earthquake article

advertisement

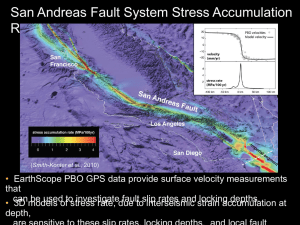

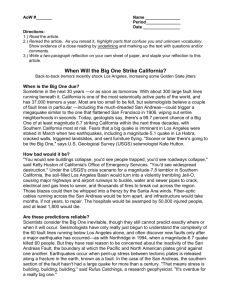

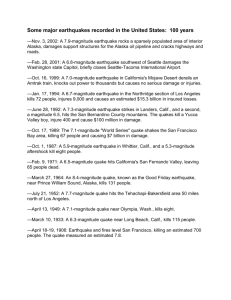

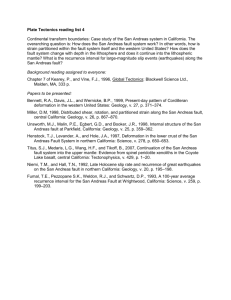

THE ORIGINS OF KILLER QUAKES A FEVERISH SEARCH FOR DANGER SIGNS Adherents of the theory of plate tectonics, which revolutionized earth science during the 1960s, say that the world's surface is a mosaic of rigid plates floating slowly around a semimolten interior. Some plates are giant slabs of ocean floor, others are a combination of continent and ocean floor. The constantly moving plates sometimes glide past each other with relative ease. But they occasionally grind together like ice floes, sometimes sticking together, with pressure building up, then breaking free with explosive force, causing an earthquake. The San Andreas Fault, where the Pacific Ocean plate rubs against the North American plate, is particularly susceptible to this phenomenon. Scientists say that the way the plates in that region sometimes grind against each other is responsible for the earthquakes that regularly erupt in California. The main fault line, which stretches 800 miles almost along the entire length of California and reaches within one mile of San Francisco and 30 miles of Los Angeles, is the best understood of all fractures in the earth's crust. The San Andreas Fault moves at a rate of 1.4 inches each year, occasionally producing substantial quakes. But that is where certainty stops. California actually has a spider's web of smaller cracks-not all of them visible branching off from the San Andreas Fault, all with different rates of movement. And two years ago, seismologists discovered a major hidden group of subterranean faults in the Los Angeles basin that constitute a whole new class of earthquake hazards. They have added a host of imponderables to the inexact science of earthquake prediction. Foreshocks: Dieter Weichert, acting director of the Pacific Geoscience Centre near Victoria, said that the number of major earthquakes that scientists have been able to predict accurately is "negligible." There are various signs that could signal a quake, he added, but none of them is definite. One sign is a series of smaller foreshocks in an area where that kind of activity is unusual. Foreshocks alerted scientists to the China quake of 1975, but those warning signals are easily overlooked in California, which experiences thousands of tremors every year. As for last week's earthquake, seismologists said that there were one or two shocks that in hindsight could have been interpreted as foreshocks, but they were not particularly unusual for the area and did not appear to be cause for alarm. Severity: Weichert added that when the ground begins to rise-usually by a few inches-in the vicinity of a fault, it can be a sign that a quake is imminent. But that phenomenon, too, offers no certainty that an earthquake will occur, nor of the likely severity of an upheaval. As a result, most scientists rely on the seismic gap theory, which was developed at New York City's Columbia University during the 1970s. According to that theory, the likeliest place for an earthquake to occur is the spot along a fault that has been quietest for the longest time, building up the most tension. Using that reasoning, the U.S. Geological Survey predicted in 1988 that there was a 60per-cent chance that another so-called great quake-which would dwarf last week's upheaval-would strike southern California within 30 years. Clarence Allen, a seismologist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said that the highest probability of such a quake appears to be in the Coachella Valley, south of Palm Springs, Calif. That segment of the San Andreas Fault has been dormant for at least 196 years, far longer than most others. Rupture: A "great quake" measures more than 8 on the open-ended Richter scale (a system devised in 1935 by American seismologist Charles Richter), with each succeeding number representing a tenfold increase in the strength of the tremor. California has had only two quakes of that magnitude in recent history: one in 1857 that produced a 180-mile-long rupture in the Mojave Desert, east of Los Angeles, and the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, which scientists estimate would have measured 8.3 on the Richter scale and which killed 700 people, many of them from a disastrous fire that followed the quake.