Chapter outline

advertisement

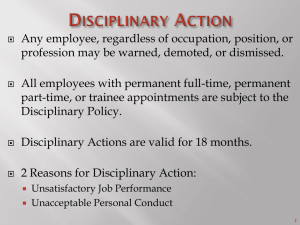

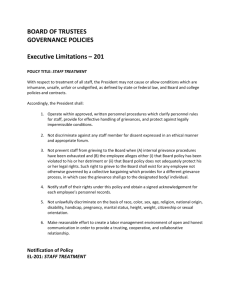

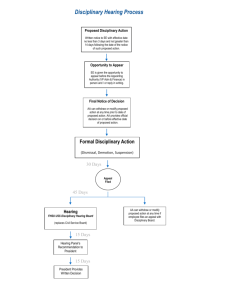

HRM At Work: Student Notes Chapter 11: Fairness at Work – Procedures and Policies Chapter overview This chapter discusses the use of employee relations procedures and how they can be used as a way both to resolve difference and to engender commitment. The chapter opens with the definition of policies and procedures and a brief discussion of how their use relates to the broader employee relations context. After working through this chapter, you should be able to understand the various functions in which procedures and policies can be used, to devise formal procedures, and to offer advice on the handling of discipline/grievances. You should also be able to show how procedures can enhance commitment and provide HR practitioners with a means of offering support to line management. Chapter objectives After studying this chapter, you should be able to: devise procedures that help to achieve fairness and consistency at work advise line managers on how to handle disciplinary and grievance cases work in partnership with other managers during the collective bargaining process And you should understand and be able to explain: the value of procedures in helping to create a positive psychological contract the principal components of, and differences between, disciplinary and grievance procedures the way in which HR specialists may provide support for line managers in operating procedures. Chapter outline The nature and extent of procedures The chapter begins with a discussion of the extent to which procedures are used, and the nature of these procedures, using available data to describe the current context, as well as referring to theory to help you understand the nature of procedural practices. This involves discussing areas in which procedures may be used: recognition, disputes, grievances, discipline, redundancy and equal opportunities The case for procedures We then outline the case for procedures in employee relations, the reasons for including procedures being listed and discussed: they can help to clarify the employment relationship they can provide a mechanism for resolution or act as a safety valve they can ensure consistency they can lead to more systematic record-keeping, thereby improving information systems they may be important in the event of defending a case before an employment tribunal and the process of developing procedures alongside the potential for joint ownership can enhance the employment relationship. Procedural adequacy can be assessed using Marsh and McCarthy’s twin criteria – acceptability and appropriateness. Both of these are in large part a function of the context. Disciplinary procedures The discussion of disciplinary procedures centres on the Industrial Relations Act 1971 and outlines some potentially fair reasons for dismissal: lacking capability, misconduct or redundancy. Automatically unfair reasons for dismissal are listed: pregnancy, trade union involvement, whistle-blowing, asserting a statutory right, raising health and safety issues, or working in contravention of the Working Time Regulations 1998. The key elements of disciplinary procedures (as per the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service [ACAS] code of practice) are listed, including that procedures should: be specific allow for speedy resolution indicate potential disciplinary actions stipulate levels of authority/management allow for those being disciplined to state their case and allow trade union representation. Grievance procedures There follows discussion of grievance procedures and an outline of six pieces of advice – these procedures should: be simple where possible, be quick and informal include elements of representation be communicated to employees and managers be explained to line managers in training sessions and be implemented with consistency. Line managers and the use of procedures, and the contribution of HR specialists to the bargaining process We then move on to a more broad-ranging discussion of the role of procedures in line management, and the section on the contribution of HR specialists to the bargaining process (analysis, identification of tradable items, aims and strategy, presenting proposals, confirmation of common ground, adjournment and factors to consider in concluding). Conclusions By the end of this chapter you will have reviewed a number of the procedures that provide a framework for employee relations. In the current climate – where concepts of flexibility, empowerment and de-layering reign supreme – procedures are seen by some commentators as an anachronism, However, you should remember why procedures were introduced in the first place, and the purposes they serve. Procedures are an essential element of good employment relations and HR practice because they provide a clear framework within which issues can be resolved. Feedback on mini-questions Write down three procedures operating at your workplace and explain their purpose. How successful are they in meeting their purpose? If you are currently working, it should be relatively straightforward to identify three procedures. These might serve various functions. For example, a well-written procedure can make it easier for those who do not understand how to operate a machine or carry out a complex process to do a job without having to ask for help. Similarly, for health and safety reasons it may be necessary with some equipment to specify the ways in which machinery should and should not be operated. More in line with the terms of this chapter, many organisations will have procedures relating to any or all of the following: recruitment policy/practice, the means of assessing and deciding promotions, discipline, grievances, training and development provision, and appraisal or reward processes. If you do not have this level of practical experience, you will be able to track down examples of discipline and grievance procedures – as well as other instances – from published case study research. Where it is not possible to get sufficient detail to explore the effectiveness of these procedures, you will still benefit from assessing and analysing the language used in such documents speculatively to assess the extent to which they are likely to be effective. How well does informality work in resolving workplace problems? Has such an approach been attempted in your organisation or in one with which you are familiar? If so, why was it successul or unsuccessful in the circumstances? Formal disciplinary and dismissal procedures had by the turn of the millennium become almost universal in all but the smallest workplaces. Since then, even small non-union firms have witnessed an increase in formal procedures prompted by changes in legislation and the growth of individual employment rights (Kersley et al, 2006, p.234). The Industrial Relations Act 1971 first introduced the notion of unfair dismissal. Thereafter, there has been considerable formalisation, largely due to the growth in the numbers of cases taken to employment tribunals. Frequent references are now made to the benefits such procedures bring for managers (such as clarifying authority, indicating processes to be followed) and greater managerial acceptance. Small firms are less likely to have formal policies in place, probably because owners rarely possess the specialist knowledge to construct such policies or the inclination/resources to employ professionals for this task. The owner is likely to work in close proximity to employees as well as managing the employment relationship. This creates an environment of ‘teamwork’ (Goss, 1991), but the team analogy is vulnerable when ownership authority must be reinforced. Evidence indicates that rather than risk disrupting the ‘team’ environment, small firm owners resist using formal policy or practice, preferring a negotiated solution to employment-related issues, which avoids overt conflict What should be the division of responsibility between line managers and HR specialists in relation to disciplinary practice and procedures? What factors should influence this, and why? The paragraphs before and after this question offer a good start as to the role of the HR function in theory. HR people are ‘the guardians or custodians of procedures’ – they may have designed the procedures and often have an influence over their implementation, even where they are not always visibly involved. It is very important that HR managers understand the realities of trying to implement these procedures at ground level – in other words, to show awareness of the organisational context, customs and culture, as well as the national/legal contexts. Otherwise, they may seem out of touch and therefore removed from decisionmaking. If you have relevant experience, you will be well placed to assess whether the HR function in your organisation is typically a provider of information as opposed to a partner or specialist adviser involved and consulted on a more regular basis. You should try to link this back to the early discussion of the various roles that HR can adopt (perhaps clerk of the works versus architect). It is likely that even in the best-run organisation there will be scope for improvement in the design and implementation of procedures. Perhaps you could revisit one of these areas to examine how such procedures are generally perceived (perhaps as red tape or a bureaucratic constraint) with a view to reinterpreting them as potentially beneficial (perhaps in communicating procedural justice or safeguarding organisations in a ‘compensation culture’). Think of an attempt at disciplinary action by an employer that went wrong and explain why it occurred. What could have been done to stop it from going wrong? The previous section outlines some of the key features of disciplinary procedures in line with the ACAS code of practice. Each of these is potentially relevant to your understanding of this question. The code of practice states that disciplinary procedures should: be in writing; be specific in terms of who they apply to; allow for swift resolution; indicate the range of potential disciplinary actions; stipulate levels of management and authority – so that immediate line managers do not have the power to dismiss employees without consulting and referring the matter to senior management; allow for people to be advised of complaints against them, and to be given an opportunity to state that case prior to judgement; allow people to be accompanied by a fellow employee or trade union representative; ensure that employees are not dismissed for a first breach of discipline; ensure that no action is taken prior to careful investigation; ensure that employees are provided with an explanation for any action taken; and provide the right of appeal. In summing up the character of these recommendations, one could say that they are informed by the principles of natural justice. In other words, the fairest procedures are transparent and explicit; they allow for both sides to put their case; they allow for appeal. Attempts to discipline can be subverted in the same way that management prerogative can be subverted. A form of disciplinary action might take the form of telling an employee not to do something (eg send personal email, receive personal phone calls). Often in instances like this, particularly where the employee cannot see any reason for such an order, the action can be subverted (talking to friends/relatives as though to a customer) and its incidence could even increase. Go to the library and find a recent copy of one of the specialist employment law publications – such as the Industrial Relations Law Report or IRS Employment Review. Choose a recent case, examine the details, and write a short report outlining any lessons to be learned from the case. Try to find a high-profile (high-cost) case for which the organisation has a large degree of potential ‘exposure’ (eg an absence of policies or relevant procedures) – this will be of interest to your managers. The implication of this as an end goal is that you should spend some considerable time researching cases, rather than seize upon the first one that catches your eye. The results of your research could form the basis for a group discussion. This exercise can serve to demonstrate that HRM practitioners may be able to expand their sphere of influence. Get a copy of two organisations’ grievance procedures, and compare them. What are the major differences between them? Why are there such differences? How might the procedures be improved? If you do not work for an organisation with a grievance procedure, try to obtain grievance procedures from two different types of organisation. In a highly bureaucratised public-sector organisation (eg a branch of the civil service), it is likely that the grievance procedure will be very different from that in a private-sector company. You will learn from comparing these procedures. If you are currently working for an organisation with a grievance procedure, choose between a) comparing your own organisation’s procedure with that of a company in a related line of work or sector, and b) comparing your own procedure with that of a company in a very different line of work or sector. The advantages of looking at a similar company are that there may be considerable commonality and overlap in the use of language, frames of reference and industry-specific issues (the issue of intellectual property, for example). The benefits of looking at a very different context are that it can encourage a more strategic reappraisal of the existing procedure, perhaps informing the trade-off between transparency, consistency and detail on the one hand, and a more holistic vision of the relationship between employee and employer, promoting thinking ‘beyond contract’, on the other.

![Labor Management Relations [Opens in New Window]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006750373_1-d299a6861c58d67d0e98709a44e4f857-300x300.png)