) subject to subsection (6), in circumstances of danger which the employee reasonably believed to be serious and imminent and which he or she could not reasonably have been expected to avert, leaving (or proposing to leave) or, while the danger persisted, refusing to return to his or her place of work or any dangerous part of his or her place of work, or taking (or proposing to take) appropriate steps to protect himself or herself or other persons from the danger.” In applying Section 27, the Labour Court has made it very clear that there must be a causal connection between the conduct of the employee (most commonly the existence of a complaint under the 2005 Act) and the imposition of a detriment by the employer. For example an employer must have known of the employee’s conduct at the time the decision was made to impose the detriment on them as otherwise the employee could not have been penalised for that conduct. In Toni & Guy Blackrock Limited v Paul O’Neill3 the employee claimed his dismissal resulted from having raised certain issues relating to health and safety with his employer and with the Health & Safety Authority. The employer maintained he had been dismissed for persistent lateness and other acts of misconduct. The Court concluded that:“[T]he Claimant must establish, on the balance of probabilities, that he made complaints concerning health and safety. It is then necessary for him to show that, having regard to the circumstances of the case, it is apt to infer from subsequent events that his complaints were an operative consideration leading to his dismissal. If those limbs of the test are satisfied it is for the Respondent to satisfy the Court, on credible evidence and to the normal civil standard that the complaint relied upon did not influence the Claimant’s dismissal.” Thus, even though the Court found that there were other employment related issues with the Claimant of which the employer had “justifiable cause” to complain, the Court was satisfied that were it not for the employee’s complaints regarding health and safety, those issues would not have resulted in his dismissal. Therefore the Court found that the complaints were an operative reason for the dismissal and that his complaint of penalisation was made out. Substantial compensation of €20,000 was awarded. 3 Determination HSD 095, 18th June 2009 6 B. CIVIL PROCEEDINGS It is becoming increasing common to see stress claims being taken in the High Court (and occasionally in the Circuit Court) as a personal injuries claim. The test to establish liability was succinctly set out by Clarke J. in Maher v. Jabil Services Limited4 as follows:“(a) Has the Plaintiff suffered an injury to his or her health as opposed to what might be described as ordinary occupational stress. (b) If so, is that injury attributable to the workplace, and (c) If so, was the harm suffered to the particular employee concerned reasonably foreseeable in all the circumstances.” B(i) Establishing Bullying as an actionable wrong In Berber v Dunnes Stores5 the Supreme Court analysed the various incidents complained of to see whether, assessed objectively, the employer had taken appropriate steps to protect the employment relationship. Finnegan J. set out the following criteria of the appropriate test:“ The test is objective; 1. The test requires that the conduct of both employer and employee be considered; 2. The conduct of the parties as a whole and the cumulative effect must be looked at; 3. The conduct of the employer complained of must be unreasonable and without proper cause and its effect on the employee must be judged objectively, reasonably and sensibly in order to determine if it is such that the employee cannot be expected to put up with it” A detailed analysis of individual incidents claimed by the Plaintiff to constitute unlawful bullying and harassment was conducted by the High Court in Browne v. Minister for Justice Equality and Law Reform6. Some of the incidents were found to constitute bullying and harassment and others were not. Interestingly, the failure of the Gardai to investigate certain complaints made by the 4 [2005] 16 ELR 233 5 [2009] 20 ELR 61 6 [2013] 24 ELR 57 7 Plaintiff was not found to constitute bullying and harassment, very similar to the conclusions drawn by the same Court in the decision of Nyhan7. B(ii) Foreseeability Even where a Plaintiff establishes actionable bullying, they must also establish reasonable foreseeability on the part of the employer. In McGrath –v- Trintech Technologies Limited the plaintiff claimed he had suffered from stress as a result of the manner in which he had been treated by his employer during a placement in Uruguay. There was evidence of a number of crises having occurred during this time which he had to manage. There was evidence of an acrimonious relationship between him and his immediate boss. However Laffoy J. found that the defendant had adequately addressed any signs of vulnerability on the part of the plaintiff or possible harm to his health. She refused to impute to the defendant a knowledge of a vulnerability of which the plaintiff was aware in circumstances where the plaintiff’s psychological history and the related likelihood of psychological harm was not ascertained prior to the conduct complained of. She expressly found that there was no basis upon which the employer could not assume the plaintiff could withstand the “corporate culture” within its organisation. The plaintiff failed to cross the foreseeability threshold or to establish that the defendant had fallen below the standard to be properly expected of a reasonable and prudent employer. In her later decision in Frank Shortt –v- Royal Liver Assurance Limited8 where the plaintiff sought damages for personal injuries which he claimed he had suffered as a result of an unlawful application of the disciplinary process, Laffoy J. found that disciplinary action will almost inevitably be accompanied by a certain degree of stress but that they are events encountered in the normal course of management. In the absence of any reason to the contrary an employer is entitled to assume that an employee is entitled to withstand such stress (similar to her findings in McGrath on the “corporate culture”). In those circumstances she found that any injuries sustained by the Plaintiff were not reasonably foreseeable. The plaintiff in Maher v Jabil continued the trend of failing to establish reasonable foreseeability on the part of the employer. The plaintiff had claimed damages for stress arising from one period of 7 8 [2012] IEHC 329 [2009] 20 ELR 240 8 alleged over work and one period of alleged under work. Clarke J was satisfied from the medical evidence that the plaintiff had suffered actionable injuries caused by his work environment. In relation to the period of overwork, he concluded:“[I]t does not seem to me that, having regard to such factors as those identified in Item 5 of the practical propositions specified in Hatton, that the objective threshold for foreseeability is met. There is no evidence from which I could conclude that the work load was more than is normal in the particular job. While it may be that the work turned out to be more demanding for the plaintiff I am not satisfied that there was any evidence upon which it is reasonable to infer that the employer should have known this. It does not appear that there is any real evidence that the demands made of the plaintiff were unreasonable when compared with the demands made on others in the same or comparable jobs. Nor were there any signs that others doing the job had suffered harmful levels of stress or that there was an abnormal level of sickness or absenteeism in the same job or in the same department.” In relation to the period of underworked, Clarke J concluded:“I am not satisfied that there was any concerted plan on the part of the employer to seek to exclude the plaintiff from his employment. As also appears above I am satisfied that the plaintiff did make some complaint about the inadequacy of the work which he was been given but not as frequently or in the terms which he claims. In those circumstances I am not satisfied that the plaintiff has established a breach on the part of his employer of a duty of care during this period either.” In Berber v Dunnes Stores, Finnegan J. summarised the law on foreseeability in stress at work cases:“As to foreseeability, the issue in most cases will be whether the employer should have taken positive steps to safeguard the employee from harm and the threshold to question is whether the kind of harm sustained to the particular employee was reasonably foreseeable. The test is not concerned with the person of ordinary fortitude. The answer may be found in asking the question whether the employer knew or ought to have known of a particular vulnerability. Stress is merely a mechanism whereby harm may be caused and it is necessary to distinguish between signs of stress and signs of impending harm to health. Frequent or prolonged absences from work which are uncharacteristic for the person 9 concerned may make harm to health foreseeable: there must be good reason to think that the underlying cause is stress generated by the work situation rather than other factors. Where an employee is certified as fit for work by his medical adviser the employer will usually be entitled to take that at face value unless there is a good reason for him to think to the contrary. “ In Sweeney, the plaintiff had a history over the previous three years of absence from work due to work related stress which was found to have constituted “long and totally uncharacteristic absences from work”. Therefore the principal was found to have known or ought to have known that this “rendered the plaintiff very vulnerable to some form of mental illness such as nervous breakdown”. It was therefore reasonably foreseeable by the principal that if the plaintiff became aware of the private investigator, it was likely to be so traumatic as to “precipitate her... into mental illness”. 5. CORPORATE BULLYING AS A NEW CAUSE OF ACTION Bullying and harassment claims tend to focus on how one employee has mistreated another, frequently subordinate, employee. Whilst attempts can be made to blame the organisational as well as the individual treatment of a Plaintiff, the Kelly9 decision for the first time recognised the concept of corporate bullying in Irish law. The Plaintiff contended that she been subjected to unacceptable treatment by her line manager and that shortly after those difficulties commenced, she was systematically bullied and targeted by by management as a whole. Her allegations were numerous, involved virtually all management with whom she had dealings, sometimes extreme (including, for example, that she had been kidnapped by a manager) and were made in lengthy written complaints which clearly communicated that she was deeply unhappy with how she believed she was perceived by management and her belief this had resulted directly in unacceptable and unfair treatment of her by them and by her colleagues. The evidence in Kelly confirmed that the Plaintiff’s perception of her difficulties at work commenced after an accident she claimed occurred at work in August 2004 and caused her a injury 9 [2012] IEHC 21 10 to her back. Her line manager refused to sign her accident report form and did not report the accident in accordance with normal health and safety procedures. Shortly afterwards Ms Kelly applied for a permanent full time position which her SIPTU representative claimed should have been limited to internal candidates and that agreed procedures were breached by the appointment of external candidates. Cross J. found that the appointments were irregular and contrary to agreed procedures between management and unions and found there had been no justification given for this breach of procedure other than what he accepted was management’s the view of the Plaintiff that she was trouble and to avoid giving her a permanent position for which on the face of it she seemed entitled10. He concluded that “this amounted to corporate bullying and harassment and discrimination against the Plaintiff and resulted in stress to her”. Some months later in January 2005 the Plaintiff was suspended after she had refused to sign a statement of a complaint taken from her as she did not agree that it was accurate. Cross J. was highly critical of the suspension which he described as the Plaintiff being “frog marched off the premises which was by any scale of things an extraordinary insult to her”. He held that the suspension constituted a breach of contract, bullying and harassment and discriminatory treatment as a result of which the Plaintiff had suffered an injury and an actionable wrong. Thereafter, whilst Cross J. rejected all but one of the Plaintiff’s claims that various treatment of her constituted further bullying and harassment, he did accept that the defendants “were at this stage looking at the Plaintiff as being a ‘troublemaker’ and acted in a number of ways unfairly towards her”. Therefore what established corporate bullying was that steps taken by management were found to have been a response to their perception of the Plaintiff as a troublemaker rather than a genuine and bona fide interaction with an employee. More recently, the same Court in Browne v Minister for Justice Equality and Law Reform reiterated the status of the concept of corporate bullying. The Court found: “The Plaintiff’s case is that the bullying and harassment came not merely from fellow employees but were in fact orchestrated or directed from senior members of An Garda 10 At paragraph 5.14 11 Síochána or what is sometimes known as corporate bullying … If this Plaintiff proves a campaign by management against him then unlike most Plaintiffs in bullying cases, he does not have to establish that the activities above complained of were known by the first named defendant or the second named defendant as he is alleging that senior management were deliberately orchestrating and organising the bullying.” Whilst the Court ultimately found that the Plaintiff had been subjected to bullying including in relation to an incident which the Court found had been an attempt to punish him and undermine him in his role as a Garda, it did not make any further specific finding that the bullying to which the Plaintiff had been subjected was corporate bullying. However implicit in the judgment seems to be the finding that an organisation can be responsible as a corporate entity for the actions of more junior employees. Interestingly, in relation to one incident where the Court found that the conduct had been perpetrated probably by junior members of the force, the Court also expressly did not accept that the campaign “was necessarily orchestrated by the senior officers”. Nevertheless, it did find that the incident was aimed at undermining and demonising the Plaintiff in the eyes of his superiors and was therefore an example of bullying against him. The development of corporate bullying is a significant and novel approach in Irish law and gives rise to the possibility of bullying cases being more broadly addressed than simply relying on individual interactions between an employee and an individual manager or colleague. It will mean much more focus on organisational structures and the extent to which management had genuine reasons for how they dealt with an employee, particularly an employee who had a reputation as being difficult. It is arguable that any employee who raises any concerns about their workplace is at risk of being viewed in that light. It also raises the possibility that the more vocal an employee is about making complaints, no matter how reasonable or genuine those complaints may be, the better their chances of establishing liability against their employee for bullying and harassment as any treatment of them by management could be challenged as having been motivated even slightly by management’s perception of the individual as a difficult employee. 12 CONCLUSIONS The amount of litigation in the area of occupational stress has increased dramatically over the past ten years. Whilst the impact of Berber on establishing liability cannot be underestimated, it is a mistake to view that decision as rejecting the cause of action rather than rejecting the High Court’s conclusions on the facts that the Plaintiff had established evidence of foreseeability of his injuries and wrongful repudiation of his contract. The facts of Berber were not as strong as many facts that still arise in litigation where the cause of action that has been preserved by the Supreme Court both in Berber and in Quigley11 can still be found on the evidence and was found recently by the High Court in Sweeney12 to give rise to liability for an employer who failed to deal with a situation of serious bullying at work. It has even been expanded in Kelly to recognise the manner in which an employee can be bullied by an organisation rather than an individual within it and how that bullying treatment can continue even after the employee has left the workplace on certified sick leave. Whilst these developments present significant potential for litigation, the High Court with all of the costs, risk, publicity and stress which it inevitably involves, cannot be the right place to address the sensitive issue of workplace bullying and harassment, whether real or perceived. There must be a better way but until the legislature show some interest in this difficult area of workplace relations, it seems that lawyers will continue to have to bring an innovative approaches to how the civil Courts should address the issues that arise for an employee and their employee where allegations of workplace bullying are made. MARGUERITE BOLGER SC 11 [2008] 19 ELR 297 12 [2011] IEHC 131 13

![Bullying and Harassment Advisor role des[...]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006976953_1-320eb77689e1209d082c9ec2464350ee-300x300.png)