cataloging, acquisitions, serials control, conservation

advertisement

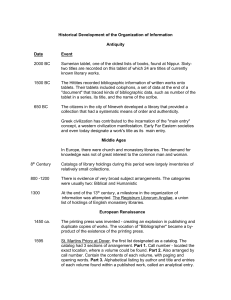

HISTORY OF BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTROL Ancient Times: Lists One of the oldest books of which we have knowledge occurs on a Sumerian tablet found at Nippur and dates about 2000 B.C. Sixty-two titles are recorded on the tablet; 24 are titles of currently known literary works Callimachus Two of the greatest libraries of antiquity, relics of Greek civilization, were at Pergamum and Alexandria. Such libraries must have had some sort of catalog, but no remnants have survived. Later writings have mentioned "Pinakes" from both, but we have no remnants or quotations from the one at Pergamum. (Pinakes is a plural of "pinax" a tablet with wax in the middle.) The Pinakes at Alexandria was compiled by Callimachus, and a few writers have quoted from them; so we have some knowledge of these lists. The work may have been a catalog, or it may have been a bibliography of Greek literature, although Callimachus is given credit as being the first cataloger of whom we have knowledge. Greeks Introduce Author Entry and the word CATALOG The most significant contribution the Greeks made to cataloging may be the use of the author of a work for its entry. There is no doubt that our whole concept of author entry first came with the Greeks; it never once appeared in any work which has survived from the earlier civilizations of the East. Even today in the Orient the traditional entry for a book is its title. The principle of author entry is a western notion and is considered to be concomitant with democracy, since it rests upon belief in the importance of the individual. The other major contribution of the Greeks is the word "catalog," made up of the Greek words "kata" meaning by, or according to, and "logos" about which there is considerable dissent, but which probably means either "word," "order," or "reason." One author (Strout) has noted that depending on the interpretation a catalog is either a work in which the contents are arranged in a reasonable way, or one in which the works are arranged according to a well-ordered plan, or merely one in which the works are arranged word-by-word. She notes that the inability to define the word itself may lie at the heart of the intellectual difficulties that have obsessed philosophers of cataloging for centuries. Middle Ages and Renaissance: Inventories Up to about the 16th century, catalogs were essentially inventories, not the sophisticated dictionary-indexes that we are accustomed to today. Toward the end of the 13th century someone whose identity is not known started a project that might be considered a milestone in the history of catalogs. This was the compilation of the Registrum Librarum Angliae, a union list of holdings of English monastery libraries in which, in a quite modern way, each library was designated by a numerical siglum. The Registrum was never finished. There are evidences of later attempts to compile continuations of it, although no finished version has survived. The 14th century brought some improvements and a few lists of this period might rightly be called shelf lists. This is also the century (the 14th) that saw the beginning of college libraries, but that did not mean any advanced contributions to the development of cataloging. The earliest lists from college libraries revert, for some reason, to the primitive inventories of the preceding centuries. This may possibly be explained by the fact that their book collections were very sparse. It was not at all unusual for a college library at this time to have fewer than 100 books. Invention of Printing 1456--Bibliographers The history of cataloging in the sixteenth century would not have much to show in the way of progress if it had been forced to depend solely upon librarians and library catalogs. Following the precedent set by Tritheim, bibliographers continued to take the lead in making improvements. One of these was Konrad Gesner of Zurich. With the publication of his author bibliography in 1545 and the subject index in 1548, a new standard of excellence was set. Enlightenment--Bodley and the Finding List At the beginning of the seventeenth century Sir Thomas Bodley offered to build up the Oxford University Library, which had been destroyed some 50 years before, and appointed Thomas James as librarian. Bodley dictated the most minute cataloging procedures (some of which James ignored). Because Bodley used the catalog in his acquisition program, he expected it to be useful. He insisted upon a classified arrangement with an alphabetical index arranged by surname. His code also called for analytical entries, and entry of noblemen under their family names. 1665--Journal des Scavans (abstract journal; first developments of scientific journals). By the beginning of the 18th century, catalogs were at last looked upon as finding lists rather than inventories. During this century they were sometimes classified an sometimes alphabetical; indexes were considered useful, although by no means necessary; some catalogs were still divided according to the size of books; authors were now always entered under surnames and were often arranged chronologically; the wording of the title page had assumed a certain degree of prestige and was now being transcribed literally and without being paraphrased (note the importance here of the development of the commercial publishing industry in accomplishing this); imprints were included. The Beginning of Codification The only noticeable innovations came from the library activities of the new republican French government. During the revolution, after the newly formed government had confiscated libraries throughout the country, it set up directions for their reorganization. In 1791 the government sent out to these libraries instructions for cataloging their collections. Here we have the first instance of a national code. Panizzi and Collocating Devices (19th century) This was a period of much argument over the relative virtues of classified and dictionary catalogs not only among librarians but among readers and scholars in general and even in reports to the House of Commons. Feelings ran very high on the subject, and rather emotional arguments were made form the statement that classified catalogs were not needed because living librarians were better than subject catalogs, to the opinion that any intelligent man who was sufficiently interested in a subject to want to consult material on it could just as well use author entries as subject, for he would, of course, know the names of all the authors who had written in his field. At the height of the frustration there appeared at the British Museum a man with strong convictions and the power to persuade. Anthony Panizzi, a lawyer by profession and a political refugee from Italy was appointed assistant librarian in 1831. In 1836 a committee was appointed by the House of Commons "to inquire into the condition, management, and affairs of the British Museum." One of the "affairs" was the state of catalogs and cataloging. During the hearings witnesses came forward in great numbers to testify for and against the current catalogs, many becoming actually vehement about this or that sort of entry. Panizzi figured prominently in the hearings and again and again was able to persuade the examiners to accept his views. In 1839 he was able to get official approval of his proposed code, and the now famous "91 rules" went into effect. Jewett Halfway through the 19th century, cataloging in the United States began to warrant attention. Up to this time, American cataloging was still following the same general pattern that had characterized European cataloging during the preceding century. For example, of the three catalogs that Harvard printed, one had been divided into three alphabets according to the size of books, all three contained the briefest of entries, and none provided subject approach. However, with Charles C. Jewett's code for the catalog of the Smithsonian Institution, published in 1850, Americans began to have influence. Jewett acknowledged his debt to Panizzi and departed in only a few instances from the precepts of the 91 rules. Jewett extended the principle of the corporate author further than Panizzi had and entered all corporate bodies directly under their names without intervening form headings. The only provision he made for subject was a reference from the subject of a biography and from any important word in the title of an anonymous work. Jewett's use of corporate entries was a departure from European practice that would not be rectified until AACR 2--though he did enter corporate bodies in direct order, that is without subdivision for subordinate bodies. Jewett also began entering pseudonymous works under the real name of the author--again a practice that would not be changed until AACR 2. Cutter When Charles Cutter published his Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalogue in 1876, he strengthened the concept that catalogs should not only point the way to an individual publication but should also assemble and organize literary units. That is, they should be collocating devices (draw things together). "In regard to the author entry it must be remembered that the object is not merely to facilitate the finding of a given book by the author's name. If this were all, it might have been better to make the entry under ... the form of name mentioned in the title, but we have also ... [that other object] to provide for [showing what the library has under a given author]." Cutter's "Objects" (really objectives or principles) have been the guiding light in the formulation of cataloging theory down to this day and are still used as the basis of attempts to quantify in a theoretical way the precepts of bibliographic control. Cutter also said that “the convenience of the public is always to be set before the ease of the cataloger. It most cases they will coincide.” CHARLES AMNI CUTTER (1876) PURPOSES OF A CATALOG 1. TO ENABLE A PERSON TO FIND A DOCUMENT OF WHICH THE AUTHOR, OR THE TITLE, OR THE SUBJECT IS KNOWN 2. TO SHOW WHAT THE LIBRARY HAS BY A GIVEN AUTHOR ON A GIVEN SUBJECT IN A GIVEN KIND OF LITERATURE 3. TO ASSIST IN THE CHOICE OF A DOCUMENT AS TO ITS EDITION AS TO ITS CHARACTER Dewey In 1900 Melvil Dewey (who by now was a leading figure in the young ALA, and head of the only library school), wrote a letter to the Library Association (Britain) suggesting that a code be adopted that would bring uniformity to the English-speaking countries. Four years of deliberations resulted in the Anglo--American code of 1908. The rules relate to the entry, heading and descriptive cataloging of works for an author and title catalog. Its importance lies in the fact of its being the first international cataloging code, and in the extent of its rapid and widespread adoption and use by all types and sizes of libraries in the two countries (remember what a successful salesman Dewey was). With some modification and amplification it continued to be used by British libraries for almost 60 years. Also published in 1908 were the Prussian Instructions in Germany. This code was representative of the codes of several European countries that differed in two fundamental ways from Anglo-American practice: 1) in non-acceptance of the principle of corporate authorship, entry being made under title when no personal author could be identified; and 2) in the grammatical arrangement of title entries as compared to Anglo-American practice of natural word arrangement. In the 1920s the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace sent four prominent American librarians to help reorganize the rich resources of the Vatican library. Out of this project grew a code that was based in part on Italian cataloging rules and in part on the AA code of 1908. The first edition was published in Italian in 1931. It was quickly accepted by catalogers in many countries as the best and most complete code then in existence. An expanded second edition was published in 1939. During the thirties and forties the Vatican code was frequently cited as the best statement of American cataloging practice, although the English translation was not available until 1948, by which time the ALA rules were about to appear. The Library of Congress began distributing printed cards to American libraries in 1901. The influence of this practice cannot be underestimated. For the first time, libraries could "buy" cataloging, without having to make any expensive effort of their own. This meant that whatever LC did was bound to become the de-facto national code in the U. S. As LC catalogers found the AA code inadequate, they issued new rules and procedures in card form, and this was the process by which rules were revised and disseminated in the U.S. Obviously, by the late 1930s it was time to develop a new AA code. LC Objectives of Descriptive Cataloging 1. To state the significant features of an item with the purpose of distinguishing it from other items and describing its scope, contents, and bibliographic relation to other items 2. To present these data in an entry that can be integrated with other entries for other items in the catalog and which will respond best to the interests of most users of the catalog. Between 1936 and 1939 both the LA and ALA cooperated in the preparation of a new joint code. The outbreak of war, however, put an end to British participation. The Catalog Code Revision Committee (CCRC) of ALA proceeded independently and produced their own preliminary second edition of the Code in 1941 in two parts: entry and heading; and description of books. The 1941 version was issued in draft form and was widely attacked on the grounds of complexity, overelaboration and too extensive use enumeration of cases. The most famous attack was that of Andrew Osborn in his article "The Crisis in Cataloging." It is one of the classic statements in cataloging theory, and certainly, one of the historical turning points in code development. Unfortunately, four decades later, some relics of his species of catalogers still survive (legalist, perfectionist, bibliographer, pragmatist): -Legalists: there must be rules and definitions to govern every point that arises -Perfectionist: guided by the compelling desire to catalog a book in all respects and in every detail -Bibliographic Cataloger: attempts to make cataloging into a branch of descriptive bibliography -Pragmatic: rules hold and decisions made to the extent that seems desirable from a practical point of view. Michael Gorman spoke of similar categories in 1981: -Decadent: alter cataloging from other libraries to suit their own sense of the fitness of things and represent the dandyish elevation of form over function -Stern mechanic: has the faith that a machine of some sort will solve our problems -Pious: cataloging is a religion with scared texts, sacred objects, a central body of doctrine and high priests -Functionalist: believes catalogs are instruments of communication; anything increasing this communication is good; anything detracting from it is bad The ALA Division of Cataloging and Classification undertook revision of part 1 (Entry and heading) of the draft code in 1946 and produced the 1949 code. The Library of Congress Rules for Descriptive Cataloging was issued also in 1949 and was substituted for part two of the ALA code. These are the widely known "red-book" and "green-book." From this point the trend in the second half of the twentieth century forks. One the one hand we have continued rapid and theoretical code-development. On the other we have the development of mechanized bibliography. Twentieth Century: Codification and Mechanization The 1949 ALA rules have numerous sections and subsections to each rule. The introduction states that the rules "are intended to represent the best of the most general current practice in cataloging ...." To many of its critics it represented a continuation of the "legalistic" trend criticized years before by Osborn. There was a contrast between the two 1949 codes: LC looked forward, and ALA looked back. Since the 1949 rules were not satisfactory, ALA in 1951 invited Seymour Lubetzky, who was on the staff of the Library of Congress, to prepare a critical study of cataloging rules. About this time there was renewed collaboration of the Americans and the British with a view to producing a second Anglo-American joint code. Early drafts of Lubetzky's principles came out against complete enumeration of "cases" in rules and pointed towards a less complex code based upon well-defined principles. This was widely welcomed and Lubetzky was appointed editor of the new code. In 1960 Lubetzky published his Code of Cataloging Rules...an Unfinished Draft. It was welcomed by progressives, but conservatives began worrying about the probable costs of the extensive changes that would be necessary if such rules were adopted. Code of Cataloging Rules (Lubetzky 1960) 1) First, to facilitate the location of a particular edition of a work, which is in the library; and 2) Second, to relate and display together the editions which a library has of a given work and the works it has of a given author. At the International Conference on Cataloging Principles (ICCP) held in Paris in 1961, a draft statement of cataloging principles based upon Lubetzky's Code of Cataloging Rules was submitted. A final version of the "Statement of Principles" was adopted and participants agreed to work in their various countries for revised rules which would be in agreement with the accepted principles. The Paris Principles, which apply only to the choice and form of headings and entry words, are important because for the first time we had multinational agreement. In the future, all cataloging developments would necessarily take place in an international context. Paris Principles (1961) The catalogue should be an efficient instrument for ascertaining 2.1 whether the library contains a particular book specified by a) its author and title, or b) if the author is not named in the book, its title alone, or c) if the author and title are inappropriate or insufficient for identification, a suitable substitute for the title; and 2.2 a) which works by a particular author and b) which editions of a particular work are in the library. Lubetzky resigned editorship to begin teaching in 1962, and C. Sumner Spalding, also of the Library of Congress, took over. He found himself in a paradoxical position of heading a committee which had won international endorsement for the soundness of Lubetzky's rules while in the United States itself, the big libraries were considering the possible cataloging revision costs with something less than enthusiasm. As a result of the thinking of these large libraries (among them LC and Columbia University) limits were set on the extent to which the Code Revision Committee could apply the Paris Principles. Finally, in 1967, two texts (one British and one North-American) were published simultaneously. This was AACR. Thus the concept of dictionary catalog as finding, collocating, and evaluating tool was firmly established. A major change in the 1967 code was based on the Paris principle that author's names should appear in the catalog in the form in which they appeared on the author's works. This was the problem that caused the battle between the CCRC and the major US research libraries. These libraries had now built massive catalogs on principles of entry established by Jewett, that the fullest form of the author's real name should be used. The prospect of changing all of these headings was daunting to say the least. CCRC won the battle but lost the war. This principle, of using the form of name found in the works, was encoded in AACR, but LC declared it would apply it only to authors whose names were not already in the catalog. This was the beginning of "superimposition" which was to cause an even greater outcry when AACR 2 was published. Superimposition meant that for any new work by an author already represented in the catalog, the old form of name would be used. Meanwhile back on the international front the International Standards for Bibliographic Description had been developed subsequent to the ICCP statement on entry and heading. ISBD was formulated by IFLA " >.. as an instrument for the international communication of bibliographic information." ISBD's objectives were to make records from different sources interchangeable, to facilitate their interpretation against language barriers, and to facilitate the conversion of such records to machine-readable form. In 1974, Chapter 6 of AACR (Description) was revised and issued as a separate in order to incorporate the ISBD. It soon became apparent that the many changes made to the rules since 1967, including the incorporation of ISBD, made it very difficult to use AACR. Code revision was again undertaken with primary objectives being to reconcile the British and North American texts, to incorporate ISBD, and (as a reflection of developing technologies) to incorporate nonbook materials into the mainstream of descriptive cataloging. Further, the committee took into consideration developments in machine processing of bibliographic records. By this time, the MARC formats had taken hold, utilities such as OCLC had begun operation, and the old code was clearly out of date. AACR 2 was published in 1978, but was not implemented by the Library of Congress and British Library until January 1981, this time because of the outcry from research libraries who had refused to accept the provisions of AACR. In fact, there was little change in principles of entry between the two codes, but the residue of superimposition was still with us. LC announced that it would close its catalogs, and begin all over with AACR 2, thus leaving the other research libraries in the lerch. Now, things are somewhat more settled. Four major national libraries, the British Library, LC, and the National Libraries of Canada and Australia, have adopted AACR2 and taken an active role in its maintenance and revision. The new edition published in 1998 is a landmark in international cooperation, and is a significantly better book. However, there has been no significant alteration of the principles embodied in AACR 2. WHY CATALOGUING CODES are important: Codes (standards) determine the structure of a database, in this case the online catalog. The structure of the catalogue ultimately determines the success of the user in retrieving information. Following a standard code allows libraries to share materials and for patrons to easily transfer their skills from one library's catalogue to another's catalogue. MECHANIZATION OF BIBLIOGRAPHY: BIBLIOGRAPHIC UTILITIES 1966-1968: Development of MARC format 1968: OCLC 1977: RLIN