10 - Ancient America Foundation

advertisement

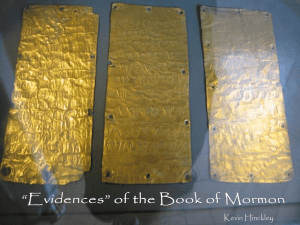

10.4.1 Question: Are the parallels in Popol Vuh to the "tree of life" and the "forbidden tree" that could have originated from the Book of Mormon? 10.4.2 ANSWER: The Book of Mormon teaches the doctrine of the fall from the Genesis tree of life and the forbidden tree (2 Nephi 2:15-20; 42: 2, 7). There are subtle references to the same doctrine taught in story form in the Popol Vuh, Part 11, Chapter 3, that includes both tree symbols. Experts on the Popol Vuh are generally agreed, after much study, that the Popol Vuh is a genuine pre-Columbian sacred book of the Quiche Maya that was not composed around Biblical passages by the Indians, as some have supposed, to gain influence with the Spaniards. We can consider the Book of Mormon book of Nephi as the potential original resource record, because the Quiche chronicler knew there was an ancient book "no longer to be seen" from which his compilation of the Popol Vuh had originated (Recinos 1950:1617). First, an ancient related source contemporary with the Book of Mormon has been observed on Izapa Stela 2, dating to about 200 B.C. In my Izapa Sculpture work (Norman 1976: 94) I compare the Calabash (gourd) tree on Stela 2 with the Popol Vuh underworld "tree of life." I believe there is a direct connection between these two sources. Two figures that appear to be offspring (fruit) of the Stela 2 tree compare to the hero twins, the first ancestors of the Quiche, who were sired when their mother, Xquic, partook of the forbidden gourd tree. They compare to Eve's first two sons born after she partook of the forbidden tree. Other elements of this tree, which others have compared to the Book of Mormon tree of life that imparted eternal life, are the beauty of the tree with its sweet white fruit, and renewed life through the maiden partaking of its fruit. Careful examination of the details reveals that this gourd tree is closer to the "forbidden tree of knowledge of good and evil," and another tree represents the tree of life. The maiden does not seem to have had knowledge that life would come from the tree (through her offspring) until after the fact. The fruit of the gourd tree is not described in the Popol Vuh text as being either beautiful or white. The maiden says, "Is it not wonderful to see how it is covered with fruit" which "must be very good?" Her wonderment was that the previously barren tree had become fruitful, not that it was beautiful. An assumption of beauty equating with white fruit can be made from the skull bone of Hun-Hunahpu placed in its branches being naturally white and the fruit matching the skull. In reality, the gourd is green, and only after losing its husk does the dried gourd pod take a beige color that resembles the skull. The skull of Hun Hunahpu hidden in the tree lamented that it had no flesh, because "the flesh is all which gives . . . a handsome appearance," and after death, "men are frightened by their bones." So any whiteness in this context implies a bone fear of death, not beauty, joy, and life. Tedlock's Popol Vuh translation (page 114, footnote on page 274) observes that the reference to desirable, delicious fruit has to be metaphorical because the gourd is not edible, but the mystery is unsolved. Does it survive from an original tree of life or forbidden fruit account in the Book of Mormon? An implied Book of Mormon tree of life correspondence is really nearer to Eve's encounter with the Genesis "tree of knowledge of good and evil" than to the tree of life. Adam and Eve were forbidden to partake of the fruit in consequence of death, and when Eve partook, they were cast out to the earth where they became mortal, had children, and became subject to death. They also had two sons, Cain and Abel, who became locked in a life-death struggle that introduced the ultimate evil of murder as part of the fall that had to be overcome by the redemption of Christ. This compares to the ancestral twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque of the Popol Vuh, who were locked in a life-death struggle with their two elder brothers. Because of their abusiveness, the two elder brothers were changed through sorcery into animals that resembled monkeys and went off and lived in the forest (Part II, Chapter 5). This compares to the elder brothers Laman and Lemuel who became cursed because of their rebellion and began living primitive lives in the forest (2 Nephi 5:21, 24). In this, we appear to have a Genesis account mixed with the original ancestors from Lehi's first four sons in the Book of Mormon. The inhabitants of Xibalba were forbid en to approach the gourd tree, and the maiden in anticipation of partaking of its fruit said: "Must I die, shall I be lost, if I pick one of this fruit?" It was enticing, but a fear of death lingered from the skull that hung in this forbidden tree. I prefer this translation from Recinos rather than Tedlock's translation, who felt this passage makes more sense if it refers to the fruit dying and being wasted rather than the maiden. The real tree of life in the Popol Vuh myth was not the Calabash but another tree. Upon her partaking of the Calabash, a judgment of death by sacrifice was pronounced upon the maiden, but she escaped death through the mediation of a "tree of light" that glowed when it provided red sap as a substitute for her blood and heart for a sacrifice in her behalf so that she could be exiled to the earth and live. The tree is identified as the Chuh Cakche, a large tree the Mexicans called ezauahuitl, "tree of blood," also identified in Chiapas, and in Guatemala where it is called Pilix and Cancante that is also distinguished for its white leaves and stems. Is not this white "tree of light" a direct reflection from the Book of Mormon tree of life? An important point of correspondence, according to Mormon theology, is the condition that the human race would not have been propagated without Adam and Eve being exiled to the earth after partaking of the forbidden tree's fruit. Also, consequence of death that came with mortality was overcome through the atoning blood sacrifice of Christ as mediator in their behalf. And we learn from the Book of Mormon that the tree of life that ensured eternal life was the symbolic embodiment of Christ as the Redeemer through his atoning sacrifice (I Nephi 11). -V. Garth Norman References Norman, V. Garth. 1976. Izapa Sculpture; Part 2 Text. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, No. 30. Provo. Recinos, Adrian. 1950. Popol Vuh, the Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiche Maya. English version by D. Goetz and S. G. Morley from Spanish translation by Adrian Recinos. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman. Tedlock, Dennis. 1985. Popol Vuh; A Definitive Edition of the Maya Book of the Dawn of Life, and the Glories of God and Kings. Simon and Schuster, New York.