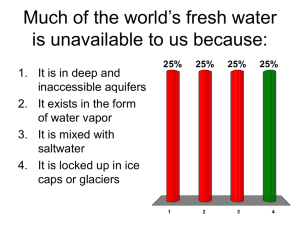

5 Potentials and Problems of Water Resources Management and

advertisement