The Impact of Collaborative Learning through Survivor Algebra in

advertisement

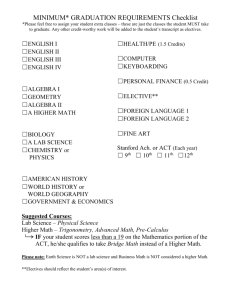

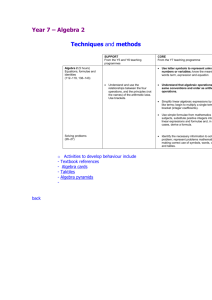

The Impact of Collaborative Learning through Survivor Algebra in the Mathematics Classroom A Capstone Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching: Mathematics Peter Wang Department of Mathematics and Computer Science College of Arts and Sciences Graduate School Minot State University Minot, North Dakota Summer 2011 ii This capstone project was submitted by Peter Wang Graduate Committee: Dr. Laurie Geller, Chairperson Mr. Timothy Morris Dr. Gary Rabe Dean of Graduate School Dr. Linda Cresap Date of defense: July 7. 2011 iii Abstract The purpose of this study was to use a collaborative learning approach through an adaptation of Karen Lyn Davis’ Survivor Algebra program to enhance student motivation and achievement in my classroom. Students from my Algebra 2 class were divided into two tribes or groups of similar abilities. For nine weeks students worked collaboratively in these groups. My expectations were for my students to become more actively involved and to achieve a higher rate of success in mathematics. Several methods of collecting and analyzing data were used to determine if expectations were met. With the aid of t-tests, grade comparisons were made between my current Algebra 2 class utilizing Survivor Algebra and my Algebra 2 class from 2009-2010. The Survivor Algebra group showed a significantly greater growth than the non-Survivor Algebra group. Pre- and postsurveys were given to gauge student feelings toward collaborative learning. After analyzing the results, I found that the overall feelings of students toward collaborative learning after using Survivor Algebra had grown more positive. Open-ended questions given at the end of each survey showed that students, for the most part, reacted positively to the use of Survivor Algebra. In my observations during the project, I found students truly enjoyed themselves. Overall, my adaptation of Survivor Algebra was not perfect, but it was definitely something I will be utilizing in the future after making a few adjustments. iv Acknowledgements I would like to initially thank Mr. Timothy Morris and Dr. Laurie Geller. As my advisor, Mr. Morris has been incredibly helpful with editing and revising my paper. He has kept me on schedule and has been willing to answer any questions regarding my paper. Along with helping in the writing of my paper, Dr. Geller has been there to encourage and has spent copious amounts of time helping me calculate and analyze the data I collected. Thank you both! Thank you to the members of my graduate committee. I appreciate your knowledgeable assistance in writing my paper. Thank you to my Master of Arts in Teaching: Mathematics classmates. Your support and help with editing have helped me make it through the process. I have learned a great deal from each of you. Finally, thank you to my friends and family for your support and encouragement. v Table of Contents Page Abstract .................................................................................................................. iii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ........................................................................................................ vii List of Figures ...................................................................................................... viii Chapter One: Introduction .......................................................................................1 Motivation for the Project ............................................................................1 Background on the Problem.........................................................................2 Statement of the Problem .............................................................................2 Statement of Purpose ...................................................................................3 Research Questions/Hypotheses ..................................................................4 Summary ......................................................................................................4 Chapter Two: Review of Literature .........................................................................5 Collaborative Learning ................................................................................7 Keys to Success............................................................................................9 Role of Teacher ..........................................................................................10 Role of Students .........................................................................................12 Summary ....................................................................................................14 Chapter Three: Research Design and Method .......................................................16 Setting ........................................................................................................16 vi Intervention/Innovation..............................................................................17 Design ........................................................................................................19 Description of Methods..............................................................................19 Expected Results ........................................................................................21 Summary ....................................................................................................22 Chapter Four: Data Analysis and Interpretation of Results ...................................23 Data Analysis .............................................................................................23 Interpretation of Results .............................................................................33 Summary ....................................................................................................37 Chapter Five: Conclusions, Action Plan, Reflections, and Recommendations .....39 Conclusions ................................................................................................39 Action Plan.................................................................................................40 Reflections and Recommendations for Teachers .......................................41 Summary ....................................................................................................42 References ..............................................................................................................44 Appendices .............................................................................................................46 Appendix A: Parental/Guardian Consent...................................................47 Appendix B: Student Assent ......................................................................50 Appendix C: Principal Consent .................................................................53 Appendix D: Survey and Open-Ended Questions .....................................55 Appendix E: Survey Results ......................................................................59 vii List of Tables Table Page 1. Descriptive Statistics for Q2 (Final) and Q2 (Test) ...................................24 2. Mean Test Score Differences and T-Test Analysis for Q2 (Survivor – Non-Survivor).........................................................................22 3. Descriptive Statistics for Diff Final = Q3 – Q2 and Diff Test = Q3 – Q2 ...................................................................................25 4. Two-Sample T-Tests to Compare Growth from Q2 to Q3 (Survivor – Non-Survivor).........................................................................25 5. Descriptive Statistics for Q3 (Final) and Q3 (Test) ...................................26 6. Two-Sample T-Tests for Q3 (Final) and Q3 (Test) (Survivor – Non-Survivor).........................................................................26 7. Pre-Survey and Post-Survey Results (Percentages) ...................................27 8. Means on Pre-Survey and Post-Survey by Question .................................28 9. Means on Pre-Survey and Post-Survey by Student ...................................29 viii List of Figures Figure Page 1. Bar chart of quarter two final and test score mean comparisons ...............34 2. Bar chart of differences in final and test score means from quarter two to quarter three comparisons ..........................................35 3. Bar chart of quarter three final and test score mean comparisons .............36 Chapter One Introduction The Internet can be a powerful tool for educators. I am constantly searching for new and exciting material to use in my classroom. It is difficult to think of teaching without the Internet as a resource. As the sole mathematics teacher in a small school located in a rural Midwest town, I am especially appreciative of the Internet. It replaces the math colleague I do not have immediately available to me. I am able to use it to extract countless excellent ideas from math teachers and other educators across the web. During one of my searches, I came across a program created by Karen Lyn Davis called Survivor Algebra. I found it to be a new and interesting way to incorporate collaborative learning into my classroom. Motivation for the Project I am currently in my sixth year as a math teacher. If there is anything I have learned throughout the years, it is that I can always improve my teaching methods. Group work has been an area I have wanted to make more of a regular practice in my classroom. I usually put students into groups for projects or activities, but this is far from a daily or even weekly occurrence. I want collaboration among my students to be more consistent and structured. 2 Background on the Problem There are days when I reflect on how the school day went, and I notice several aspects that I would like to improve. Many times I see students bored, making no attempt to get involved. This lack of interest carries over to them being unable to grasp the material and performing poorly on tests. Then there are other days when I think my lessons went well, and I noticed a common thread between these lessons which seemed to be student participation. These moments of success almost always included some group work activities. Students appeared more comfortable participating in smaller groups than in class discussion. Many times I assign each student a specific job in the group, forcing each one to get involved. These jobs range from note-taking to speaking. These observations further show me how important it is to get my students to actively participate in the classroom through group work. Statement of the Problem As an educator, I have learned how challenging it can be to increase student achievement and to keep students motivated to learn mathematics. Let me go back to my years as a student in high school and college. When I look back at the classes in which I learned the most and the ones I truly enjoyed, these classes had regular group work and student involvement. I rarely look back with fond memories of my classes where the instructor stood up in front of the room and lectured the entire time. I want to become the teacher that my students look back 3 upon with positive feelings. I want them to see I made an effort to get them motivated to learn. This reason is why I wanted to focus on using a collaborative learning approach to improve the effectiveness of my teaching. Statement of Purpose I planned to use ideas from the Survivor Algebra program to positively impact student motivation and achievement in my classroom. The goals I set for my students came directly from the Survivor Algebra User’s Manual and included the following: To build critical thinking skills To get involved in their own learning To reduce the anxiety of being in a math class and ease nerves during exams To strengthen their ability to learn math (and other things) on their own It will build the student’s confidence with math and other seemingly difficult subjects To increase exam performance and retention of material learned To provide students with a deeper understanding of the material To help students get to know their fellow students and teacher better (Davis, 2007, p. 2). 4 Research Questions/Hypotheses The main question for my research project was: Will my students’ test scores and daily work improve, and do they think using my version of Survivor Algebra was a success? I wrote a journal that detailed my daily observations of student behaviors and attitudes as well as my thoughts about implementation of Survivor Algebra and its successes and challenges. Pre- and post- surveys were given to students to acquire their opinions regarding collaborative learning and Survivor Algebra. I also compared my 2010-2011 Algebra 2 students’ grades to those from my 2009-2010 Algebra 2 class. Summary Through the use of Survivor Algebra and collaborative learning, I wanted my students to become motivated to do well, to fully understand the material I am teaching, to get involved, to improve their test performance, and to have fun in the process. This would make the overall project a success. In the following chapter, I discussed the literature I found regarding Survivor Algebra and collaborative learning. Chapter Two Review of Literature Part of reaching success in life is dependent on learning how to function in groups. Foster and Theesfeld (1993) highlighted the importance of learning how to collaborate with others: The success and progress of our society is dependent on cooperation among humans. Cooperation is very important in the daily operation of business and business organizations. Our government must cooperate with other nations. Members of sports teams must cooperate in order to be successful. Families must function in a cooperative manner in their relationships to each other. (p. 1) They also explained that individuals need to learn certain skills to be successful in collaboration, and that these abilities could be developed in the classroom. The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM, 2000) Process Standards supported this research. The Communication Standard expressed that instructional programs enable all students to: Organize and consolidate their mathematical thinking through communication Communicate their mathematical thinking coherently and clearly to peers, teachers, and others Analyze and evaluate the mathematical thinking and strategies of others; 6 Use the language of mathematics to express mathematical ideas precisely. (NCTM, Communication section) Survivor Algebra was used to teach my students these life skills along with achieving the goals listed in Chapter One. Davis (2008) cited several problems that led her to create this program. She stated that students were bored. They hated math, lacked motivation, and were not learning the material. She alluded to what happened when she switched to using Survivor Algebra as a form of collaborative learning: I really view myself more as a motivational speaker now, than as a math teacher. I used to have a very typical success rate for a community college math teacher – a very sad 40%. Yes, that’s typical…and it’s also completely unacceptable! Since I made these changes, I’ve enjoyed a very steady 75-80% success rate…for years! My students have worked very hard to earn that success…I’ve just encouraged them to do so. (p. 16) Davis outlined her typical first day school before making the change to Survivor Algebra. I’d always go through my class syllabus (which is just a bunch of rules about homework and absences) – blah blah blah…And, then, I’d give a 30 minute dissertation on the perils of cheating. In short, I was starting the semester by talking about a bunch of negative things. Start out negative…and stay negative. (p. 16) 7 She realized a change was in order. She replaced her typical first day of school with a positive approach that involved giving a speech on success. In the following sections, I discussed the definition and goals of collaborative learning and the role of the teacher and students. Collaborative Learning Collaborative and cooperative learning are the primary foci of the following studies. According to Ares (2008), collaboration is group work in which individuals work as a whole to complete a task, and cooperation is a specific type of collaboration in which the task of the group is divided up into subtasks for group members to complete. With collaborative learning, group success is determined by accomplishments as a unit. A group’s success in cooperative learning is “dependent on, and being a direct effect of, the individual work of each member of the team” (Foster & Theesfeld, 1993, p. 3). Esmonde (2009) categorized practices in her study as collaborative “when group members put their ideas together, worked together, and seemed to act as ‘critical friends’ when considering one another’s ideas” (p. 256). One specific method of using collaboration in the classroom is through collaborative test taking. Bloom (2009) studied the effectiveness of allowing students a second opportunity to take a test using collaborative group work. She found that “the second attempt not only reinforced learning through repeated exposure to course content, but it served as a review session” (p. 219). Bloom noted that test scores were much higher, and 8 students became energized during group work. Another way to look at collaboration or collaborative learning is as a form of active learning. Ueckert and Gess-Newsome (2008) described active learning as the need for students to engage with one another and the content they are studying. They also added that increasing active learning “allows students, rather than teachers, to take responsibility for the work” (p. 52). Survivor Algebra was developed as a collaborative learning program. Davis (2007) described Survivor Algebra as a program designed to get students working in groups and to develop self-learning skills. Studies support the effectiveness of using some form of collaborative learning. A study examining two high schools, one traditional and one non-traditional, showed strong evidence that the non-traditional school was “better able to serve the motivational needs of adolescent students” (Johnson, 2008, p. 69). The non-traditional school “employed group decision making, credit rather than grades, non-compulsory attendance and greater proportions of collaborative work” (Johnson, p. 69). The results showed that “schools should consider providing a variety of instructional methods with particular attention to higher proportions of collaborative learning experiences for adolescent students” (Johnson, p. 83). Another study done with college students showed that, when proper team-building was used, “students overwhelmingly reported a positive perception of their team performance and a 9 positive attitude toward academic teamwork in general” (Kapp, 2009, p. 142). The results revealed that 93% of the students shared these positive feelings. Keys to Success There are important keys to consider in making collaborative learning a success. A recurring theme from literature is that students form a sense of community with one another. In their study, Jones and Jones (2008) discussed the use of icebreakers to help students learn to “work together as a learning community” (p. 2). Ares (2008) also mentioned community along with the importance of students maintaining “responsibility, interdependence and expectations of participation” (p. 105). Hmelo-Silver and Barrows (2008) also discussed the idea of collaborative learning groups as communities and explained that “all participants must contribute” (p. 49). In a short example, Esmonde (2009) showed the significance of group practices being evenly distributed amongst students: Tony, Sarah, Mustafa, and Kendra are working together on a mathematics problem. From the teacher’s vantage point at the front of the room, they look extraordinarily productive; their heads are bent together, they are engaged in animated discussion, and Sarah’s hands gesture toward her own paper as well as Kendra’s. As the teacher circulates around the room, she pauses to observe and listen closely to the talk. Tony and Mustafa are both writing, heads down, in their notebooks. The teacher hears Sarah 10 explain her strategy for solving the problem as she gestures toward her notebook and the diagrams she has written there. She hears Kendra tell Sarah, “Oh…I get it. But I did it a different way. What do you think? I chose—” and then notices Sarah’s gaze drift back to her own paper as she begins working on the next question. (p. 250) The students were placed in a group without being given specific tasks. They were unable to benefit from the collaborative approach due to this lack of direction. Ms. Belle, a sixth-grade teacher, understood this. She subscribed to a system where she would assign students as “leaders, assistants, recorders and sergeants-at-arms for group assignments” (Ares, 2008, p. 106). Foster and Theesfeld (1993) supported the ideas that decisions on size of groups, seating arrangements, team assignments, student collaboration, lesson plans, and daily task management are crucial components in successful group work. Ciani, Summers, Easter, and Sheldon (2008) argued that when students are allowed to choose their collaborative groups they are more motivated than if the groups were chosen by the teacher. Role of Teacher “It is likely that the goal of all professors using collaborative learning as an instructional tool is to promote adaptive peer relations among students” (Ciani et al., 2008, p. 634). To attain this goal, educators must know their roles and follow several guidelines. Gaining the trust of students is vital for teachers to be 11 able to educate through collaborative learning. Davis (2007) suggested how this can be accomplished and commented that “the quickest and easiest way to build trust is to show the kids that you genuinely care about them” (p. 27). Furthermore, Davis stated the importance of getting to know the names of students to earn trust. According to Foster and Theesfeld (1993), the following teacher responsibilities are important when using collaborative learning: 1. Carefully explain the task so that each team knows its responsibilities. It may clarify the task for students if you write the instructions on the chalkboard or the overhead projector. 2. Monitor student work and behavior. 3. Answer questions only when they are team questions, and provide assistance when necessary. 4. Interrupt the group process to reinforce cooperative group skills or to provide direct instruction for all students. 5. Provide closure for the lesson. 6. Evaluate the group process by discussing the actions of team members at least twice each week. This is called processing. 7. Help students to learn to be individually accountable for learning. This should be reinforced regularly. 8. Monitor team progress and give praise when appropriate. (p. 3) 12 Brown and Renshaw (2006) found that “the conventional classroom locates teachers in privileged spaces where they can see, be seen, and influence all aspects of classroom activities” (p. 248). With this in mind, the role of the educator is changing. Teachers now assign responsibility to the students asking “what does the student need to do to learn this material” (Salter, Pang, & Sharma, 2009, p. 28). Staples (2007) summarized the teacher’s role in student collaboration with the following: “Supporting students in making contributions; establishing and monitoring a common ground; and guiding the mathematics” (p. 172). Role of Students Along with responsibilities for the teacher, Foster and Theesfeld (1993) listed the roles and responsibilities for students in collaborative learning. They stated the following: 1. Students understanding that they are part of a team and are all working toward a common goal. 2. Team members understanding that the successes or failures of the team will be shared by all members. Therefore, each member must learn to contribute as much as possible to the group goal. 3. All students learning to discuss problems with each other in order to accomplish the group goal. Contributions from each member of the team may be significant in the solution of a problem. 13 4. Team success being dependent on, and being a direct effect of, the individual work of each member of the team. 5. Learning that capitalizes on the presence of student peers, encourages interaction among students, and establishes positive relationships among team members. 6. Learning that requires the guidance of a teacher who can help students develop the cooperative learning skills they need, understand group work dynamics, and learn mathematics by working in groups. 7. Teams asking for help only after each team member has considered the question. 8. Helping students to be individually accountable for their own learning. (p. 3) According to Jones and Jones (2008), Dr. Paul Vermette concluded that a strategy to help positive relationships to occur between his students during collaborative learning “was facilitating the understanding that mutual respect and cooperation was a requirement among group members, not an option” (p. 4). Dr. Vermette created expectations for his students, and through this process “he allowed students to take ownership for their own learning experiences” (Jones & Jones, p. 8). A study by Brown and Renshaw (2006) concluded that when student participation through collaboration is used in the classroom, students “were 14 beginning to act as authors of ideas” (p. 257). Ultimately, the students were becoming active rather than passive learners. Summary Since Survivor Algebra has a collaborative learning approach, it was important to discuss what exactly is meant by collaboration. Collaboration involves working as a unit to complete the task at hand. Having a sense of community is important in successful collaborative learning. This builds trust and comfort amongst group members. The expectations and roles of the teacher and the students must also be discussed to understand if the use of Survivor Algebra can be effective in the classroom. To be effective, students must be actively involved, and the teacher must be a facilitator of events while allowing the students to be self-learners. These are the building blocks for a positive and advantageous experience for all in collaborative learning, and in this specific case, Survivor Algebra. Davis (2008) made the following conclusion about her role as a math teacher: The truth is that they will never need or use the Algebra that I am teaching and I am quite honest with them about this fact. So, why do we make all the Art and English majors take math? Because math trains them to THINK. I don’t teach “Algebra” classes, I teach classes in “Success Training.” Algebra is simply the tool I use to train my students to think 15 and to learn. Survivor Algebra builds their confidence in their ability to learn. My students won’t just fly, they’ll SOAR! (p. 31) In the following chapter, I discussed the research methods that were used to implement collaborative learning through my Survivor Algebra project. Chapter Three Research Design and Method My study involved using portions of the Survivor Algebra program to create a collaborative learning environment in my Algebra 2 classroom. I planned for this to positively impact student motivation and achievement. In this chapter, I discussed my plans for applying my adaptation of Survivor Algebra to my Algebra 2 classroom. I also described the methods used for analyzing my results. Setting My entire six-year full-time mathematics teaching career has been at my current location. There are approximately 60 students in grades 7-12. Teaching at a small school has been an excellent experience which has allowed me to become very close with my students. I view my school as an extended family, and I feel lucky to be here. Since I grew up in a small Midwest town, I believe I have an accurate perspective on what life is like for my students. I felt very comfortable using my Algebra 2 students for this study. It was a class of nine students with eight juniors and one senior. I have taught most of them since they were in the seventh grade. During this time, the students and I were able to build strong relationships with each other. In using Survivor Algebra, I split my Algebra 2 class into two groups or tribes of balanced abilities. Adjustments would have been made if I lost or gained any students, but this was not an issue. Also, I wanted this collaborative learning 17 experience to feel like something new to my students. I was hoping that even though the students knew each other well, and they were used to working together in groups, this experience could still be accomplished. I knew this could also be beneficial, since I had not planned to spend much time teaching them how to work collaboratively. Intervention/Innovation I implemented a version of Survivor Algebra in my Algebra 2 class for nine weeks. The rules I used for the project were adapted from Davis’ (2007) Survivor Algebra User’s Guide. They were as follows: 1. Students will be ranked according to their first semester grades. This ranking will be used to place the students into two tribes or groups of balanced abilities. Students will remain in the same tribe for all nine weeks. 2. Individuals may be removed from a tribe if they are disruptive. These individuals will still work in the same tribe, but they will lose all privileges that come with being in a tribe. 3. The tribes will compete in challenges (Algebra 2 tests) during the nine weeks. To win a challenge, a tribe must have the highest average challenge score. In the case of a tie, each tribe will receive the prize. 18 4. The prize for winning a challenge is one bonus point for each tribe member. The point will go toward their test grade. A winning tribe member will be excluded from the prize if his/her score is below 80%. 5. Tribes will compete collaboratively in a variety of pre-challenges (test reviews). Each member of the winning tribe will receive two bonus points that will go toward their daily grade. 6. The tribe with the most challenge and pre-challenge wins at the end of the nine weeks will receive a pizza party. 7. Individuals will remain in their tribe for any group work done throughout the nine weeks. 8. Tribal members are encouraged to interact and help each other with daily work. Successful daily work will breed success for the tribe during challenges. 9. A final challenge will be given at the end of the nine weeks. This challenge will cover material from the entire nine weeks. Any tribe member with an overall grade of 90% or above will be in the running to become the Survivor Algebra winner. The tribe member that fits this criterion, and receives the highest final challenge score, will be crowned the winner. The winner will receive two bonus points, a million dollars (ten 100 Grand bars) and a movie gift card. In the event of a tie on the final challenge, the tribe member with the highest 19 overall grade for the nine weeks will be given the win. Second and third place will be given a five dollar coupon for healthy snacks. () Design My approach for this study was mixed-methods. When I compared the grades of my current Algebra 2 class with my 2009-2010 Algebra 2 class, the study leaned toward quantitative. Students were given a survey before and after the study concerning their opinions on collaborative learning. T-tests were then used to analyze the surveys. I also kept a journal throughout the study and used my own observations for analysis. The results from my observations were dissected using a broad or qualitative path. Description of Methods The study began the first day of the second semester. It took place during the entire nine weeks of the third quarter, from January 3, 2011 to March 11, 2011. My students were informed of the purpose of the study, the duration of the study, and the methods used to collect and analyze data. The Minot State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved letters in Appendices A, B and C that were used to acquire informed consent from the students, parents, and administration. Participating students and the school maintained total confidentiality. During the course of the study, I collected three main sources of data—individual grades, survey responses, and observations. 20 At the outset of the nine weeks, the students were given a survey on collaborative learning. The survey utilized a 4-point Likert scale, which had students rate each question from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The questions were meant to gauge opinion on collaboration through group work. The survey also measured how individuals dealt with working in groups. Along with the questions that used a Likert scale, there were two open-ended questions that asked students to list their likes and dislikes about group work. Students used their prior experiences to answer the questions. I kept a journal throughout the nine weeks. I monitored student reactions and feelings during the implementation of Survivor Algebra. A close eye was kept on the level of student involvement, their confidence levels, and their overall performance in class. I was looking to determine if Survivor Algebra had a positive influence in my classroom. I used my opinions gained through observation to determine how well I believed any given situation was going. I also used the journal to document my thoughts and observations on the implementation process, including successes and challenges, changes for the future, and practices to continue. At the end of the nine weeks, students once again took the survey. This post-survey was used to determine if there was change in students’ attitudes toward collaborative learning after using Survivor Algebra. The same questions asked previously about group work were asked specifically about Survivor 21 Algebra. Students were also asked what they would change about Survivor Algebra. I did a quantitative analysis of these new results. The survey and both sets of questions are included in Appendix D. My process of data collection and analysis greatly depend on these results. The results from the Likert scale portions of the pre- and post-surveys can be found in Appendix E. The Algebra 2 grades from 2009-2010 were compared with the grades acquired during the nine week period of Survivor Algebra. I compared the growth from quarter two to quarter three in 2009-2010 to the growth over the same period during the current year. The collection of these data was no different than before my implementation of this project. Expected Results I wanted my students to come away from the study with positive attitudes toward Survivor Algebra. My hope was that no matter what their feelings were before the study, they truly learned to enjoy and appreciate collaborative learning. I believed that I would see my students become motivated to learn mathematics. I expected them to become successful group members, and I planned to see an overall increase in achievement. There were some potential obstacles that could have caused me some difficulty in completing a successful study. Students might not have taken the surveys seriously, so I could have been collecting false data. The change in student grades may have been insignificant. The tribes I formed could have made 22 for a bad mix of personalities, making for a long nine weeks. With the Algebra 2 material becoming more advanced over the course of the year, student struggles may have been incorrectly linked to Survivor Algebra. I felt I could overcome these obstacles with my understanding of mathematics and my students. Summary A modification of Survivor Algebra was used with my Algebra 2 class. The students were put into tribes, and over the course of nine weeks they worked collaboratively. The students worked together on assignments and activities, and they competed for the top group score on tests. I analyzed the use of Survivor Algebra mainly using surveys and observations. I also compared grades of last year’s non-Survivor Algebra students to this year’s Survivor Algebra students. I expected my students to become more involved in class and achieve higher success. The next chapter includes the results of the study. Chapter Four Data Analysis and Interpretation of Results For nine weeks, I incorporated a modification of the Survivor Algebra program into my Algebra 2 classroom. The purpose was to get my students motivated and to achieve a higher rate of success in mathematics. In this chapter, I will be discussing and analyzing the results I found through grade comparisons with a previous Algebra 2 class, surveys, open-ended questions, and observations. Data Analysis Survivor Algebra was used solely during the third quarter of 2010-2011. To determine if test scores and overall scores improved in my current Algebra 2 class, a comparison was made between the growth that occurred from quarter two to quarter three in 2010-2011 (Survivor group) and my Algebra 2 class from 2009-2010 (non-Survivor group). Two independent t-tests found there were no significant differences in the average end-of-quarter-two final (t = -0.90, p = 0.387) and test scores (t = -1.06, p = 0.309) of the students in the non-Survivor group and the Survivor group. Table 1 includes means, standard deviations, and sample sizes of the two groups, and Table 2 includes the t-test results. These tests indicated the groups were not significantly different based on their end-of-quartertwo final scores and test scores. This showed that there was no significant difference in the achievement levels of the two groups. 24 Table 1 Descriptive Statistics for Q2 (Final) and Q2 (Test) Q2 (Final) Group N M SD Non-Survivor 10 92.4 8.4 Survivor 8 88.4 10.3 Q2 (Test) M SD 86.56 9.97 80.8 12.5 Table 2 Mean Test Score Differences for Q2 (Survivor – Non-Survivor) Test M Diff t Q2 Final -4.0 -0.9 Q2 Test -5.76 -1.06 Note. T-tests were calculated at the 0.05 significance level. p 0.387 0.309 Since there was no significant difference in achievement levels of the nonSurvivor group of 2009-2010 and Survivor group of 2010-2011, the grades of the two groups were compared using t-tests to determine if the Survivor Algebra group from 2010-2011 learned significantly more than the non-Survivor Algebra group from 2009-2010. To do this, the following differences were calculated for both groups of students: Difference Final = Q3 Final – Q2 Final Difference Test = Q3 Test – Q2 Test The t-tests found that students in the Survivor Algebra group had significantly greater growth on their final (t = 2.04, p = 0.04) and test scores (t = 2.31, p = 0.025) from quarter two to quarter three than students in the non-Survivor 25 Algebra group. Table 3 includes means, standard deviations, and sample sizes of the two groups, and Table 4 includes the t-test results. Table 3 Descriptive Statistics for Diff Final = Q3 – Q2 and Diff Test = Q3 – Q2 Diff Final Diff Test Group N M SD M SD Non-Survivor 10 0.3 1.25 2.28 3.32 Survivor 8 4.75 6.07 9.39 8.17 Table 4 Two-Sample T-Tests to Compare Growth from Q2 to Q3 (Survivor – NonSurvivor) Test M Diff t p Diff Final 4.45 2.04 0.04* Diff Test 7.11 2.31 0.025* Note. T-tests were calculated at the 0.05 significance level. As previously stated, the tests at the beginning of the study indicated the groups were not significantly different based on their end-of-quarter-two final scores and test scores. However, in each case, the Survivor Algebra group had lower scores than the non-Survivor Algebra group (about four points lower on the final quarter two scores and about six points lower on the quarter two test scores). These averages were not significantly different, but the 2010-2011 Survivor Algebra group had more room to grow than the 2009-2010 non-Survivor Algebra group. In fact, they showed significantly more growth at the end of quarter three than the non-Survivor Algebra group. Table 5 includes means, standard deviations, and sample sizes of the two groups, and Table 6 includes the t-test 26 results. The t-tests indicate no significant differences in the average end-ofquarter-three final (t = -0.13, p = 0.9) and test (t = -0.32, p = 0.753) scores. However, the Survivor Algebra group caught and passed the average quarter three final and test scores of the non-Survivor Algebra group. The Survivor Algebra group had significantly greater growth than the non-Survivor Algebra group (see Table 4). Table 5 Descriptive Statistics for Q3 (Final) and Q3 (Test) Q3 (Final) Group N M SD Non-Survivor 10 92.7 8.17 Survivor 8 93.13 5.96 Q3 (Test) M 88.84 90.19 SD 8.94 8.77 Table 6 Two-Sample T-Tests for Q3 (Final) and Q3 (Test) (Survivor – Non-Survivor) Test M Diff t p Diff Final 0.43 0.13 0.90 Diff Test 1.35 0.32 0.753 Note. * Indicates significance at the α = 0.05 level Before the incorporation of Survivor Algebra, eight students were given a survey that asked them to rate their overall feelings toward collaborative learning using SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, and SD = Strongly Disagree. After the nine weeks of Survivor Algebra, the eight students were given the survey once again. Table 7 compares the results of the pre- and post-survey (see Appendix D). 27 Table 7 Pre-Survey and Post-Survey Results (Percentages) Pre-Survey (%) Question SA A D SD SA 1 25 25 12.5 37.5 0 2 50 25 25 0 50 3 0 25 50 25 0 4 25 37.5 25 12.5 12.5 5 75 25 0 0 37.5 6 12.5 37.5 37.5 12.5 12.5 7 0 75 25 0 25 8 50 25 25 0 50 9 37.5 37.5 25 0 37.5 10 0 0 75 25 0 11 0 25 37.5 37.5 12.5 12 0 25 50 25 0 13 25 37.5 37.5 0 37.5 14 37.5 50 12.5 0 37.5 15 12.5 50 12.5 25 37.5 16 75 25 0 0 50 Post-Survey (%) A D 25 25 25 25 25 25 62.5 12.5 62.5 0 25 50 37.5 37.5 37.5 12.5 62.5 0 0 62.5 12.5 25 12.5 50 37.5 25 50 12.5 12.5 50 50 0 SD 50 0 50 12.5 0 12.5 0 0 0 37.5 50 37.5 0 0 0 0 From Table 7, only the percentages in Questions 4, 5, 7, and 15 show a slight drop in positive feelings toward collaborative learning. Student responses to the survey were coded based on whether each question was positive or negative toward collaborative learning. Questions 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, and 16 were positive. Questions 1, 3, 6, 10, 11, and 12 were negative. The questions were scored as follows: Positive: SA = 4, A = 3, D = 2, SD = 1 Negative: SA = 1, A = 2, D = 3, SD = 4 28 The mean and standard deviation were calculated for each question on both surveys. The differences in the means from pre-survey to post-survey were also found. These results can be found in Table 8. Table 8 Means on Pre-Survey to Post-Survey by Questions Question M Pre-Survey M Post-Survey 1 2.625 3.25 2 3.25 3.25 3 3 3.25 4 2.75 2.75 5 3.75 3.375 6 2.5 2.625 7 2.75 2.875 8 3.25 3.375 9 3.125 3.375 10 3.25 3.375 11 3.125 3.125 12 3 3.25 13 2.875 3.125 14 3.25 3.25 15 2.5 2.875 16 3.75 3.5 Overall 3.047 3.164 M Difference 0.625 0 0.25 0 -0.375 0.125 0.125 0.125 0.25 0.125 0 0.25 0.25 0 0.375 -0.25 0.117 The results of the post-survey showed a positive change in how students rated 10 of the 16 survey questions. Four of the questions showed no change, and only two showed a negative change. These two questions involved getting along with other group members and motivation from rewards and extra credit. The positive ratings of 3.75 for both of these questions were high to begin with, so the 29 drop off is minimal. Question 1 rated student dislike for math, and showed the largest improvement by 0.625 on the 1-4 rating. The overall means of the ratings from the pre-survey and post-survey were 3.047 and 3.164 respectively. This shows an increase of 0.117. Means were also calculated for the pre-survey and post-survey for each individual student. As shown in Table 9, seven of the eight students that were surveyed showed improvement in their feelings toward collaborative learning. Only student D showed a decline. Table 9 Means on Pre-Survey and Post-Survey by Student Student M Pre-Survey M Post-Survey A 3.375 3.875 B 3.375 3.6875 C 2.5625 2.6875 D 3.3125 2.9375 E 3.0625 3.125 F 3.3125 3.5 G 3.125 3.1875 H 2.25 2.375 M Difference 0.5 0.3125 0.125 -0.375 0.0625 0.1875 0.0625 0.125 Following the pre-survey, students answered two open-ended questions on their feelings toward collaborative learning. After the post-survey, students answered two similar questions that were specifically about Survivor Algebra. A third question after the post-survey asked students to give more feedback 30 regarding Survivor Algebra. Below is a summary of student responses before and after the study. Pre-survey open-ended question one: Explain what you like about group work. Most students mentioned they like working with others to figure out a problem. They found it useful when able to ask peers for help and get different ideas and explanations on how to solve a problem. One student called group work fun, and another liked when he/she was able to help others that might be struggling. A couple students stated they enjoyed when group work turned competitive. Pre-survey open-ended question two: Explain what you dislike about group work. Students wrote they did not like when certain group members were “lazy” or “dead weight.” A few students noted their distaste for group members that were negative and difficult to get along with. Students also answered that they disliked group work due to fear of failing the group and getting singled out as the weak group member. A couple students said they did not like when the group rushed through an assignment and they were unable to learn anything from it. Post-survey open-ended question one: Explain what you like about Survivor Algebra. Most felt the competitive aspect (challenges, rewards, etc.) of Survivor Algebra led to motivation and improved grades. They also thought it was a fun experience. Two students pointed out that they thought the groups were 31 chosen fairly and this contributed to the success of the project. One student wrote how he/she liked the ability to ask questions in a group setting. Post-survey open-ended question two: Explain what you dislike about Survivor Algebra. Most students mentioned the reviews or pre-challenges. They feel the pre-challenges did not provide an adequate review of the material. Although most students enjoyed the pre-challenges, they felt too much time was spent playing the game and not enough examples were covered. One student did not like the pressure that came with the pre-challenges. A couple students wrote they feel some group members did not participate and were not motivated. One student had no dislikes. Post-survey open-ended question three: What would you recommend to improve Survivor Algebra? Student responses included the following: Go over more examples during pre-challenges. Add more variety to pre-challenges. Add more group activities. Reward extra credit points for highest test score. Hold Survivor Algebra competition over longer period of time. Throughout the study, I kept a journal and documented whatever I thought was relevant. As I outlined the rules of Survivor Algebra for my students, I could tell they were immediately intrigued. The idea of a competition and the opportunity to earn extra credit and prizes captured student interest. Students were 32 receptive to the idea of me choosing the tribes or groups, and reacted well when I announced them. During the pre-challenges, students were enthusiastic and competitive. In the very first pre-challenge, energy was built up to the point where the winning tribe let out a loud cheer at the point of victory. The first challenge produced the highest average the class had scored on a test all year. Students were encouraging each other during most pre-challenges, and they were not putting unfair pressure on one another to do better on the challenges. There was a high level of effort put into the pre-challenges and challenges, and most students seemed to enjoy themselves in the process. They asked me if we could continue Survivor Algebra through the fourth quarter. They also made comments that their grades might decline without the added motivation. There were moments during Survivor Algebra where students became too competitive. There was one particular moment during the second pre-challenge when there was a misunderstanding with directions. One student grew argumentative and felt he had been misled. I was able to explain how this was not true, but it was too late. The energy in the room was growing negative and tension was building. This one moment soured the whole pre-challenge. Challenge or test results were held up until all students had completed the challenge. Since the win for the tribe was dependent on their overall average, I felt it was only fair to hold test scores so there was no undue pressure put on 33 individual students. There were a few challenges where students were absent for multiple days and the rest of the class was left waiting for one student to complete the challenge. The ability for one student to hold up the results was definitely a flaw. This waiting period killed the momentum, and there were a couple of times that we had moved on to new material before students saw their results. Interpretation of Results I sought to answer the question: Will my students’ test scores and daily work improve? I found the t-tests comparing the 2010-2011 Survivor Algebra group and the 2009-2010 non-Survivor Algebra group showed the Survivor Algebra group had significantly greater growth in final and test scores from quarter two to quarter three than students in the non-Survivor Algebra group. Although the non-Survivor Algebra group improved from quarter two to quarter three, the fact that the Survivor Algebra group improved significantly greater showed me that using Survivor Algebra did improve test and daily scores. Figures 1, 2, and 3 below show where each group started, the average growth of each group, and where each group ended up. The charts visually represent how the Survivor Algebra group started lower than the non-Survivor Algebra group, but eventually caught and passed them. 34 Chart of Mean (Q2 (FINAL), Q2(TEST)) vs Year 92.40 90 88.38 86.56 80.80 80 70 Data 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Year 2009-2010 2010-2011 Q2 (FINAL) 2009-2010 2010-2011 Q2(TEST) Figure 1. Bar chart of quarter two final and test score mean comparisons. 35 Chart of Mean (Diff Final = Q3 - Q2, Diff Test = Q3 - Q2) vs Year 9.39 9 8 7 Data 6 4.75 5 4 3 2.28 2 1 0 Year 0.3 2009-2010 2010-2011 Diff Final = Q3 - Q2 2009-2010 2010-2011 Diff Test = Q3 - Q2 Figure 2. Bar chart of difference in final and test score means from quarter two to quarter three comparisons. 36 Chart of Mean (Q3 (FINAL), Q3 (TEST)) vs Year 92.70 93.13 88.84 90 90.19 80 70 Data 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Year 2009-2010 2010-2011 Q3 (FINAL) 2009-2010 2010-2011 Q3 (TEST) Figure 3. Bar chart of quarter three final and test score mean comparisons. The second question I sought to answer was the following: Do students believe using my version of Survivor Algebra was a success? The results of the pre- and post-surveys showed an overall increase of 0.117 in the mean scores. This represents that students’ overall feelings toward collaborative learning after using Survivor Algebra grew more positive. Also, seven of the eight students surveyed improved in their overall mean scores from pre-survey to post-survey. Thus, almost all of the students felt more positively toward collaborative learning after the project. I believe students had a good understanding of the questions on the surveys they were given. The increase of the total of the mean scores seems minimal, but the increase was consistent throughout. 37 In the questions following the survey, students noted that they enjoyed Survivor Algebra. They wrote that it motivated them and helped improve their test scores. Most of the negative thoughts the students had involved tweaks that could be easily made to Survivor Algebra. Overall, students reacted positively to the project. The observations I made of students during Survivor Algebra suggest that students enjoyed themselves and learned in the process. Students rarely complained and frequently made comments about how they enjoyed using the program. At times the competitive nature of the students felt like it could get out of hand, but it was usually in good fun. At the start of the fourth quarter, students asked me if we could continue using Survivor Algebra. I told them that I had already decided to stop it at the end of third quarter, but I would consider doing it over the course of the entire next year. Summary After studying the use of Survivor Algebra, I compared the grades of my 2010-2011 Survivor Algebra class to my 2009-2010 non-Survivor Algebra class. A comparison was made between the growth in each class from quarter two to quarter three. A t-test showed the Survivor Algebra group had significantly greater growth in final and test scores from quarter two to quarter three than students in the non-Survivor Algebra group. Also, the Survivor Algebra group caught and passed the mean scores of the non-Survivor Algebra group. A pre- 38 survey and a post-survey regarding collaborative leaning were given to the Survivor Algebra group before and after the study. Results from the survey showed an increase in the students’ positive feelings toward collaborative learning. Open-ended questions were given along with the surveys. Students gave mostly positive feedback about collaborative learning and Survivor Algebra. A few changes were suggested, but not many complaints were given. From my own observations, I saw students genuinely enjoying the utilization of Survivor Algebra. Competition was strong, and motivation was high. Once the competition was over, students requested to keep using Survivor Algebra. The next chapter provides conclusions, a plan of action, and reflections. Chapter Five Conclusions, Action Plan, Reflections, and Recommendations The purpose of the study was to determine if incorporating Survivor Algebra into my mathematics classroom improved student motivation and learning. The results found from grade comparisons, surveys, open-ended questions, and observations showed these improvements occurred. In the following, I will discuss these findings along with my plan of action and my recommendations for other teachers considering Survivor Algebra. Conclusions The t-tests used to compare the 2010-2011 Survivor Algebra group and the 2009-2010 non-Survivor Algebra group indicated the Survivor Algebra group had a significantly larger increase in test and daily grades from quarter two to quarter three. In fact, the Survivor Algebra group started with lower average final and test scores in quarter two than the non-Survivor Algebra group, but by the end of quarter three they had surpassed the scores of the non-Survivor Algebra group in both categories. Since Survivor Algebra was only used in quarter three, these results reinforce the success of incorporating the program. According to the surveys, positive student sentiment toward collaborative learning improved after using Survivor Algebra. Also, the open-ended questions regarding collaborative learning and Survivor Algebra indicated that, as a whole, students enjoyed using Survivor Algebra and viewed it as a worthwhile 40 experience. It was rewarding during Survivor Algebra to observe students become more actively involved and show a greater concern for their grades than I had seen all year. Action Plan I feel there was enough success with Survivor Algebra that I will use it again. My plan is to incorporate Survivor Algebra into my Algebra 2 class next year and beyond. Since I am the only math teacher at my high school, I teach the same students year after year as they work their way from seventh grade to graduation. I believe that if I was to use Survivor Algebra in all of my classes it could possibly grow stale, and lose some of its effectiveness. I am choosing to use Survivor Algebra in Algebra 2 for two reasons. First, I want to use it to help with one of the more challenging courses I teach. The second reason is that most students take Algebra 2, whereas most students do not take Advanced Math. I think it is important to get as many students involved as possible. I will make a few modifications before I use Survivor Algebra next year. I really trust the feedback I received from my students that used Survivor Algebra, and they made some quality suggestions on what I could change to improve the program. Along with making the obvious change of using Survivor Algebra over the course of an entire year, I have come up with the following list of modifications for next year: 41 Create a wider variety of pre-challenges or reviews. Concentrate on how effective they will be regarding student enjoyment and learning. Assign more collaborative group activities to build stronger unity within the tribes. Hold students accountable for their participation during group work. Next year, I plan to assign specific tasks to students during group work and prechallenges. Giving students these specified duties will heighten their responsibility within their tribes and force them to be more responsible. Reflections and Recommendations for Teachers I am pleased with the success of my Algebra 2 students after using Survivor Algebra. However, my incorporation of the program was not without imperfections. I feel that I should have used more collaborative activities along with the pre-challenges. I do not think students really felt like they were part of a tribe outside of the pre-challenges and challenges. Giving them more group activities would have helped. Also, students really enjoyed the pre-challenges, but I do not think the reviews were as effective as they could have been. If I could go back, I would have given the reviews more substance and less show. The last point I would like to make regarding what I would do differently pertains to student attitude. Students can become so competitive during competition that it may lead to negative attitudes. Next year, I am going to talk to my students beforehand about attitude and participation, and possibly give them a grade based 42 on how they behave during challenges and collaborative activities. I did not have many problems with this, but any time there was negativity it took the air out of the room. It was during the very first pre-challenge that I knew using Survivor Algebra had potential. Students acted differently during this test review than any other one all year. Having something else on the line really motivated them. I was even more encouraged seeing the results of the first test or challenge. From that point on Survivor Algebra seemed to work. I considered my 2009-2010 Algebra 2 class to be very strong, and to see the class this year come from behind and overtake them in overall grade and test scores was special to me. I recommend for any teacher thinking about incorporating Survivor Algebra to read Karen Lyn Davis’ Survivor Algebra User’s Manual. My version of Survivor Algebra is my own interpretation of her program. She shares many other thoughts and ideas, and it is all about what will work best for you as the teacher. Davis uses Survivor Algebra as a tool for training students to teach themselves. She has many interesting concepts, and it would be beneficial for teachers to see the entire scope of her program. Summary After analyzing the grade comparisons, surveys, open-ended questions, and my observations, I can say confidently that the incorporation of Survivor Algebra in my Algebra 2 class was a success. I plan to use the program with my 43 Algebra 2 class next year. This will include some changes like fine tuning prechallenges or reviews, assigning more collaborative activities, and making students more responsible. I am open to making further adaptations if I feel necessary, and am looking forward to the challenge. Once again, if you are interested in trying out Survivor Algebra, take a look at the Survivor Algebra User’s Manual and see if you feel the program is for you. 44 References Ares, N. (2008). Appropriating roles and relations of power in collaborative learning. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (QSE), 21(2), 99-121. doi: 10.1080/09518390701256472 Bloom, D. (2009). Collaborative test taking: Benefits for learning and retention. College Teaching, 57(4), 216-220. doi:10.3200/CTCH.57.4.216-220 Brown, R., & Renshaw, P. (2006). Positioning students as actors and authors: A chronotopic analysis of collaborative learning activities. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 13(3), 247-259. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca1303_6 Ciani, K., Summers, J., Easter, M., & Sheldon, K. (2008). Collaborative learning and positive experiences: Does letting students choose their own groups matter? Educational Psychology, 28(6), 627-641. doi: 10.1080/01443410 802084792 Davis, K. (2007). Survivor algebra user’s manual. Costa Mesa, CA: Coolmath.com. Esmonde, I. (2009). Mathematics learning in groups: Analyzing equity in two cooperative activity structures. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18(2), 247-284. doi: 10.1080/10508400902797958 Foster, A., & Theesfeld, C. (1993). Cooperative learning in the mathematics classroom. New York: Glencoe/McGraw-Hill. 45 Hmelo-Silver, C., & Barrows, H. (2008). Facilitating collaborative knowledge building. Cognition and Instruction, 26(1), 48-94. doi: 10.1080/07370000 701798495 Johnson, L. (2008). Relationship of instructional methods to student engagement in two public high schools. American Secondary Education, 36(2), 69-87. Jones, K., & Jones, J. (2008). A descriptive account of cooperative-learning based practice in teacher education. College Quarterly, 11(1), 1-13. Kapp, E. (2009). Improving student teamwork in a collaborative project-based course. College Teaching, 57(3), 139-143. doi: 10.3200/CTCH.57.3.139143. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics: Process standards. Retrieved June 5, 2011, from http://www.nctm.org/standards/content.aspx?id=322 Salter, D., Pang, M., & Sharma, P. (2009). Active tasks to change the use of class time within an outcomes based approach to curriculum design. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 6(1), 27-38. Staples, M. (2007). Supporting whole-class collaborative inquiry in a secondary mathematics classroom. Cognition and Instruction, 25(2-3), 161-217. doi: 10.1080/07370000701301125 Ueckert, C., & Gess-Newsome, J. (2008). Active learning strategies. Science Teacher, 75(9), 47-52. doi: 10.2505/3/tst08_075_09 Appendices 47 Appendix A Parental/Guardian Consent The Impact of Collaborative Learning through Survivor Algebra in the Mathematics Classroom Invitation to participate: Your child is invited to participate in a study of the use of a structured collaborative learning approach. The study will examine how the implementation of the Survivor Algebra program impacts student motivation and achievement. It will also compare student opinions toward collaborative learning before and after using Survivor Algebra. This study is being conducted by Peter Wang, mathematics instructor at Fairmount Public School, and a graduate student at Minot State University. Basis for Subject Selection: Your child has been selected because he/she is in Mr. Wang’s Algebra 2 class. Your child’s class was chosen because the class size and age level are appropriate for the study. If everyone agrees to participate there will be nine students who meet the criteria for the study. Overall Purpose of Study: The purpose of this paper is to help me improve my teaching methods by using a structured collaborative learning approach. The main goal of utilizing Survivor Algebra is to determine if it will have a positive effect on my students and their learning and enjoyment of math. Explanation of Procedures: If you decide to allow your child to participate, he/she will be asked to do the following: a. Work in the same group during classroom activities and test reviews for nine weeks. b. Take tests that could have a positive impact on the entire group. The tests are scored individually, but the individuals in the group with the highest average test score will receive a bonus point. This is considered winning a challenge. c. Take two surveys and answer four open-ended questions about his/her opinions on collaborative learning and Survivor Algebra. 48 The identity of all participants will remain confidential. All research will be done in the classroom. The implementations will occur during the nine weeks of the third quarter. Potential Benefits: Each participant will learn collaborative strategies that will hopefully carry over to real world situations. My goal is for students to become motivated to do well, to better understand the material I am teaching, to get involved, to improve their test performance, and to have fun in the process. Alternatives to Participation: If you decide to not allow your child to participate, he/she will still take the same tests during class, but will not be required to take the two surveys and answer the four questions. Their test scores will not be factored in for the group average, and I will not collect data from my observations of their group work. Compensation for Participation: Bonus points will be awarded to individuals if their group wins a challenge. Bonus points will also be given when a group wins a test review, which is called a pre-challenge. At the end of the nine weeks, a final challenge will be given. Students receiving the top three scores on the final challenge will all earn prizes. Assurance of Confidentiality: The identity of all participants and their data will remain confidential and stored in a locked file cabinet or on a password-protected computer. Any data collected will not be linked to the participants or the school district in any way. Following the study and completion of my master’s degree, all data will be destroyed. Withdrawal from the Study: Your child’s participation is voluntary. Your decision whether or not to allow your child to participate will not affect his/her grade. If you decide to allow your child’s participation in the study, you are free to withdraw your consent and discontinue participation at any time. You should feel free to ask questions now or at any time during the study. If you have questions or wish to withdraw your child from the study, you can contact Peter Wang at 701-474-5469 or peter.a.wang@sendit.nodak.edu. If you have questions about the rights of research subjects, contact the Chairperson of the MSU Institutional Review Board (IRB), Brent Askvig at 701-858-3052 or Brent.Askvig@minotstateu.edu. 49 Consent Statement: You are voluntarily making a decision whether or not to allow your child or legal ward to participate. You signature indicates that, having read and understood the information provided above, you have decided to permit your child or legal ward to participate. You will be given a copy of this consent from to keep. ____________________ Participant (please print student name) ____________________ ___________ _________ Signature of Parent or Guardian Relationship to subject Date ____________________ _________ Researcher’s Signature Date 50 Appendix B Student Assent The Impact of Collaborative Learning through Survivor Algebra in the Mathematics Classroom Invitation to participate: You are invited to participate in a study of the use of a structured group learning approach. The study will examine how the implementation of the Survivor Algebra program impacts student motivation and achievement. It will also compare student opinions toward group learning before and after using Survivor Algebra. This study is being conducted by Mr. Wang, mathematic instructor at Fairmount Public School, and a graduate student at Minot State University. Basis for Subject Selection: You have been selected because you are in Mr. Wang’s Algebra 2 class. Your class was chosen because the class size and age level are appropriate for the study. Overall Purpose of Study: The purpose of this paper is to help me improve my teaching methods by using a group learning approach. The main goal of using Survivor Algebra is to determine if it will have a positive effect on you and your learning and enjoyment of math.. Explanation of Procedures: If you decide to participate, you will be asked to do the following: a. Work in the same group during classroom activities and test reviews for nine weeks. b. Take tests that could have a positive impact on the entire group. The tests are scored individually, but the individuals in the group with the highest average test score will receive a bonus point. This is considered winning a challenge. c. Take two surveys and answer four open-ended questions about your opinions on collaborative learning and Survivor Algebra. The identity of all participants will remain confidential. All research will be done in the classroom. The implementations will occur during the nine weeks of the third quarter. 51 Potential Benefits: Each participant will learn collaborative strategies that will hopefully carry over to real world situations. My goal is for students to become motivated to do well, to better understand the material I am teaching, to get involved, to improve their test performance, and to have fun in the process. Alternatives to Participation: If you decide not to participate, you will still take the same tests during class, but will not be required to take the two surveys and answer the four questions. Your test scores will not be factored in for the group average, and I will not collect data from my observations of your group work. Compensation for Participation: Bonus points will be awarded to individuals if their group wins a challenge. Bonus points will also be given when a group wins a test review, which is called a pre-challenge. At the end of the nine weeks, a final challenge will be given. Students receiving the top three scores on the final challenge will all earn prizes. Assurance of Confidentiality: The identity of all participants and their data will remain confidential and stored in a locked file cabinet or on a password-protected computer. Any data collected will not be linked to the participants or the school district in any way. Following the study and completion of my master’s degree, all data will be destroyed. Withdrawal from the Study: Your participation is voluntary. Your decision whether or not to participate will not affect your grade. If you decide to participate in the study, you are free to discontinue participation at any time. You should feel free to ask questions now or at any time during the study. If you have questions or wish to discontinue participation in the study, you can contact Peter Wang at 701-474-5469 or peter.a.wang@sendit.nodak.edu. If you have questions about the rights of research subjects, contact the Chairperson of the MSU Institutional Review Board (IRB), Brent Askvig at 701-858-3052 or Brent.Askvig@minotstateu.edu. 52 Student Assent: You are voluntarily making a decision whether or not to participate. Your signature indicates that, having read and understood the information provided above, you have decided to participate. You will be given a copy of this assent form to keep. ____________________ Participant (please print student name) ______________________ _________ Signature of Participant Date _______________________ _________ Researcher’s Signature Date 53 Appendix C Principal Consent Fairmount Public School PO Box 228 Fairmount, ND 58030 Dear Mr. Townsend: I am completing work toward the Master of Arts in Teaching: Mathematics degree through Minot State University. As a degree requirement, I need to conduct a research project in my classroom during the third quarter of this year. I will examine how the implementation of the Survivor Algebra program impacts student motivation and achievement. I will also compare student opinions toward collaborative learning before and after using Survivor Algebra. To accomplish this I would like to use my adaptation of the Survivor Algebra program with my Algebra 2 class. Each student would be asked to complete a survey and answer open-ended questions regarding their attitudes toward collaborative learning and Survivor Algebra before and after the nine-week implementation. I will also be taking notes on my own observations. Survey responses, observations and test scores will be analyzed and the results will be included in my paper; however, no individual participants will be identified by name. Standard classroom confidentiality will be observed regarding all data collected. I will ask each participant to include their name on all surveys for the purpose of comparing the results, but be assured that a student’s responses will in no way impact his or her grade in my class. I have prepared letters requesting parental consent and student assent for participation in my study. Copies of these letters are attached for your inspection. I am requesting that you permit me to carry out this research in my classroom. Please contact me at peter.a.wang@sendit.nodak.edu or 701-474-5469 if you have any questions. Thank you for your consideration. 54 Sincerely, Peter Wang ______Permission for Peter Wang to conduct research in his classroom is granted. ______Permission to conduct this study is denied. Signature____________________________________________ Date__________ Mr. Jay Townsend Fairmount Public School Principal 55 Appendix D Survey and Open-Ended Questions Collaborative Learning Pre-Survey: SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, SD = Strongly Disagree Question 1. I dislike math. 2. I enjoy working collaboratively in groups with other students. 3. Working collaboratively in groups has not helped me better learn the material. 4. I prefer classes that regularly use collaborative group work. 5. I generally get along with other group members. 6. I do better when I work alone. 7. My critical thinking skills have improved from group work. 8. I am motivated by competing with other students. 9. I prefer when groups are chosen at random. 10. Overall, my collaborative group learning experiences have been negative. 11. I have difficulty communicating my thoughts when working in groups. 12. I rarely take a leadership role when working in groups. 13. I prefer to get help with homework from peers rather than a teacher. 14. I feel group work helps me build stronger relationships with my classmates. 15. I get more involved during group work than regular classroom discussion. 16. I am motivated by opportunities for rewards and extra credit. SA A D SD 56 Open-Ended Questions (Pre-Survey): 1. Explain what you like about group work. 2. Explain what you dislike about group work. 57 Collaborative Learning Post-Survey: SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, SD = Strongly Disagree Question 1. I dislike math. 2. I enjoy working collaboratively in groups with other students. 3. Working collaboratively in groups has not helped me better learn the material. 4. I prefer classes that regularly use collaborative group work. 5. I generally get along with other group members. 6. I do better when I work alone. 7. My critical thinking skills have improved from group work. 8. I am motivated by competing with other students. 9. I prefer when groups are chosen at random. 10. Overall, my collaborative group learning experiences have been negative. 11. I have difficulty communicating my thoughts when working in groups. 12. I rarely take a leadership role when working in groups. 13. I prefer to get help with homework from peers rather than a teacher. 14. I feel group work helps me build stronger relationships with my classmates. 15. I get more involved during group work than regular classroom discussion. 16. I am motivated by opportunities for rewards and extra credit. SA A D SD 58 Open-Ended Questions (Post-Survey): 1. Explain what you like about Survivor Algebra. 2. Explain what you dislike about Survivor Algebra. 3. What would you recommend to improve Survivor Algebra? 59 Appendix E Survey Results Pre-Survey Results: SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, SD = Strongly Disagree Question SA A 2 2 D 1 SD 3 2. I enjoy working collaboratively in groups with other students. 3. Working collaboratively in groups has not helped me better learn the material. 4. I prefer classes that regularly use collaborative group work. 5. I generally get along with other group members. 4 2 2 0 0 2 4 2 2 3 2 1 6 2 0 0 6. I do better when I work alone. 1 3 3 1 7. My critical thinking skills have improved from group work. 8. I am motivated by competing with other students. 0 6 2 0 4 2 2 0 9. I prefer when groups are chosen at random. 3 3 2 0 10. Overall, my collaborative group learning experiences have been negative. 11. I have difficulty communicating my thoughts when working in groups. 12. I rarely take a leadership role when working in groups. 0 0 6 2 0 2 3 3 0 2 4 2 13. I prefer to get help with homework from peers rather than a teacher. 14. I feel group work helps me build stronger relationships with my classmates. 15. I get more involved during group work than regular classroom discussion. 16. I am motivated by opportunities for rewards and extra credit. 2 3 3 0 3 4 1 0 1 4 1 2 6 2 0 0 1. I dislike math. 60 Post-Survey Results: SA = Strongly Agree, A = Agree, D = Disagree, SD = Strongly Disagree Question SA A 0 2 D 2 SD 4 2. I enjoy working collaboratively in groups with other students. 3. Working collaboratively in groups has not helped me better learn the material. 4. I prefer classes that regularly use collaborative group work. 5. I generally get along with other group members. 4 2 2 0 0 2 2 4 1 5 1 1 3 5 0 0 6. I do better when I work alone. 1 2 4 1 7. My critical thinking skills have improved from group work. 8. I am motivated by competing with other students. 2 3 3 0 4 3 1 0 9. I prefer when groups are chosen at random. 3 5 0 0 10. Overall, my collaborative group learning experiences have been negative. 11. I have difficulty communicating my thoughts when working in groups. 12. I rarely take a leadership role when working in groups. 0 0 5 3 1 1 2 4 0 1 4 3 13. I prefer to get help with homework from peers rather than a teacher. 14. I feel group work helps me build stronger relationships with my classmates. 15. I get more involved during group work than regular classroom discussion. 16. I am motivated by opportunities for rewards and extra credit. 3 3 2 0 3 4 1 0 3 1 4 0 4 4 0 0 1. I dislike math.