handout 1 POETRY (written by Natália Pikli)

advertisement

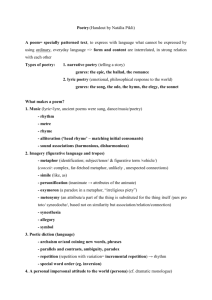

1 POETRY – handout by Pikli Natália – A poem= specially patterned text, to express with language what cannot be expressed by using ordinary, everyday language => form and content are interrelated, in strong relation with each other Types of poetry: 1. narrative poetry (telling a story) genres: the epic, the ballad, the romance 2. lyric poetry (emotional, philosophical response to the world) genres: the song, the ode, the hymn, the elegy, the sonnet What makes a poem? 1. Music (lyric<lyre, ancient poems were sung, dance/music/poetry) - rhythm - metre - rhyme - alliteration (‘head rhyme’ – matching initial consonants) - sound associations (harmonious, disharmonious) 2. Imagery (figurative language and tropes) - metaphor (identification; subject/tenor/ & figurative term /vehicle/) (conceit: complex, far-fetched metaphor, unlikely , unexpected connections) - simile (like, as) - personification (inanimate → attributes of the animate) - oxymoron (a paradox in a metaphor, “irreligious piety”) - metonymy (an attribute/a part of the thing is substituted for the thing itself /pars pro toto/ synecdoche/, based not on similarity but association/relation/connection) - synesthesia - allegory - symbol 2 3. Poetic diction (language) - archaism or/and coining new words, phrases - parallels and contrasts, ambiguity, paradox - repetition (repetition with variation= incremental repetition) → rhythm - special word order (eg. inversion) 4. A personal impersonal attitude to the world (persona) (cf. dramatic monologue) Metre, rhyme and verse form Metre: the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry (regular rise and fall) – gives the underlying rhythm of a poem Most common from the early Renaissance in English poetry: STRESS-SYLLABLE METRE (also called accentual-syllabic metre) (1. pure syllabic/quantitative metre is very rare = Hungarian, Greco-Roman ‘időmértékes’ metre 2. Old English poetry and medieval alliterative poetry, nursery rhymes: PURE STRESS METRE/ACCENTUAL VERSE: only stress matters, syllables do not = strong-stress metre, always four stresses in a line, cf. Baa baa black sheep) a little unit of syllables (at least one stressed ΄ BEAT and one or more unstressed ˇ OFF-BEAT ) = a foot Most common metrical feet : the iamb (ˇ ΄), iambic foot eg. behind the trochee (΄ ˇ), trochaic foot eg. rabbit the spondee (΄ ΄), spondaic foot eg. Dark, dark the anapaest (ˇ ˇ ΄), anapaestic foot eg. understand the dactyl (΄ ˇ ˇ), dactylic foot, eg. agitate “Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time” 3 LINES: dimeter (two feet, eg. chimney sweeper = trochaic dimeter), trimeter (3), tetrameter (4), pentameter (5), hexameter (6) (iambic hexameter= alexandrine) caesura: a pause in a line of poetry end-stopped lines: a pause at the end of a line (marked by punctuation) run-on lines (enjambement) VERSE FORMS/STANZAS: heroic couplet (rhymed iambic pentameter) triplet/tercet (three lines with a single rhyme) quatrain (a four-line stanza) ballad metre (4 lines, xaxa, iambic tetra- and trimetre, in Hungarian lit. called ‘Scottish balladform’ A walesi bárdok, Szózat) rhyme royal (a seven-line stanza in iambic pentameter rhyming ababbcc) octava rima (an eight-line stanza rhyming abababcc) Spenserian stanza (a nine-line stanza rhyming ababbcbcc, 8x iambic pentameter + an alexandrine) blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter, Shakespeare’s and Marlowe’s plays) sonnet 1. Petrarchan/Italian : 4 stanzas of 4+4+3+3 lines (an octave+a sestet) abba abba cde cde (or any other variation of 8+6 rhyming scheme) 2. Shakespearean/English: 4+4+4+2 lines (three quatrains and a couplet) abbacddceffegg in iambic pentameter RHYMES: rhyme pattern/scheme - assonance (repetition of vowel sounds) vs perfect rhyme: last stressed V + all following sounds match - end/tail rhyme - internal rhyme - masculine (strong) rhyme: a single stressed syllable – “hill” and “still” (or, the last syllable is rhyming and stressed) 4 - feminine (weak) rhyme: two rhyming syllables, one stressed, the other unstressed – “hollow” and “follow” - eye rhyme: spelt alike but not rhyming – “love” and “prove” - imperfect/slant/oblique rhyme: do not quite rhyme – “soul” and “wall” - sprung/half-rhyme (consonance, matching consonants) “groaned” and “groined” - holorhyme – identical rhyme (fun) ‘For I scream/ for ice cream’ A possible method to approach a poem (Help with Poems 101) 1. Read the poem several times (let it flow through your soul/mind, evoking thoughts and emotions) 2. Try to define the basic problems/questions/ideas/emotions the poem brings up. (Help: search for basic contrasts) 3. See how the form, the patterning of the language contributes to and supports the main problems/emotions. Search for the non-literal, the out-of-the-ordinary – circle/underline it Point to a detail, and justify its presence: why is it there, how does it relate to the main questions. Say how the different poetic means express what is behind/between the lines – - title: how does it relate to the poem - the general atmosphere evoked - look for structuring thoughts/impressions: basic contrasts, parallels - poetic means: what do rhymes/alliterations/assonance connect how rhythm/metre/repetitions contribute to the thoughts/emotions images: what kind of tropes, what do they highlight, what do they call attention to - use direct quotes to pinpoint important ideas in your analysis, but keep the balance (it’s not “a book of aphorisms”) 4. Put the poem into a larger context; you might relate it - to other works by the author - to other works of the era/national poetry/international poetry - to certain archetypes, or other concepts out of the strictly literary