Voluntary code of practice - Disability Services Commission

advertisement

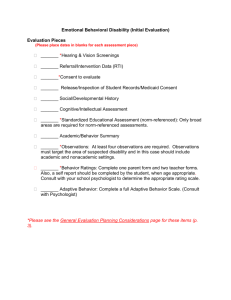

Voluntary Code of Practice for the Elimination of Restrictive Practices Disability Services Commission August 2012 Contents Overview ...................................................................................................................... 1 Part One — Overview of the purpose and context of the code of practice ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Context .............................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Key terms and definitions ................................................................................ 2 Part Two — Development of operational policy and guidelines to assist with service implementation.................................................................... 2 2.1 Considerations to achieve systemic change in service delivery.................. 2 2.2 Service Guidelines ............................................................................................ 3 2.3 Code of practice review .................................................................................... 7 Appendices 1 International, National and State Obligations................................................. 9 2 Definitions and Key Terms ............................................................................. 11 To support disability sector-wide engagement in the elimination of restrictive practices Overview This code of practice provides the basis for the disability sector to develop operational policy and guidelines for eliminating the use of restrictive practices. It applies to all services provided and funded by the Disability Services Commission for children and adults with disability. The code of practice has been developed by a coalition of partners from across the disability sector. Disability sector organisations are strongly encouraged to adopt the practice guidelines contained within the voluntary code which is consistent with Standard 9 of the Disability Service Standards. Support and training for implementation of the code of practice is available through the work of the Positive Behaviour Framework Guiding Committee. This code of practice is divided into two parts: Part One which provides an overview of the purpose and context for the code of practice. Part Two which is to inform the development of operational policy and guidelines to assist with service implementation. Part One — Overview of the purpose and context of the code of practice 1.1 Purpose The purpose of this code of practice is to: 1.2 Contribute to the elimination in the use of restrictive practices for people with disability who sometimes exhibit challenging behaviours ensure safeguards are in place in exceptional circumstances where it is necessary to use restrictive practices to protect the welfare of individuals and the safety of third parties. Context The Commission’s 2009 Positive Behaviour Framework has promoted a coordinated statewide approach to Positive Behaviour Support and has been guided by the Towards Responsive Services for All report in the implementation of this strategy. The essential elements of Positive Behaviour Support are highlighted in a paper developed after 1 sector-wide consultation (the Effective Service Design report) which highlights those elements of service design and delivery that if applied, would lead to a significant reduction or elimination in the need for use of restrictive practices. This code of practice on eliminating restrictive practices is the next stage of implementing the Positive Behaviour Framework and has been jointly developed by representatives from a broad range of disability sector organisations, people with disability, families, carers, advocacy organisations, other government agencies including the Office of the Public Advocate and State Solicitor’s Office, and the Commission. International, national and state obligations in relation to the human rights of people with disability underpin the development of this code of practice (refer to Appendix 1). 1.3 Key terms and definitions Key terms associated with the identification, reduction and elimination of restrictive practices are defined in Appendix 2. For terms which have been bolded in this document please refer to Appendix 2. Part Two — Development of operational policy and guidelines to assist with service implementation 2.1 Considerations to achieve systemic change in service delivery The implementation of this code of practice will require systemic change over time in the Western Australian disability services sector. Considerations for the disability sector to achieve this include: significant changes in current service design and practices significant cultural change increased interdisciplinary liaison and collaboration between services new approaches to staff training. The well-being and safety of people with disability, their families and the staff who provide services will be a primary consideration during the transition from old to new practices as required by this code of practice. Operational implementation of the policy will be the responsibility of each service provider and will take into account the types of service provided and the assessed needs and abilities of each person for whom the services are provided. Service providers should only withdraw existing restrictive practices when they are satisfied that: safe and more respectful alternatives have been developed staff have had the appropriate training 2 staff have demonstrated the skills required to support the person under the new arrangements Where a Guardian with the relevant authority has been appointed, he/she has consented to the withdrawal of the practice. 2.2 Service Guidelines The following service guidelines are to be considered when delivering services to people who sometimes exhibit challenging behaviours. These guidelines are driven by the assumption that people with disability are in the best position to make decisions and choices for themselves and have the capacity to communicate these. Where people display complex behaviours and before any consideration is given to the potential use of a restrictive practice, this assumption must be confirmed. 2.2.1 Effective Service Design Service providers will have policies, procedures and tools in place to safeguard the rights of people with disability and monitor the use and elimination of restrictive practices. Effective service design starts with approaches that are person-centred and proactive and that have enhancing the quality of life for the person as their focus. Service providers will adopt best practices that support and maximise the person’s decision making, choice and self direction. The service provider is responsible for ensuring that the person is giving informed consent in relation to all matters that effect them and understands the nature and consequences of their consent. This includes understanding the impact on them of any prescribed restrictive practice that might result from their consent. 2.2.2 Services providers will recognise that people with disability have the same rights as all people to equality before the law and to equal protection under the law, without discrimination. 2.2.3 The primary focus of services is to uphold human rights and the well-being, inclusion, safety and the quality of life of people with disability. 2.2.4 Service providers will recognise that people with disability and their families and carers are the natural authorities for their own lives and are in the best place to communicate their choices and decisions. 2.2.5 Service providers will implement processes that recognise the person’s authority in decision making, choice and control will guide the design and provision of services. 3 2.2.6 Services providers will recognise that the use of restrictive practices may reflect a failure in the service system to understand the nature and function of the individual’s behaviour. 2.2.7 Service providers will recognise that the use of restrictive practices is not an effective long term strategy to manage risks and behaviours and can result in long term physical and psychological harm. 2.2.8 Service providers will actively facilitate the person’s engagement with family, carers, other friends and advocates who know them well, are concerned for their best interests and can support them in decision making, unless there is clear evidence that the person does not consider this to be in their best interest. 2.2.9 Service providers will recognise that substantive equality is integral to the service provision. Cultural relevance and appropriateness of services, in a person-centred context, is an important consideration but does not over-ride the requirement for the human rights of the person with disability to be the paramount consideration. 2.2.10 Use of Restrictive Practices Restrictive practices may only be implemented: - with a prior review at a senior level in the organisation that confirms the evidence that all less restrictive alternatives have been carefully evaluated and cannot be applied - as a last resort, when the person presents a risk to themselves and/or others - for the least time possible - with the informed consent of the person involved - after there has been an assessment of the impact of the practice on the rights and well-being of others who share the person’s environment - under the supervision of a designated, experienced staff member who is on duty at the time - when contained in a clearly documented behaviour support plan where a Guardian has been appointed with the relevant authority and that s/he has consented. 4 2.2.11 Restrictive practices are not acceptable and cannot be approved for organisational or staff convenience, or to overcome a lack of staff, inadequate training, or a lack of staff support and/or supervision 2.2.12 Prescribed restrictive practices must be recorded at each event and reviewed by the service provider at least every 12 months. 2.2.13 From time-to-time emergencies might occur in which an immediate and otherwise unacceptable response might be required. Restrictive practices for which there has been no prior prescription or consent, including seclusion and physical restraint, may be used in an emergency to save a person's life or to prevent them from experiencing serious physical or psychological harm, or to prevent the person causing serious physical or psychological harm to another person. 2.2.14 When a restrictive practice is used that has not been previously prescribed: the circumstances in which the practice was used must be reviewed by the service provider within seven days, to reduce the risk of a recurrence and must be reported to the Commission as a Serious Incident Report within seven days. 2.2.15 Consent The service provider is responsible for ensuring that everyone involved in supporting the person in these circumstances understands the nature and consequences of the person’s consent. This includes understanding the impact on them of any restrictive practice that might result from that consent. The service provider will use whatever strategies are necessary to facilitate the person’s capacity to communicate their choices and decisions. When: - there is uncertainty about the person’s capacity to provide informed consent - there is an absence of engaged family, carers, other friends and advocates to assist the person to make decisions - there are conflicts around what decisions and actions are in the person’s best interests 5 the service provider will seek the advice and guidance of the Office of the Public Advocate for adults, and the Department for Child Protection for children under 18 years of age, as to the appropriate action to take. 2.2.16 Use of a Therapeutic Device The use of a therapeutic device does not constitute a restrictive practice when it is clinically prescribed for the purpose of: improving the quality of life of a person with disability, by preventing or minimising body shape distortions and the directly related secondary complications that result in pain, discomfort, and poor health and/or assisting a person to participate in a desired task or activity by minimising factors which impede them, and enabling their engagement in an activity which would not otherwise be possible and/or providing treatment1 for a person by preventing that person from injuring themselves in cases where, if there were no restriction of the person, a significantly adverse health outcome would occur. A device may be used for these purposes if its use: is clinically prescribed by an appropriately qualified health professional such as a registered medical practitioner, occupational therapist, a physiotherapist, a speech pathologist, a dentist, a podiatrist or an orthotist2 is formally and regularly reviewed has the informed consent of the person or their representative 3 (in cases where the person cannot give informed consent, service providers such as allied health professionals have no authority under the Guardianship and Administration Act 1990 to make a treatment decision, whether this is to consent or withhold consent for treatment). In the Guardianship and Administration Act 1990, the term “treatment” refers to any medical, surgical or dental treatment or other health care, including life sustaining measures and palliative care. 2 The definition of a “health professional” is a person registered under the “Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Western Australia)” as set out in the Civil Liability Act 2002, Section 5PA. For list, see Appendix 2. 3 See Appendix 2 “Decisions About Treatment”. 1 6 The prescribed device must be the least restrictive alternative to achieve the desired therapeutic result and be based on evidence from current best practice. NB: The use of a device (eg arm splints) for the management of behaviour is however considered to be a restrictive practice. 2.2.17 Use of Medication The appropriate use of psychotropic and other drugs to reduce symptoms and behaviours associated with conditions such as anxiety, depression and other mood disorders or a psychosis, does not constitute a restrictive practice when: the medication is prescribed for a person who has a psychiatric condition diagnosed by a qualified psychiatrist and is reviewed at least annually or the medication is prescribed by a general practitioner who is treating the person as part of a Medicare approved mental health plan and the medication is reviewed at least annually. 2.2.18 Use of Environmental or Psycho-social Restraints Whether or not an environmental restraint or a psycho-social restraint would be considered to be a justifiable4 restrictive intervention for the purposes of this code of practice requires the service provider to make a case-by-case decision which takes into account: the age of the person — some interventions might be restrictive in relation to adults, but reflect broader, accepted community values and practices in relation to the protection of children whether the intent of the restriction is to punish or over-protect, or is to meet a duty of care or an occupational health and safety requirement the balance between the rights of the person and the rights of all others who share the person’s environment. Such practices, when prescribed, must be formally and regularly reviewed. 2.3 Code of practice review In acknowledgement of the importance of the implementation of this code of practice, the Commission will initiate a review no later than December 2013. 4 A justifiable restrictive practice is one that is implemented as per section 2.2.10. 7 For further information contact: Jacki Hollick Manager Statewide Positive Behaviour Strategy Statewide Specialist Services Author: Mike Cubbage Manager Behaviour Support Consultation Team Statewide Specialist Services Date: August 2012 8 Appendix 1 International, National and State Obligations The following have informed the development of the code of practice: Universal Declaration of Human Rights United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, with particular reference to: Article 4 1(b): To take all appropriate measures, including legislation, to modify or abolish existing laws, regulations, customs and practices that constitute discrimination against persons with disabilities. Article 4 1(c) To take into account the protection and promotion of the human rights of persons with disabilities in all policies and programs. Article 4 1(d) To refrain from engaging in any act that is inconsistent with the present Convention and to ensure that public authorities and institutions act in conformity with the present Convention. Article 4 1 (e) To take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination on the basis of disability by any person, organisation or private enterprise. Article 14 Liberty and Security of the person. Article 15 Freedom from torture or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment. Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 Disability Discrimination Act 1992 Disability Services Act 1993 Children and Community Services Act 2004 Guardianship and Administration Act 1990 9 Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA) Carers’ Recognition Act 2004 WA Disability Services Standards specified by the Disability Services Act 1993 Positive Behaviour Framework: Effective Service Design 2010. 10 Appendix 2 Definitions and Key Terms There are various interpretations in the disability service sector of key terms associated with the identification, reduction and elimination of restrictive practices, but the following definitions are adopted for the purpose of this code of practice. The first five terms defined below have been agreed at a national level by the Disability Policy & Research Working Group (DPRWG), a standing committee of the Community and Disability Services Ministers’ Advisory Council (CDSMAC). Restrictive intervention A “restrictive intervention” is any intervention and/or practice that is used to restrict the rights or freedom of movement of a person with disability including: Seclusion “Seclusion” means the sole confinement of a person with disability in a room or physical space at any hour of the day or night where voluntary exit is prevented. Chemical restraint A “chemical restraint” means the use of medication or chemical substance for the primary purpose of controlling a person’s behaviour. It does not include the use of medication prescribed by a medical practitioner for the treatment of, or to enable treatment of, a diagnosed mental illness, a physical illness or physical condition. Mechanical restraint5 A “mechanical restraint” means the use of a device6 to prevent, restrict or subdue a person’s movement or to control a person’s behaviour but does not include the use of devices for therapeutic purposes.7 Physical restraint A “physical restraint” means the use or action of physical force to prevent, restrict or subdue movement of a person’s body, or part of their body, for the primary purpose of controlling a person’s behaviour. Physical restraint does not include physical assistance or support related to duty of care or in activities of daily living. Environmental restraint An “environmental restraint” restricts a person’s free access to all parts of their environment. 5 To be consistent with the international research evidence it is important to differentiate mechanical vs physical restraints. 6 A device may include any mechanical material, appliance or equipment. 7 Therapeutic purposes may include, for example, safe travel such as seat belts during transportation or arm splints as part of occupational therapy. 11 Examples of environmental restraints include, but are not limited to: barriers that prevent access to a kitchen, locked refrigerators, restriction of access to personal items such as a TV in a person’s bedroom locks that are designed and placed so that a person has difficulty in accessing or operating them restrictions to the person’s capacity to engage in social activities through not providing the necessary supports that they require to do so. Psycho-social restraint “Psycho-social restraint” is the use of “power-control” strategies. Examples of psycho-social restraints include but are not limited to: requiring a person to stay in one area of the house until told they can leave directing a person to stay in a unlocked room, corner of an area or stay in a specific space until requested to leave (also known as “exclusionary time-out”) directing a person to remain in a particular physical position, (e.g. laying down) until told to discontinue “over-correction” responses (e.g., requiring a person who has spilled coffee to clean up not only the spilled coffee but the entire kitchen) ignoring withdrawing “privileges” or otherwise punishing, as a consequence of non cooperation. Therapeutic device A “therapeutic device” is primarily used to improve function (motor and bodily) and to prevent or reduce the risk of body shape distortion and their/its subsequent secondary complications. Therapeutic devices employ a variety of methods used for the purpose of restricting the movement of the person due to high or low tone and/or postural deformity and in some instances behavioural movements. They may also be used for short periods of time to allow for wound healing/tissue repair. The use of a therapeutic device aims to minimise the person’s risk of developing physical deformity/injury that leads to the development of pressure on the soft tissues, to the development of pain or a reduction in functional capabilities. Examples of therapeutic devices include, but are not limited to: postural supports such as inserts splints to minimise contractures shoulder, chest, pelvic straps for optimal postural support helmets seatbelt modifications for safe transport night time positioning equipment sensory devices such as weighted blankets or vests. 12 Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) Positive Behaviour Support (PBS) is a multi component intervention model that has evolved from behavioural techniques and applied behaviour analysis. The key identified components of PBS are: assessment-based interventions; reduction of punishment approaches; inclusion of all relevant stakeholders; a long term-focus; prevention through education, skill building, environmental redesign, enhanced opportunities for choice, staff development, resource allocation, provision of incentives, systems change; improved quality of life involving robust and significant person-centred outcomes for the individual, their family and other stakeholders; ecological and social validity and contextual fit. Least Restrictive Alternative The principle of least restrictive alternative recognises the right of a person to live in an environment which is the most supportive and the least restrictive of his/her freedom 8. In the context of the use of a restrictive practice it requires that service providers engage in actions that: a) ensure the safety and well-being of the person and all others who share their environment b) having regard to (a) above, impose the minimum limits on the freedom of the person as is practicable in the circumstances. Informed Consent The notion of “informed consent” requires careful and special consideration, and must always be assessed on a case-by-case basis. Informed consent means a person: is provided with appropriate and adequate information is capable of understanding the nature of the information and the consequences of a decision made in relation to this information can freely decide for him or herself without unfair pressure or influence from others. In obtaining informed consent, the service provider must consider the following: Information might need to be provided in different ways depending on the person’s disability, needs and mental state at the time. What the consent applies to must be very clear. For example, with regard to sharing of information, the person should be informed about what information will be shared, with whom and how. Care should be taken to avoid assumptions that consent provides a blanket approval, or that consent on one occasion or about one event implies consent for future occasions or events. 8 Parliamentary White Paper on Services for People with Intellectual Disability in Queensland (1988) cited in www.cmc.qld.gov.au/.../report-of-an-inquiry-into-allegations-of-officialmisconduct-at-the-basil-stafford-centre-part-3” 13 The person should be informed that they have the right to change/retract their consent. Failure to observe the requirements necessary for informed consent to be obtained can result in the infringement of a person’s rights. Decisions about treatment9 Under the Guardianship and Administration Act 1990, the term “treatment” refers to any medical, surgical or dental treatment or other health care, including lifesustaining measures and palliative care. Under the same act a “treatment decision” is defined as a decision to consent or refuse consent to the commencement or continuation of any treatment for the person. In cases where decisions are required about a course of treatment for an adult who is not capable of making reasoned decisions, the Guardianship and Administration Act 1990 allows for substitute decision makers to be appointed by the State Administrative Tribunal. A person thus appointed to make personal, lifestyle and treatment decisions is known as a guardian. To protect a person’s decision making rights wherever possible, a guardian will be appointed only if it is considered necessary to safeguard the best interests of a person aged 18 years or older, whose decision making capacity is impaired and if other less restrictive options are not available or appropriate. Process for obtaining a treatment decision All decisions regarding children should be made by their legal guardians. In the case of adults, the Guardianship and Administration Act 1990 specifies a procedure to be followed when treating a person aged 18 years or over who is incapable of making a treatment decision due to a decision making disability. The request for consent for treatment must be sought from a hierarchy of decision makers who themselves are adults (18 years or older), have full legal capacity, are reasonably available and are willing to make the decision. Hierarchy of treatment Decision makers is set out under the Guardian and Administration Act 1990, Section 110ZD and Section 110ZJ: Office of the Public Advocate, “Position Statement. Decisions about treatment”, Government of Western Australia, Department of the Attorney General. 9 14 Advance Health Directive (AHD) Decisions must be made in accordance with the AHD unless circumstances have changed or could not have been foreseen by the maker. Where an AHD does not exist or does not cover the treatment decision required, the health professional must obtain a decision for non-urgent treatment from the first person in the hierarchy who is 18 years of age or older, has full legal capacity and is willing and available to make a decision. Enduring Guardian with authority Guardian with authority Spouse or de factor partner Adult son or daughter Parent Sibling Primary unpaid caregiver Other person with close personal relationship If none of the above are reasonably available or willing to make the decision, a guardian may need to be appointed. In situations where the decision making process is unclear it is best to seek the advice of the Office of the Public Advocate (contact details provided at the end of this document). Health Professional Civil Liability Act 2002, Section 5PA 5PA. Term used: health professional “health professional” means— (a) a person registered under the Health Practitioner Regulation National Law (Western Australia) in any of the following health professions — (i) chiropractic (ii) dental 15 (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) medical nursing and midwifery optometry osteopathy pharmacy physiotherapy podiatry psychology or (b) any of the following — (i) a medical radiation technologist as defined in the Medical Radiation Technologists Act 2006 section 3 (ii) an occupational therapist as defined in the Occupational Therapists Act 2005 section 3 (iii) any other person who practises a discipline or profession in the health area that involves the application of a body of learning. Substantive Equality Substantive equality recognises that: rights, entitlements, opportunities and access are not necessarily distributed equally throughout society equal or the same application of rules to unequal groups can have unequal results where service delivery agencies cater to the dominant, majority group, then people who are not part of the majority group and who have different needs might miss out on essential services. Hence, it may be necessary to provide different service types and approaches to people with disability and their families who are members of minority groups. Disability Services Commission Substantive Equality Statement of Commitment for People with Disabilities February 2006 For Further Information on Substitute Decision Making For Adults Contact: Office of the Public Advocate Level 1, 30 Terrace Road, East Perth WA 6004 PO Box 6293, East Perth WA 6892 Telephone:1300 858 455 Facsimile: (08) 9278 7333 Email: opa@justice.wa.gov.au Web: www.publicadvocate.wa.gov.au 16