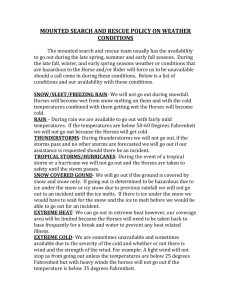

The Terminal Alfred Stieglitz 1893 (From Camera Work N° 36, 1911

advertisement

The Terminal Alfred Stieglitz 1893 (From Camera Work N° 36, 1911) Model Commentary This is a fine example of Stieglitz’s early style and his first depictions of city life in New York. Stieglitz began to photograph New York City in the 1890s and continued until the 1940s, when he abandoned photography altogether. There is a striking contrast between his early representations of the city, heavily influenced as they were by Pictorialist aesthetics, and his subsequent work, which is much more austere in nature, focusing on elevated shots of the cityscape with little if any trace of human or animal life to enliven or animate the scene. Stieglitz’s output is often divided roughly into two periods, the early, somewhat romanticised, impressionist period and the later “straight” realist photographs of the city and portraits of his wife Georgia O’Keefe. Throughout his career, Stieglitz tended to avoid the elaborate and laborious techniques employed by photographers (such as gum-bichromate printing, the coating of paper in home-made emulsions and pigments) and favoured the use of natural elements (rain, snow and steam) to create a balanced, coherent, aesthetically pleasing image. He relied heavily on the weather and random combinations of light and subject in his quest for the ideal composition. Stieglitz’s productions prior to the Great War are nevertheless markedly different in style from what they later became: The Terminal, for instance, taken shortly after Stieglitz’s return to the US, clearly appropriates a painterly façade and grammar very much in keeping with a contemporary Pictorialist style, which modelled itself to a great extent on painting in its aspiration to the status of fine art. Stieglitz’s later work departs from this vocabulary and is notable for its austere, clean lines, the careful elimination of movement (humans and animals are noticeably absent), and the unvarnished representation of form and tonal variation. Stieglitz’s later photographs of New York verge on the abstract, as they betray a preoccupation with line, shape and tone and the effects achieved through their superimposition and juxtaposition – this photograph, in contrast, is openly figurative and its subject matter fairly traditional. Stieglitz sought to capture the truth of the instant, although this could at times involve intense preparation and hours of waiting. Here we retain the impression of a moment truthfully rendered, the sense of spontaneity arising from the following: the human figure in the background apparently walking out of the frame, left; the names on the shopfront cut off (“KS & BAG”); the broom (and shovel?) resting against what appears to be a makeshift box or stand, in the middle ground to the right. This detail suggests an aesthetics of the banal or everyday which is in strong contrast to the geometric clarity, if not severity of Stieglitz’s later work, and recalls Stieglitz’s commitment to the idea of photography as ideally suited to the disclosure of the beauty and harmony latent in the most ordinary of scenes. Perhaps the most striking contrast in this photograph arises from the proximity of the powerful verticals in the background (colonnade, window, capital (chapiteau)) and the amorphous, semi-transparent, billowing clouds of steam which wrap the horses, driver and objects (broom, shovel) in a haze which increases their mystery and suggestiveness (they are not clearly or immediately perceptible). The haze suggests heat (the horses’ warm bodies and breath meeting the colder surrounding air), life and motion in contrast to the static, monumental building in the background. The photograph thus represents a streetcar and horses, the dominant element centred within the ‘frame’ formed by the building and the snow; the building providing a static backdrop that offsets the forward movement of the horses who appear through a trick of perspective to be advancing towards us, “out” of the frame, right. Snow and steam add their own poetry to the picture, which could be said to be “about” the weather and nature as much as a representation of a late 19th century street scene. Snow is here used to particular effect, as it ranges in colour from pure white to the darkest of greys. It is always an important item in Stieglitz’s pictorial lexicon, and here the snow achieves various effects: settled on ledges above and below windows, it discreetly underlines the aesthetically pleasing regularity of the architecture; heaped up in mounds to the left and right (middle ground), it gives relief and interest to what would otherwise be a flat, dull surface; turning to semi-liquid, dark-grey slush beneath the horses’ hooves, it suggests the grime and dirt of the roadway, an inevitable fact of urban life, a fact reinforced by the presence of the broom. Stieglitz harnesses the full expressive range of snow in the service of his urban aesthetics: yet here, the snow de-idealizes the cityscape, showing it to be grimy and wet – we might contrast this with other Stieglitz images such as the Flatiron Building (1903) where snow renders the cityscape delicate, mysterious and ethereal, its whiteness remaining unsullied. The title of the photograph – The Terminal – suggests this is a place where horses are fed and seen to and where they rest and return; yet the photograph communicates a sense of movement rather than stasis, with the grooves in the snow suggesting the forward motion of the streetcar, and the steam rising from the horses conveying a sense of dynamism and restlessness. We are made to see that the terminal is also where streetcars start out from, in a circular and ceaseless pattern. While the horses are foregrounded here and clearly an emblem of power and energy, the human figures are, characteristically, un-enhanced or de-emphasised. The figure in the middle-ground is slight and anecdotal, whereas the large silhouette occupying the centre of the photograph is totally concealed from our scrutiny: he turns his back to the camera (and thus to the spectator), and is clothed in a long overcoat and hat revealing no part of his anatomy. This is very much in keeping with Stieglitz’s philosophy of having the human figure blend into the cityscape as an integral part of its workings and appearance; the human figure never stands out from a given landscape, becoming its focal point; Here we have the impression that the central figure serves the animals, adjusting their harness and bridle – perhaps feeding and rubbing them down. Essentially, he is a caretaker, and portrayed as such. If the subject of the scene is a commonplace one at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, we must now consider what lends it a timeless power and significance. In terms of its composition, this photograph is very finely balanced: the backdrop of the building with its regular horizontals and verticals forms a powerful foil for the streetcar, which is at an angle to it (suggesting motion), and looks, by comparison, lightweight, frail and a little garish (the inscriptions on the roof of the car). The horses extend or ‘prolong’ the streetcar and occupy, along with the anonymous caretaker, the bulk of the picture plane. Again, balance is achieved here through the spatial proximity of caretaker and horse, the central axis of the photographic image passing somewhere between them in a very satisfying symmetry. The tonal range of the photograph is fairly extensive, between pure white and the very darkest grey. The central figures are thrown into relief through being dark against the snow, while the varying shades of snow are all, as has been suggested, in their own way expressive; the pretty white ‘edging’ to the windows, the grimy slush with its manifold prints, indicating the ceaseless motion and criss-crossing of man and animal in the city as thoroughfare. In all, a significant image dating from the early days of a prolific career, notable for its expressive tonal nuance, its sharp contrasts, its use of natural phenomena in the “rendering memorable” of an everyday street scene, its reliance on a painterly sense of ordering and perspective.