Joseph F - Georgetown Digital Commons

advertisement

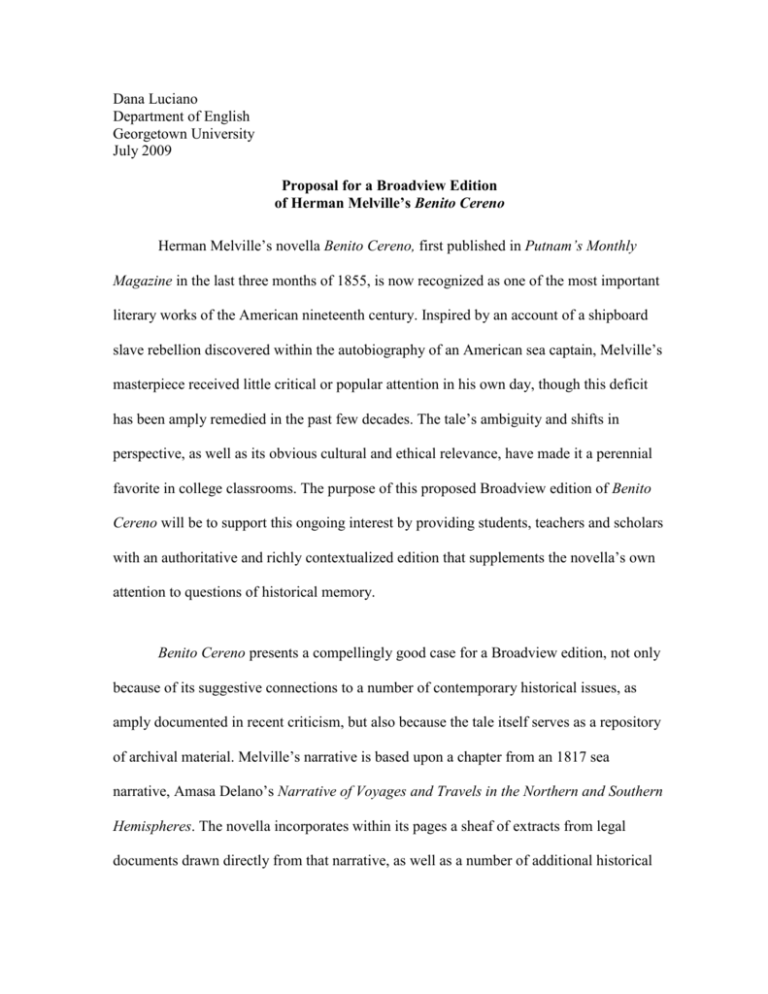

Dana Luciano Department of English Georgetown University July 2009 Proposal for a Broadview Edition of Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno Herman Melville’s novella Benito Cereno, first published in Putnam’s Monthly Magazine in the last three months of 1855, is now recognized as one of the most important literary works of the American nineteenth century. Inspired by an account of a shipboard slave rebellion discovered within the autobiography of an American sea captain, Melville’s masterpiece received little critical or popular attention in his own day, though this deficit has been amply remedied in the past few decades. The tale’s ambiguity and shifts in perspective, as well as its obvious cultural and ethical relevance, have made it a perennial favorite in college classrooms. The purpose of this proposed Broadview edition of Benito Cereno will be to support this ongoing interest by providing students, teachers and scholars with an authoritative and richly contextualized edition that supplements the novella’s own attention to questions of historical memory. Benito Cereno presents a compellingly good case for a Broadview edition, not only because of its suggestive connections to a number of contemporary historical issues, as amply documented in recent criticism, but also because the tale itself serves as a repository of archival material. Melville’s narrative is based upon a chapter from an 1817 sea narrative, Amasa Delano’s Narrative of Voyages and Travels in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. The novella incorporates within its pages a sheaf of extracts from legal documents drawn directly from that narrative, as well as a number of additional historical 2 allusions and emendations. Building upon these layers of history, the novella implicitly challenges the reader with questions of historical and contextual interpretation. The crux of the tale is Captain Delano’s initial failure to recognize the slave rebellion that has taken place aboard the Spanish ship he believes to be captained by Don Benito Cereno, an interpretive failure that results, in part, from the limits of Delano’s knowledge and experience. Melville’s narrative technique at once aligns the reader with Delano’s limited perspective while encouraging him or her, by means of these historical allusions and other clues, to look beyond that perspective, foregrounding both the difficulty and the necessity of historically informed interpretation. Scholarly takes on Benito Cereno in the past three decades have highlighted the extent to which the novella is, as H. Bruce Franklin puts it, “thoroughly and dynamically infused with history.” Certainly there has been no shortage of work detailing the novella’s connection to the pressing concerns of Melville’s day: most notably the transatlantic slave trade and resulting debates over the practice of slavery, but also the legacy of European colonialism and the push for American expansionism. Running alongside these has been a thread of inquiry into the ways the text engages not only the content but also the form of history. These critical traditions, taken together, implicitly point toward the set of questions dominating contemporary developments in Americanist literary scholarship overall: how to reframe American literary history in ways less bounded by conventional constructions of time and space, period and nation. This new scholarly interest in the transnational and transhistorical implications of literary works, evidenced by recent special issues of journals such as PMLA, American Literary History, ESQ and American Literature, is central to my proposed Broadview edition of the work, which foregrounds 3 both the transnational dimensions of the novella and its dynamic relationship to history. In addition to an annotated edition of the story, critical introduction, chronology, and extensive bibliography, this edition will contain primary source materials selected and arranged to support a number of critical and pedagogical contexts for Melville’s novella. Beginning with reviews and other materials connected to the tale’s initial publication, the edition will then address several dimensions of the slavery question: the origins and history of the transatlantic slave trade, the domestic debate over slavery, and the transnational history of slave uprisings and rebellions. Additional appendices will present documents on empire and “manifest destiny,” on maritime narratives and travel writing, and on questions of historical memory and commemoration in 19th century America. A final appendix will look toward the future of Benito Cereno by examining two twentieth-century responses to the tale: Robert Lowell’s verse play Benito Cereno and Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem “Captain Amasa Delano’s Dilemma.” This final section will prompt readers to consider the ways in which this tale, and its concern with historical memory, has itself been remembered at other moments of crisis in American history. The text itself poses few editorial difficulties; I anticipate using the 1856 Piazza Tales edition of the text, with variations from the original Putnam’s edition noted in an appendix. Explanatory notes would be devoted to identifying allusions and historical references, and to clarifying and/or highlighting certain details (for instance, noting that the name of the Spanish ship in the story, the San Domingo, was changed by Melville from the Tryal, the name of the ship in Delano’s narrative, in order to highlight the memory of the Haitian revolution.) Melville’s novella is around 34000 words (usually 75 or so pages), while the chapter from Delano’s narrative is roughly 14000 words or 30 pages. Since I 4 anticipate including a number of primary documents to supplement Melville’s brief but rich narrative, I estimate that the total length of the work will be 200 pages or so. I will, of course, adjust the length of the introduction and appendices according to editorial guidance from the Press. I plan to include some non-textual material in the appendices: specifically, visual images documenting the slave trade, the struggle against slavery, and styles of commemoration. If this proposal is accepted, I can complete the manuscript by September of 2010. I believe the proposed Broadview edition of Benito Cereno would find a wide audience of scholars, teachers and students. The polysemous nature of the novella renders it ideal for a wide range of undergraduate and graduate courses, from transnational literature courses to surveys of 19th century US Literature to courses on writing about slavery; from classes on the literature of terror to introductory surveys focusing on narrative technique and other formal issues. I have taught the tale in 19th century American surveys, in a seminar on the American Renaissance, in an American Gothic Literature class and in a course on captivity narratives. The tale’s broad pedagogical possibilities are a key reason why the proposed Broadview edition would succeed, as the proposed range of appendices for the novella would make the edition ideal for a number of classroom contexts. There are several editions of Benito Cereno in print, but nothing that would serve the same purpose as the proposed Broadview edition. The most recent scholarly edition is Wyn Kelley’s Bedford College edition, but other than a reprint of the relevant chapter from Delano’s narrative, there are no historical materials included. Other editions are the Dover Thrift edition of Bartleby and Benito Cereno; a Penguin Classics edition of Billy Budd and Other Stories, a Norton Critical Edition of Melville’s short novels, and numerous editions of The 5 Piazza Tales. While the Norton Critical Edition, edited by Dan McCall, contains a “Contexts” section with a few contemporary sources for each novel, the focus of the edition is on present-day criticism, and space limitations mean that there is no historical material directly connected to Benito Cereno other than Delano’s chapter and a short passage from Melville’s novel Typee concerning cannibals. The proposed edition would correct this deficit, offering students and teachers the ability to examine the relationships between Melville’s masterpiece and a number of contemporary historical issues, while also highlighting the literary legacy of the tale. Overview Introduction: The introduction will provide a biographical introduction to Herman Melville, a review of Melville’s oeuvre, and an assessment of the vicissitudes of his reputation as a writer. Furthermore, the introduction will offer a broad overview of the history of critical responses to Benito Cereno, highlighting several key frameworks in which the tale might be considered. This section will be supplemented by an extensive critical biography. Appendices: I will devote the appendices to the following subjects: A. Background on the Tale Here I will include the introduction to the first edition of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, in which Benito Cereno was first serialized, in order to suggest the type of readership the tale would initially have been expected to garner. I will also include two reviews of The Piazza 6 Tales, Melville’s 1856 collection, in which Benito Cereno was reprinted; the selected reviews single out Benito Cereno for special mention. B. Slave Rebellions and Uprisings This section will contain documents connected to the history of slave uprisings and rebellions. The section begins with an excerpt from a biography of Toussaint L’Overture. since the Haitian revolution is an obviously important intertext for Benito Cereno. Justice Joseph Story’s 1841 decision concerning the 1839 Amistad case, in which the slaves aboard a Spanish slave ship revolted; this case, as Carolyn Karcher has shown, also serves as a key intertext for Benito Cereno, will also be included. Lydia Maria Child’s editorial “The Slave Murders,” responding to a reported case of slaves killing their masters, insists that the slave’s perspective must be, and rarely is, considered in such cases. An excerpt from Frederick Douglass’s novella The Heroic Slave will close this section. This novella, based upon the 1841 rebellion aboard the Creole, makes an interesting point of comparison to Benito Cereno. C. The Debate over Slavery This section will contain a number of documents pertaining to the transatlantic history of slavery and to the debate over slavery in Melville’s day. The first document, an excerpt from the fifth chapter of George Bancroft’s History of the United States, discusses the role of Spain in the founding of the transatlantic slave trade. An excerpt from chapter nine of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicts the sentimental didactic writing style, which, as Peter Coviello and other critics have argued, Melville deliberately opposed in Benito Cereno. The chapter from David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the 7 World both outlines the degradation of slavery and critiques the racial “science” which undergirds the pro-slavery arguments in the next two selections, a passage from William Harper’s Memoir on Slavery and Josiah Nott’s essay. The article from Putnam’s, which appeared in the same issue as the first installment of Benito Cereno, satirizes white stereotypes of African Americans. Finally, the image from Harpers’ Weekly, depicting freed slaves crowded aboard the deck of the illegal slave-trading ship that brought them from Africa and sought to sell them in Cuba, speaks poignantly to the conditions aboard slave ships. D. Empire and “Manifest Destiny” This section links Benito Cereno to the question of empire, both the “Old World” empire brought into the story by Spain and the nascent American one. The excerpt from Stirling’s biography of Charles V resonates with the ghostliness and pallor of Benito Cereno, and its metaphoric depiction of a crumbling Spanish empire. Lyman Beecher’s A Plea for the West defends westward expansion by insisting that Protestant America must counter the forces of Catholicism; Benito Cereno reflects ironically on this type of argument, as neither the Catholic Spaniards nor the Protestant American sailors can lay claim to the moral high ground in the tale. The Putnam’s article “Cuba” defends annexation as a new and peaceful form of empire-building which will eventually lead to global unity. The Ostend Manifesto also defends American annexation of Cuba, in part on the grounds (excerpted for this volume) that Spanish mismanagement of the island will produce a dangerous slave rebellion similar to the one in Haiti. The excerpt from Matthew Maury’s oceanographic study of the Amazon is noteworthy for its suggestion that slavery, blocked from further Westward expansion by the 1850 Compromise, might instead be extended southward, into 8 Latin America, a position popular with many Southerners and expansionists during the 1850s. E. Maritime Narratives and Travel Writing This section contains sailor narratives and other examples of travel writing specifically or thematically linked to Benito Cereno. The chapter from Amasa Delano’s sea narrative, upon which Melville based the novella, will be included here. Leggett’s story is a prime example of “sea Gothic,” a genre to which Benito Cereno might also be said to belong. The ethnographic reflections of Mungo Park and John Ledyard are both directly referenced in different versions of the novella; in the Putnam’s version, Melville refers to the writing of Mungo Park, but the reference is changed to John Ledyard in the Piazza Tales collection, presumably owing to the realization that Park was quoting Ledyard on the question of African women. Finally, the excerpt from Thomas Bowditch’s book depicts the customs of the Ashantee, also referenced in Melville’s tale. F. Commemoration and Historical Memory This section, an important new contribution to the historical contextualization of Benito Cereno, will take up contemporary reflections on the role of history in shaping national consciousness and on the omissions of such histories. The Puritan headstone, with its skeletal imagery, has been linked by Geoffrey Sanborn and other scholars to Benito Cereno’s melancholy perspective on history, and resonates suggestively alongside the use of Don Aranda’s skeleton for the San Domingo’s figurehead within the tale. Daniel Webster’s dedication of the Bunker Hill monument (which was also invoked in the dedication to Melville’s novella Israel Potter, serialized in Putnam’s a few months before 9 Benito Cereno) insists on the patriotic necessity of historical consciousness, while Frederick Douglass’s “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” powerfully demonstrates the erasures perpetuated by that consciousness. Finally, an anonymous fictional pamphlet from Melville’s novel Mardi also takes up the question of the importance of historical memory; the pamphlet’s insistence on the need to attend to the past implicitly, as Allan Moore Emery has shown, rebukes the Young American movement for its exceptionalist failure to take history into account. G. Literary Responses to Benito Cereno This section extends the discussion of historical memory into the 20th century by incorporating two literary works based upon Benito Cereno. Robert Lowell’s verse play, written and produced during the civil rights movement, draws upon but crucially alters some aspects of Benito Cereno, while Yusef Komunyakaa’s poem also seeks to re-imagine the story from the perspective of Delano and the vantage point of the mid-1990s. 10 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Herman Melville: A Brief Chronology A Note on the Text Benito Cereno A. Background on the Tale 1. “Introductory,” Putnam's Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science and Art (January 1853) 2. Selected Reviews of The Piazza Tales: from The Criterion (31 May 1856) from The Knickerbocker, XLVIII (September 1856) B. Slave Rebellions and Uprisings 1. J.R. Beard, from Toussaint L’Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography (1863). 2. Joseph Story, United States v. Libellants and Claimants of the Schooner Amistad, 1841. 2. Lydia Maria Child, “The Slave Murders,” National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 23, 1841. 3. Frederick Douglass, from The Heroic Slave (1852) C. The Debate over Slavery 1. George Bancroft, from History of the Colonization of the United States (1834) 2. Harriet Beecher Stowe, from Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly (1852) 3. David Walker, “Our Wretchedness in Consequence of Slavery” (from David Walker’s Appeal, 1830) 4. William Harper, from Memoir on Slavery (1838) 5. Josiah Clark Nott, from An Essay on the Natural History of Mankind, Viewed in Connection with Negro Slavery (1851) 6. Anonymous. Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, “About Niggers” (October 1855) 7. Image: “Liberated Africans on Deck of Bark ‘Wildfire,’” Harper's Weekly, June 2, 1860. 11 D. Empire and “Manifest Destiny” 1. William Stirling, from The Cloister Life of the Emperor Charles V (1852) 2. Lyman Beecher, from A Plea for the West (1835) 3. “Cuba,” Putnam’s Monthly Magazine (January 1853) 4. James Buchanan et. al., Ostend Manifesto (1854) 5. Matthew F. Maury, from The Amazon, and the Atlantic Slopes of South America (1853) E. Maritime Narratives and Travel Writing 1. Amasa Delano, Narrative of Voyages and Travels, in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, chapter 18. 2. William Leggett, “The Encounter—A Scene at Sea” (1834) 3. Mungo Park, from “Travel in the Interior Districts of Africa” (1816) 4. John Ledyard, from Memoirs of the Life and Travels of John Ledyard (1828) 5. Thomas Bowdich, from Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee: with A Description of that Kingdom (1819) F. Commemoration and Historical Memory 1) Puritan headstone, illustration 2) Daniel Webster, “Bunker Hill Oration” (1825) 3) Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” (1852) 4) Herman Melville, from Mardi (1849) G. Literary Responses to Benito Cereno 1. Robert Lowell, Benito Cereno (1964) 2. Yusef Komunyakaa, “Captain Amasa Delano’s Dilemma” (1996) Select Bibliography