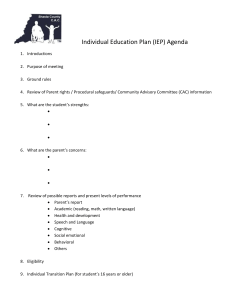

Northbridge Public Schools BSEA #02-3722

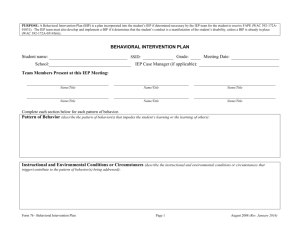

advertisement