schooling mandated

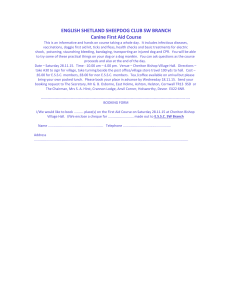

advertisement