Augmentative Communication in an Inclusive Preschool Setting

advertisement

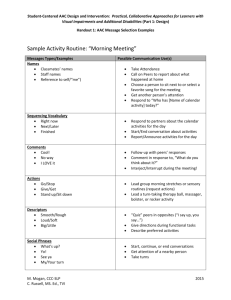

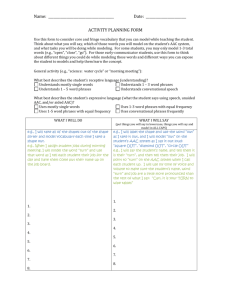

Augmentative Communication in an Inclusive Preschool Setting Summary – Early childhood education programs are often play-based and family-centered. Children gain knowledge through play in many areas including fine and gross motor, memory, attention, problem solving, pragmatic language, and expressive and receptive language. Early childhood special education programs share the play-based approach and are similar in many ways. These similarities are important as there is a push to educate young children with disabilities with those without. Bailey et al. found that all children benefit from an inclusive preschool program. Preschoolers with disabilities are able to observe and interact with typical peers while being exposed to a more challenging educational environment. Preschoolers without disabilities are able to learn about differences and acceptance. More importantly, friendships are formed among children with and without disabilities (Downing, 2002). Given the significant support for inclusion during early childhood education, there are now more preschoolers with disabilities attending school with their typical peers. Many preschool teachers have not had an opportunity or have had limited experiences teaching a student with a disability. These teachers need to receive extensive information regarding health issues, sensory needs, and assistive technology to name a few (Downing, 2002). Assistive technology (AT) is often an integral component in accessing the curriculum for students with a disability. AT specialists can aid in supporting the entire team. Sufficient support is crucial to facilitate the student’s success. The case study presented will discuss the various types of support provided by an AT specialist to a team working with a preschooler who uses an AAC device. This case study will focus on Xophia, a four year old female with autism and complex communication needs (CCN). Xophia was evaluated for an AAC system and received a high technology voice output communication device (Vantage Lite from Prentke Romich Company). She attends an inclusive preschool program and also receives after school speech and language services at a nearby clinic. Her support network includes her family, school team, and clinic speech-language therapist. Before receiving her communication device, Xophia primarily used picture symbols, minimal word approximations, and gestures to communication her wants and needs. Her receptive language skills were significantly higher than her expressive language skills. This is her first high technology augmentative communication device. It is also her family and school team’s first encounter with a high technology communication device. The school team was initially quite reluctant to use the AAC device and believed it to be too difficult for Xophia. Therefore, it was vital to offer immediate support to ease concerns and frustration. Formal trainings regarding the device were offered to the family, school team (teacher, paraprofessionals, speech-language pathologist), and clinic speech-language therapist. Trainings included instruction on basic hardware features and “how to” customizing and programming techniques as well as instruction on the language system. This included educating the team about icon features and functions and how to access the language. Perhaps most importantly, numerous trainings and meetings were devoted to strategies to teach and promote the use of Xophia’s AAC device. The goal of AAC is the most effective communication possible. A developmental language approach was selected to meet this goal. AAC device implementation was driven by strategies to facilitate independent and spontaneous novel utterances. An essential strategy for developing expressive language with a student who is new to an AAC system is aided language stimulation. Aided language stimulation occurs when the communication partner uses the student’s AAC system to communicate with him or her. This allows students with AAC systems to see the how they can initiate communication, make requests, share information, ask questions, and protest. Additionally, modeling the use of a student’s AAC system can reveal where the system may fall short of meeting their communication needs (Goosens’, Crain, & Elder, 1995). The team also benefited from learning various aspects of early language development. This included Brown’s Stages of Language Development (Brown, 1973) and examining toddler vocabulary frequency. Banajee, DiCarlo, & Stricklin (2003) analyzed the language samples of 50 toddlers to find predominately pronouns, verbs, prepositions, and demonstratives. These types of words are known as core vocabulary. Core vocabulary is a small set of words that are used frequently across environments. Baker & Hill (2000) found that 80% of what we say is communicated with only 200 core vocabulary words. This information was critical when selecting target vocabulary that would allow Xophia to formulate novel utterances. This case study is ongoing. Many other strategies will be discussed with Xophia’s team including incorporating communicative temptations, developing a prompting hierarchy, facilitating communication with peers and siblings, environmental engineering, and the importance of a manual communication board. Strategies to use in the home will also be shared with Xophia’s family. These items, as well as Xophia’s progress will be shared during the roundtable discussion. Ideally, AT specialists work closely and collaboratively with the entire team. AT specialists often provide ideas and accommodations; however it is up to the team to implement the recommendations. This roundtable discussion will allow for discussion regarding effective support strategies and the importance of a team approach. References Bailey, D.B., Jr., McWilliam, R.A., Buysse, V., & Wesley, P.W. (1998). Inclusion in the context of competing values in early childhood education. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13, 27-47. Benajee, M., Dicarlo, C., & Stricklin, B. (2003). Core vocabulary determination for toddlers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19, 67–73. Brown, R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. Downing, J. E. (2002). Including students with severe and multiple in typical classrooms. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. Goossens’, C., Crain, S., & Elder, P. (1995). Engineering the preschool environment for interactive, symbolic communication: An emphasis on the developmental period, 18 months to five years. Birmingham, AL: Southeast Augmentative Communication Conference Publications. Baker, B., Hill, K., & Devylder, R. (2000). Core Vocabulary is the same across environments. Paper presented at a meeting of the Technology and Persons with Disabilities Conference at California State University, Northridge.