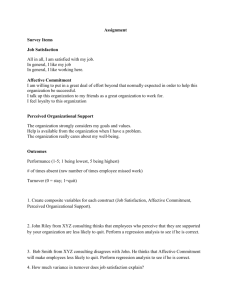

Running head: AFFECTIVE CLIMATE AND TEAM PERFORMANCE

advertisement