POETRYHandout

advertisement

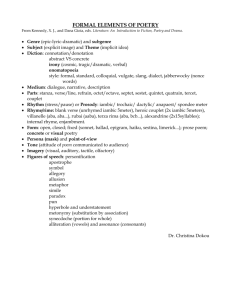

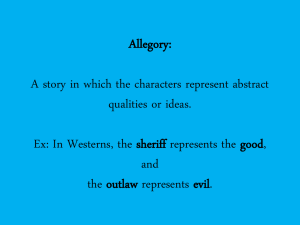

Poetry (Handout by Natália Pikli) A poem= specially patterned text, to express with language what cannot be expressed by using ordinary, everyday language => form and content are interrelated, in strong relation with each other Types of poetry: 1. narrative poetry (telling a story) genres: the epic, the ballad, the romance 2. lyric poetry (emotional, philosophical response to the world) genres: the song, the ode, the hymn, the elegy, the sonnet What makes a poem? 1. Music (lyric<lyre, ancient poems were sung, dance/music/poetry) - rhythm - metre - rhyme - alliteration (‘head rhyme’ – matching initial consonants) - sound associations (harmonious, disharmonious) 2. Imagery (figurative language and tropes) - metaphor (identification; subject/tenor/ & figurative term /vehicle/) (conceit: complex, far-fetched metaphor, unlikely , unexpected connections) - simile (like, as) - personification (inanimate → attributes of the animate) - oxymoron (a paradox in a metaphor, “irreligious piety”) - metonymy (an attribute/a part of the thing is substituted for the thing itself /pars pro toto/ synecdoche/, based not on similarity but association/relation/connection) - synesthesia - allegory - symbol 3. Poetic diction (language) - archaism or/and coining new words, phrases - parallels and contrasts, ambiguity, paradox - repetition (repetition with variation= incremental repetition) → rhythm - special word order (eg. inversion) 4. A personal impersonal attitude to the world (persona) (cf. dramatic monologue) Metre, rhyme and verse form Metre: the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry (regular rise and fall) – gives the underlying rhythm of a poem Most common from the early Renaissance in English poetry: STRESS-SYLLABLE METRE (also called accentual-syllabic metre) (1. pure syllabic/quantitative metre is very rare = Hungarian, Greco-Roman ‘időmértékes’ metre 2. Old English poetry and medieval alliterative poetry, nursery rhymes: PURE STRESS METRE/ACCENTUAL VERSE: only stress matters, syllables do not = strong-stress metre, always four stresses in a line, cf. Baa baa black sheep) a little unit of syllables (at least one stressed ΄ BEAT and one or more unstressed ˇ OFFBEAT ) = a foot Most common metrical feet : the iamb (ˇ ΄), iambic foot eg. behind the trochee (΄ ˇ), trochaic foot eg. rabbit the spondee (΄ ΄), spondaic foot eg. Dark, dark the anapaest (ˇ ˇ ΄), anapaestic foot eg. understand the dactyl (΄ ˇ ˇ), dactylic foot, eg. agitate “Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time” LINES: dimeter (two feet, eg. chimney sweeper = trochaic dimeter), trimeter (3), tetrameter (4), pentameter (5), hexameter (6) (iambic hexameter= alexandrine) caesura: a pause in a line of poetry end-stopped lines: a pause at the end of a line (marked by punctuation) run-on lines (enjambement) VERSE FORMS/STANZAS: heroic couplet (rhymed iambic pentameter) triplet/tercet (three lines with a single rhyme) quatrain (a four-line stanza) ballad metre (4 lines, xaxa, iambic tetra- and trimetre, in Hungarian lit. called ‘Scottish balladform’ A walesi bárdok, Szózat) rhyme royal (a seven-line stanza in iambic pentameter rhyming ababbcc) octava rima (an eight-line stanza rhyming abababcc) Spenserian stanza (a nine-line stanza rhyming ababbcbcc, 8x iambic pentameter + an alexandrine) blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter, Shakespeare’s and Marlowe’s plays) sonnet 1. Petrarchan/Italian : 4 stanzas of 4+4+3+3 lines (an octave+a sestet) abba abba cde cde (or any other variation of 8+6 rhyming scheme) 2. Shakespearean/English: 4+4+4+2 lines (three quatrains and a couplet) abbacddceffegg in iambic pentameter RHYMES: rhyme pattern/scheme - assonance (repetition of vowel sounds) vs perfect rhyme: last stressed V + all following sounds match - end/tail rhyme - internal rhyme - masculine (strong) rhyme: a single stressed syllable – “hill” and “still” (or, the last syllable is rhyming and stressed) - feminine (weak) rhyme: two rhyming syllables, one stressed, the other unstressed – “hollow” and “follow” - eye rhyme: spelt alike but not rhyming – “love” and “prove” - imperfect/slant/oblique rhyme: do not quite rhyme – “soul” and “wall” - sprung/half-rhyme (consonance, matching consonants) “groaned” and “groined” - holorhyme – identical rhyme (fun) ‘For I scream/ for ice cream’ A possible method to approach a poem (Help with Poems 101) 1. Read the poem several times (let it flow through your soul/mind, evoking thoughts and emotions) 2. Try to define the basic problems/questions/ideas/emotions the poem brings up. (Help: search for basic contrasts) 3. See how the form, the patterning of the language contributes to and supports the main problems/emotions. Search for the non-literal, the out-of-the-ordinary – circle/underline it Point to a detail, and justify its presence: why is it there, how does it relate to the main questions. Say how the different poetic means express what is behind/between the lines – - title: how does it relate to the poem - the general atmosphere evoked - look for structuring thoughts/impressions: basic contrasts, parallels - poetic means: what do rhymes/alliterations/assonance connect how rhythm/metre/repetitions contribute to the thoughts/emotions images: what kind of tropes, what do they highlight, what do they call attention to - use direct quotes to pinpoint important ideas in your analysis, but keep the balance (it’s not “a book of aphorisms”) 4. Put the poem into a larger context; you might relate it - to other works by the author - to other works of the era/national poetry/international poetry - to certain archetypes, or other concepts out of the strictly literary "Daffodils" (1804) I WANDER'D lonely as a cloud That floats on high o'er vales and hills, When all at once I saw a crowd, A host, of golden daffodils; Beside the lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze. Continuous as the stars that shine And twinkle on the Milky Way, They stretch'd in never-ending line Along the margin of a bay: Ten thousand saw I at a glance, Tossing their heads in sprightly dance. The waves beside them danced; but they Out-did the sparkling waves in glee: A poet could not but be gay, In such a jocund company: I gazed -- and gazed -- but little thought What wealth the show to me had brought: For oft, when on my couch I lie In vacant or in pensive mood, They flash upon that inward eye Which is the bliss of solitude; And then my heart with pleasure fills, And dances with the daffodils. By William Wordsworth (1770-1850). The Journey of the Magi By T.S. Eliot "A cold coming we had of it, Just the worst time of the year For a journey, and such a long journey: The was deep and the weather sharp, The very dead of winter." And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory, Lying down in the melting snow. There were times we regretted The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces, And the silken girls bringing sherbet. Then the camel men cursing and grumbling And running away, and wanting their liquor and women, And the night-fires gong out, and the lack of shelters, And the cities hostile and the towns unfriendly And the villages dirty, and charging high prices.: A hard time we had of it. At the end we preferred to travel all night, Sleeping in snatches, With the voices singing in our ears, saying That this was all folly. Then at dawn we came down to a temperate valley, Wet, below the snow line, smelling of vegetation; With a running stream and a water-mill beating the darkness, And three trees on the low sky, And an old white horse galloped away in the meadow. Then we came to a tavern with vine-leaves over the lintel, Six hands at an open door dicing for pieces of silver, And feet kicking the empty wine-skins. But there was no information, and so we continued And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory. All this was a long time ago, I remember, And I would do it again, but set down This set down This: were we lead all that way for Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly, We had evidence and no doubt. I have seen birth and death, But had thought they were different; this Birth was Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death. We returned to our places, these Kingdoms, But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation, With an alien people clutching their gods. I should be glad of another death. Preludes by: T. S. Eliot (1888-1965) I The winter evening settles down With smell of steaks in passageways. Six o'clock. The burnt-out ends of smoky days. And now a gusty shower wraps The grimy scraps Of withered leaves about your feet And newspapers from vacant lots; The showers beat On broken blinds and chimney-pots, And at the corner of the street A lonely cab-horse steams and stamps. And then the lighting of the lamps. II The morning comes to consciousness Of faint stale smells of beer From the sawdust-trampled street With all its muddy feet that press To early coffee-stands. With the other masquerades That time resumes, One thinks of all the hands That are raising dingy shades In a thousand furnished rooms. III You tossed a blanket from the bed, You lay upon your back, and waited; You dozed, and watched the night revealing The thousand sordid images Of which your soul was constituted; They flickered against the ceiling. And when all the world came back And the light crept up between the shutters, And you heard the sparrows in the gutters, You had such a vision of the street As the street hardly understands; Sitting along the bed's edge, where You curled the papers from your hair, Or clasped the yellow soles of feet In the palms of both soiled hands. IV His soul stretched tight across the skies That fade behind a city block, Or trampled by insistent feet At four and five and six o'clock; And short square fingers stuffing pipes, And evening newspapers, and eyes Assured of certain certainties, The conscience of a blackened street Impatient to assume the world. I am moved by fancies that are curled Around these images, and cling: The notion of some infinitely gentle Infinitely suffering thing. Wipe your hand across your mouth, and laugh; The worlds revolve like ancient women Gathering fuel in vacant lots.