Persian Dance Documentation - Northern Lights Arts and Sciences

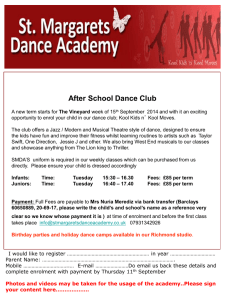

advertisement

Persian Dance Documentation

A Journey of Steps, Breaks, and Pauses

Baroness Ardenia ARuadh

(known in dance as Nadia)

Dance documentation is a challenge, of this there is no question. Dance is a

living, changing art form which is subject to interpretation of many kinds. As dance is

motion, it was not clearly “recorded” in ancient times. As an art of emotion, it seems to

defy clear and unquestionable written description.

Middle Eastern dance, in particular is hard to “document” clearly. We have many

visual examples of dance from Assyria, Egypt, Persia, and other places. These pictures

though, are static. They show “poses”, for lack of a better word. These poses may

truly be poses, or merely a moment which was a part of a fluid movement, which has

been frozen and captured by an artist. These pictures are also subject to artistic

interpretation and the socio-cultural mores of the time and culture in which they were

painted, sculpted, or carved. There are then further challenges of gaps in the history of

a dance or gaps in the historic evidence of dance.

Dance is a part of human nature and culture. People move to express emotion.

People move to release emotion. Music leads people to move, and to many it is a

seductive call that brings forth inspiration. There is dance in any culture where there is

music. Dance has meant different things to different cultures throughout time and

history. Dance was a way of communicating with the gods in many cultures. The

Guedra of Morrocco was and is still a dance to bring blessing to the dancer, the

audience, and the host. (Morrocco) Modern ballet is used to tell stories of love and

fantasy. Many other types of dance through the ages have been used to express the

secret fountains of the human existence. That people danced before the modern age

has never been questioned. The question asked about dance is not “If?” or “Why?”,

but “How?”

It might be suggested that the existence of modern dances from Middle Eastern

cultures proves the style of steps used in period dances. This is really not an accurate

interpretation, for many reasons. These reasons are related to time, travel, religion,

politics, and gender related issues.

A fairly accurate generality is that most Middle Eastern Dance, as performed in

the world today is conglomerate. There are styles with specific cultural influences, but

there has been much cross pollination of dance from one ethnic root to another.

Modern day Turkish dance is known for being flashy. Many describe modern Egyptian

dance as “cute” and stylized. American Tribal Style, which is a relatively new

conglomerate style, is often considered to be “earthy.” These dances may have their

own specific postures or names for movements, but many of the movements are the

same or slight variations of one another.

Religion has played a huge role in the spread and silencing of dance throughout

history, particularly, but not limited to Middle Eastern Dance. As religious policies and

regulations changed, dance was highlighted or driven underground. As various cultures

intermingled due to political change, dance forms changed. This will come further to

light in analyzing Persian dance in its similarity to Indian Temple Dance, and the ritual

dances of Asia. Especially in dealing with the Middle East, it is clear the ebb and flow of

religious zealousness and animosities helped to hasten or curtail the spread of dance

from one location to another. Teachers have lost students from a Middle Eastern dance

class because the students claimed that it was contrary to their Christian faith. Young

people may avoid the study of an eastern dance from because they have been told that

it is contrary to their faith. These are just a few points where religion, even now affects

the spread and interpretation of dance.

Politics may make the world go ‘round, but it has often impeded the growth and

recording of dance and its traditions. Some people in the Middle Eastern dance

community noted a temporary decline in new dancers following September 11, 2001.

Political changes in the Middle East in period regularly caused dance to be celebrated

or hidden. One particular example is found in Persia during the Safavid dynasty when a

group “fanatical Shiite dervishes” made Shiism the state religion of Iran and outlawed

music and dance. Many musicians, and possibly dancers fled the country for the

Moghul {sic} and Ottoman courts. (Friend) This leaves a gap of a significant period

when one tries to trace Persian dance from the 19th century into period. It does,

however leave open the possibility of Persian dance influencing what we now know of

dance in those cultures. These are just a few examples of how politic has influenced

the “archiving” of dance world wide, but specifically in the Middle East, and in reference

to Persia.

Gender is a key word when discussing Middle Eastern dance. Though we have

evidence of men’s dances like the Tatib in the post-period Middle East, as well as

documentation for a cultural history of men dancing, most people picture women when

speaking of Middle Eastern dance. I have heard it said that much of Middle Eastern

dance should be referred to as “women’s dance.” Many of the moves common to all

current Middle Eastern dance forms seem to have their roots in ancient birthing rituals

and prebirthing preparations. (Thabit) Other moves and stylings would be logical

“artistic” extensions of daily household tasks like bouncing a fussy child on one’s hip or

walking. As many cultures and faith throughout time have not recorded great details

about the lives of women, these kinds of facts are not clearly recorded. As some

cultures keep their women secluded, dance was never clearly recorded by an outsider.

As some cultures did no educate women, there was not always a way for women to

record their arts or daily lives.

Music is one last obstacle to approach before moving forward to analyze the

moves common in current Middle Eastern dance that do seem to be evidenced by the

miniatures painted in Persia during SCA period. Again, nothing was recorded. Music is

another living and dynamic art form. There is evidence of what instruments existed in

period. There are logical suppositions to be made about which instruments might have

been played together and how. This is thus, another pint of conjecture where fact and

logic hopefully collude. Without a clear understanding of what period music definitely

sounded like, one is still left to piece and guess how movement from one “pose”

depicted might move to another. Thus it is only possible to take the available evidence

and make an educated guess as to how dance might have been done in period.

As dance is not “completely” documented in its state of movement, it is

necessary to look at the depictions through a lens tinted by many factors. The first

factor is that Persian dance would be different in some ways from Modern Middle

Eastern dance due to some very specific facts about Persian culture. Some of these

fats are influenced by the location of Persia. Persian dance was also influenced by

costume, which was influenced by culture. Dance is also often influenced by the body

types common to the culture. This factor may be skewed, however, by the artistic

interpretations of the artists recording the depictions.

The Persian culture lens adds a very unique angle to any observation of dancers

from the miniatures. Persia can be considered the most “oriental” of the Middle Eastern

cultures in period. This is largely due to influences from Mongolia, as there were

periods where artists were “shipped” back and forth from one court to another due to

Mongol control of Persia (Farabi). There is also a clear cross-cultural influence from

India to Persia which is also evidenced by the miniatures. Indian dance has not

changed much over many years, and as a form of religious observance, it has been

much more accurately preserved and taught. Modern Persian dance has very stylized

hand positions and movements, which closely resemble those of modern and period

Indian temple dance. It may be possible to use traditional Central Asian and Uabek

dance techniques to fill in the holes from various period until now, as these cultures

already shared commonalities with Persia, but did not undergo the Shiite repression that

resulted in the loss of much of the history of dance in Persia (Friend) Using these ideas

as references when looking at the miniatures helps to create a frame in which to

analyze the movement indicated by the depictions.

Costume and body type also influence how the images of dancers should be

viewed. The fitting and layering of clothing from the period might make some of the

very large motions commonly seen in folkloric Egyptian or Lebanese dance somewhat

difficult. Most of the miniatures seem to depict people of a small to medium frame,

which is also somewhat different from the body type for the modern classical Middle

Eastern dancer in Lebanon. Large, exaggerated dance moves often look out of place

on dancers with small frames, especially while wearing very fitted and stylized clothing.

With these concepts in mind, an analysis of some of the pictures of dancers from the

Persian miniatures allows one to draw some logical conclusions about dance as it may

have been done in Persia in period.

Persian dance has been described as having small or minimal hip movement.

18th century Persian dance, as seen in the videos of Robyn friend shows small,

controlled hip movement. These movements are crisp and stylized. Figures 2-5 show

dancers with their feet fairly close together. Wide or accentuated hip movements

require a wider “base”. From the description, observation of modern Persian dance,

and logical understanding of dance kinesiology, the conclusion can be drawn that period

Persian dance involved small, clean hip motion. This type of motion is also the most

logical when one considers the fit of Persian garments in period, specifically the 15th

and 16th centuries.

The miniatures display feet part in various positions. This is logically in

indication of some potential for walking or movement. Those miniatures (figures 2-5)

which show an audience do not seem to show an overly large dance space, thus

indicating that movement might still be rather confined. This particular type of styling

would also follow some traditions in Indian and Central Asian dance. Some later period

Persian dances have more movement, but most seem to be performed in a fairly

confined space. Figure 4 shows a dancer with one foot raised. This can be interpreted

many ways. This could be a balance pose like those found in some Indian dances.

This could be a frozen moment in a zanuba or karshlama step, which is a common

move in Turkish and Egyptian dance where the dancer steps forward on one foot, shifts

his/her weight back to center on the other foot, steps back and the re-shifts his/her

weight back to center, somewhat like a classical salsa step. This dancer depicted could

also be preparing to turn. All of the moves are logical choices when one examines the

miniatures, in light of the other factors previously discussed.

Arm positions are very clear in the miniatures, which gives a dancer many

options. In figure 4 the right arm is clearly raised and bent at the elbow with a stylized

hand. This part of the pose is somewhat reminiscent of the carvings from Egypt which

are modeled into the Pharonic style. The left arm is also bent or curved at the elbow,

but is then brought in towards the hip. This may be an indication that the dancer was

performing what is modernly know as a snake or serpent arm where the dancer moves

both arms up and down in opposite serpentine motions rolling from the shoulder,

thought the elbow, through the writs and finishing with the fingertips with one arm

reaching the apex while the other is at its lowest point. Figure 1 shows a seated

woman who may be a dancer. Her left arm is in a similar pose to that of the dancer in

figure 4. Her right arm however is near her “heart. This could be a gesture of “giving”

which is common in post-period forms of Middle Eastern dance, including Persian.

Figure 2 shows two dancers. The dancer to the right has both arms upraised, possibly

in a gesture of “supplication”. This move is also similar to those found in traditional

Egyptian Pharonic styling. Similar poses to this are also included in traditional Indian

dance. This arm pose is often seen in post-period dance accompanied by sharp,

accented head slides. The dancer in figure 3 has similar arm position to the dancer on

the left of figure 2 and the dancers in figures 4 and 5. An interesting note is that the

dancers in figures 2-5 all may have some sort of small scarf in each hand (these may

also be extensions of their sleeves). Though it does not appear that veil as used in

modern Middle Eastern dance is period, these small scarves may be forerunners.

There is a 20th century Persian/Iranian dance from the Qashqa’i people that is

performed using a small hand scarf in each hand. These scarves may also be a

glimpse into the history of this dance style.

Dance is a dynamic art. It cannot truly be captured without motion. It is a fact

that people in period danced. There are pictures. There are tales. It is left to the

dancer and the musician to guess how the music was played and how it was

interpreted. We have images that are frozen moments of dance. These images can

only be used as guides. When the images come together with knowledge of other

styles contemporary to the miniatures and knowledge of dance from the culture in post

period, there is the most potential for a more accurate re-creation of dance in period.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Notes on references:

Many of my comments have come directly from my own observations as a

student of various dance forms. Other have come from discussion with and lessons

from noted artists like Lady Kate the Wench, Mistress Su’ad al Raksa, Morrocco, Robyn

Friend , Mistress Roxane Farabi, Mistress Safia Al Khansaa, Master Twit Ullium of

Witlow, Mistress Morgen Duval, Mistress Lakshmi Aman., and Mistress Anne Elaina of

Riversbend. When I remember specifically where a comment came from, I have noted

it.

I would like to thank all of the above people for their time, lessons, encouragement, and

opinions.

Thabit, Alia. St. Johnsbury, VT. A brochure promoting her classes and giving a brief

history of Middle Eastern Dance.

Friend, Robyn, Phd. Dances of Iran. 2000. and e-mail discussions relevant to the

documentation of Persian dance pre-1620.

Farabi, Roxane. 2003 Documentation for Persian patterns, also verbal history lessons

on Persian history, culture and customs.

Morrocco. Classes on the Guedra and Middle Easter Dance in General 2001, 2004.

Also for her web article on the guedra.

Figure 1

Khusraw & Shirin Entertained by Dancers

1568

(Source unknown, I copied the picture from Mistress Roxane’s clothing documentation)

Figure 2

Kanifu before Iskandar

1450

Figure 3

Dolvarani and Khirzkhan

Miniatures Illuminations of Amir Hosorv Dehlevi’s Works

Fan. Uzbek SSR. 1983

Figure 4

Binding of the Divan…

1540

Skira. Hunt for Paradise Coutrs of Safavid Iran.

Skira Editore , Milan 2003.

Figure 5

Timur holds a great feast with Amir Husayn …

1552

Sims, Eleanor. Peerless Images Persian Painting and its Sources.

Yale University Press. Singapore 2002.