Independent Concentration Proposal

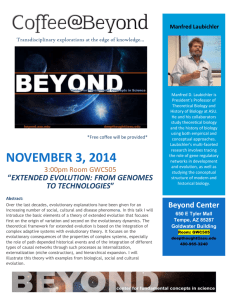

advertisement

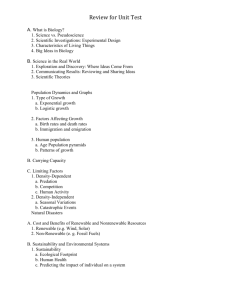

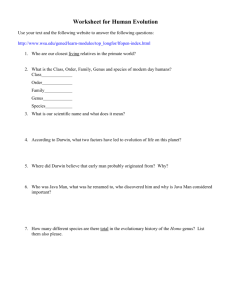

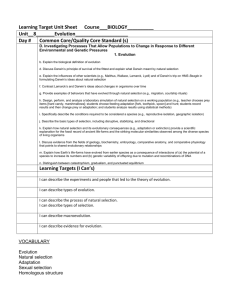

Lavinghouse 1 Proposal for an Independent Concentration Program In the The Development of Science Submitted by: Shoshana Lavinghouse, in her fourth semester SISD23591 Box 0761 (401) 867-6867 Candidate for Bachelor of Arts degree, with honors Class of 2006 This is the second submission, and will replace no previously declared program Faculty Sponsor: Joan Richards Professor of History Lavinghouse 2 Concentration Proposal I vividly recall an intellectual challenge posed to my classmates and me in high school. This took us by surprise; the answer appeared obvious, but the obvious answer was incorrect. The challenge was “define the humanities.” As our school had blocked off two periods for this subject, one taught by our English teacher and the other by our history teacher, we responded that the humanities were literature, grammar, and history. Our puzzled frowns deepened when our teacher encouraged a more complete answer. Surely we had provided all the components of the field. In fact, we had not. The missing part, it turned out, was science. Referencing the early modern definition, my teacher proposed that science, literature, history and philosophy should be defined under the umbrella term “humanities.” The connection that I failed to make on that day between science and the humanities is one that I would like to fully comprehend now, in an institution in which I have all the tools at my disposal to do so. In particular, I would like to ascertain how science emerged as a special way of approaching the natural world. Under the old system, knowledge was largely derived from existing classical and biblical sources. When the causes of natural phenomena could not be readily established with human senses, scholars relied on hidden forces attributable to god or an equally powerful force to explain them. Such explanations satisfied the small scholarly community of the middle ages, which extended to monks and aristocrats educated in universities or monastic schools. Both groups shared a reliance on erudition rather than experience for their knowledge, since honor precluded the elite from involving themselves with manual labor. Lavinghouse 3 This did not stop the accumulation of observations that increasingly challenged preexisting notions. Advances made in navigation and astronomy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries made scholars more willing to employ new methods to preexisting problems. The seventeenth century saw the emergence of a movement that relied less on occult explanations, finding ways to explain all natural phenomena. Led by the synthesis of Francis Bacon, members of the Royal Society in England presented a socially verifiable system of establishing truth. Such leaders as Robert Boyle firmly held that to establish truth, or to create a fact, one must experiment with a hypothesis in the presence of qualified witnesses. This departed from the old system’s disregard for witnessing; their standards only desired that the argument make logical sense. However, Boyle would not have just anyone serve as a qualified witness. Qualified meant trustworthy, and trustworthy meant gentlemen. Gentleman advantageously bound themselves with a strict code of honor that would preclude fraud. Furthermore, experiments needed to be structured such that they could potentially be proven wrong if repeated. In sum, the Royal Society desired facts to be constructed through falsifiable experiments presented to qualified witnesses, who could then repeat it and produce the same result. The Royal Society’s standards appear familiar to the modern reader. Indeed, we cherish the standard of establishing facts by reproducible and falsifiable experiments. To fit a less hierarchical society and experiments that increasingly require more time to produce significant results, the modern age has added a few requirements. The procedure has brought experiments into private spaces, and emphasized presenting the procedure and results through indirect mediums, in particular scholarly journals. As a means of establishing certainty without direct audiences, these journals employ peer review. This Lavinghouse 4 involves a panel of people reputable for their education and work in the field who critique articles before the journal publishes them. In a sense this fosters the perspective of scientists as people separate from society, as their predecessors were. However, education has replaced social status as the dividing factor between scientists and the rest of society. As such, scientists have come to rely on outside funding to support their research. The increased pressure of finding funding underlies the importance of peer review, since modern scientists largely cannot fund themselves nor fall back on the gentlemanly standard of the seventeenth century. However, as the recent debate over global warming has shown, peer review can easily be attacked. Whose money is accepted, and to what extent that source appears to profit by the results, often produces challenges of biased, and therefore illegitimate science. When to accept authority thus provides a challenge to the distinction between legitimate and illegitimate science. The skepticism underlying the scientific process since it was first extended to the public serves both to buttress and undermine the method. Despite this, we expect scientific results released to the public through peer reviewed journals, based on falsifiable and repeatable experiments. Through my concentration, I will trace the changes in scientific epistemology and methodology through European history from the end of the middle ages to the present. My program’s reliance on courses in history and philosophy reflect my general desire to approach this subject as a historian. However, it is insufficient to simply talk about science. In a reflection of the modern emphasis on learning through experience, my studies must also include scientific methodology. I will attain this within the field of evolutionary and vertebrate biology. In particular, I seek to find the causes and extent of the removal of theological and mystical elements from biological investigations of life’s Lavinghouse 5 origins and history. In the process I will investigate the relationship between religion and philosophy, and the extent to which these fields persist in science. Evolutionary biology provides a model framework for this study. It reveals the tensions between a religious and secular mindset, as well as the range of interpretations that an experiment or a theory can engender. Furthermore, Charles Darwin represents a noteworthy study in the human effort involved in science. His struggle over whether or not to publish his theory reveals the larger reluctance of most key figures to radically depart from accepted norms. In a broader sense, evolution also represents a reflection of how modern science developed. As a nascent field, evolution had to rely on occult causes as explanations. The ease of attacking evolution reduced when Mendelian genetics added a testing means with measurable results within the lifetimes of experimenters. Thus both the path to the theory’s introduction and its establishment reveal the broader evolution of science from a field of natural philosophy to the established means of producing data. The interdisciplinary nature of this course of study precludes my entrance into established concentration programs at Brown. Should I do so, I would lose out on aspects of the other programs that I feel would expand my understanding. Science and history have different methods of investigating the world; the former through an ethos that values collaborative efforts to establish objectivity and precision, the latter through an ethos that values scholarship through which individuals seek to explain social phenomena. Gray areas exist in between the two; and I want to explore them. Historians and philosophers are the ones who practice this, so I must study them both. Study abroad at a university with a strong program in the history of science will allow me tap into this international community. The programs at the University of Melbourne and the University of New Lavinghouse 6 South Wales fit the bill. In particular I believe the courses on evolution and philosophy of science will advance my thesis work. Due to the nature of my schedule as outlined in the following course list, I will be applying for the fall semester of this year. The applications for both programs are due by March 15, and I expect to hear back from them in late April or early May. I will notify the committee should I be accepted to and decide to attend one of these programs. In sum, through my proposed concentration in the development of science, I will study biology, history, and philosophy in order to gain an understanding of how certainty is formed and the ways we delineate the boundaries of science. Lavinghouse 7 Annotated Course List Core Classes: Science: BI 32- Vertebrate Embryology- This perspective on embryology mixes scientific methodology and social context. In addition, it will provide perspective on the creationist-evolutionist debate. It will introduce me to modern methods of scientific research in contrast with the old, and emphasize advances in technology that permitted these changes. BI 48- Evolutionary Biology- Introduces the mainstream view of how nature operates on organisms. Furthermore, the analysis of the facts through discussion of scientific papers produces a knowledge of how scientists present their findings to other scientists in addition to enriching the discussion of the theories and techniques employed. CG 32- The Biology and Evolution of Language- Through comparisons of the biology of speech in humans, chimpanzees, and Neanderthals, this course presented evolution and an insight into the debates among cognitive scientists’ methodology. Humanities and Social Sciences: CL 112 sec.2- Myth and the Origins of Science- This course examines the legacy of ancient scientific thought through the writings of various authors on human and cosmic origins in literary, philosophical, and scientific texts. I will attain a firmer foundation in my studies through this investigation of ancient science, scholarly pursuits that still underlie our modern studies. EL 190 sec. 7- Twentieth Century Reconceptions of Knowledge and ScienceProvides an expansion of the study of modern science studies by delving into “critiques of classic and prevailing (rationalist, realist, positivist) ideas of scientific truth, method, objectivity, and progress and the development of alternative (constructivist, pragmatist, historicist, sociological) accounts; the dynamics of knowledge; the relation between scientific and other cultural practices.” Exposure to science writers not covered in UC49 through the work of Fleck, Foucault, Rorty, and Latour. HI 97 sec.6- Magic, Science and Religion in Early Modern Europe- The course provides a greater insight into the interrelations of the three terms, particularly in its approach to the occult activities as legitimate. This introduces the main ideological differences between modern and early modern thinkers, namely that the increased availability of facts led the elite to specialize in a way that prevented the existence of Renaissance men. HI 118- The Rise of the Scientific Worldview- Provides more foundation work in the European mindset of the early modern period, this time by focusing on the natural philosophers that have been attributed with the advances that led to modern science. This further emphasized the problems of the transmission of ancient learning and which contributed to the practice of science. Lavinghouse 8 HI 119- Nineteenth Century Roots of Modern Science- Despite the name, the course focuses on the period from the enlightenment to Einstein, making two important contributions to my studies. It provides a connection between my studies of early modern and modern science, as well as background into the age in which evolutionary theory grew. HI 197 sec.34- Knowing and Believing: Galileo-Darwin- The course bridges the gap between the scientific revolution and the nineteenth century, providing continuity and the Enlightenment to my studies. In particular, the analysis of the interaction between religious and scientific outlooks and institutions directly pertains to my studies. Furthermore, it will help cement my knowledge of the period. PB160 sec.1- On the Dawn of Modernity- Provides the perspective of Portuguese exploration as the basis for studying the rise of a scientific, quantitative worldview from the classical, qualitative worldview in Europe. The course includes an introduction to Greco-Roman science and a treatment of the relationship between science, technology and theology in medieval Europe. PL 21- Science, Perception and Reality- Treats the clash of scientific logic and commonsense and responses to the problems they raise. PL175- Epistemology- This course covers the study of thought. Its study of skepticism, knowledge and its relation to thought, subjectivity and objectivity, and the epistemology of the social sciences will provide a way of framing my understanding. Furthermore, this course will incorporate early modern thinkers, which will help me to cement my understanding of their perspectives and knowledge. UC 49- Introduction to Science Studies- This course investigates how society interacts with science. Some of the most salient features are the treatment of words such as “certainty” and “truth,” as well as the role of scientists in the present. Related Courses: BI 20- The Foundations of Living Systems- An overview of most topics in modern biology, including evolution and sociology was presented in this course. Thus it provides a stepping stone for my study of biology. GE 1- The Face of the Earth- The study of geology introduced. This course further provided a prospective on how and why people believe the earth has changed over time. In this way the study of the earth mirrors the study of evolution on an inanimate scale. EL 119 sec. 2- Science as Writing, Science as Writer- Exploring the production of science writing, allowing me to focus on how science is communicated. Lavinghouse 9 HI 197 sec.31- Religion and Secularization in the West- Explores the transformation of organized religion’s role in Europe and America from the middle ages to the present. The focus on the relationship between reason and revelation in learned culture and popular religious practice will provide a basis for understanding the rise of evolution. UC 44- Recovering the Past- Inquiry into our basic assumptions of the historical sciences and the role of science in modern culture. UC 152- The Shaping of Worldviews- Examines how ideologies and beliefs are formed. This will allow me to review my knowledge of rationality and philosophy and test them against the diversity of worldviews. Course Order: Fall 2002 CG32- The Biology and Evolution of Language PB160 sec.1- On the Dawn of Modernity Spring 2003 BI20-The Foundations of Living Systems GE1-The Face of the Earth HI97 sec.6-Magic, Science and Religion in Early Modern Europe Fall 2003 BI48- Evolutionary Biology HI118- The Rise of the Scientific Worldview UC49-Introduction to Science Studies Spring 2004 BI32- Vertebrate Embryology EL119 sec.2 Science as Writing, Science as Writer HI119- Nineteenth Century Roots of Modern Science CL112 sec. 2- Myths and the Origin of Science Fall 2004 Likely Study Abroad (final details will be divulged when they become available) Spring 2005 HI197 sec.34- Knowing and Believing: Galileo-Darwin PL175- Epistemology UC44- Recovering the Past Fall 2005 EL190 sec. 7-Twentieth Century Reconceptions of Knowledge and Science Thesis writing Spring 2006 UC152- The Shaping of Worldviews PL 21- Science, Perception and Reality HI197 sec.31- Religion and Secularization Thesis Writing Lavinghouse 10 Final project The focus of my concentration has been the evolution of modern science from the Renaissance to the present, as it transformed from a branch of the humanities to an autonomous, powerful field. The development of evolutionary theory and the ongoing debate between evolution and creation covers the themes that arise within my general study. Evolution’s development as a field of science contains the simultaneous struggle for legitimacy, certainty and a place with god, thus making it a nice capstone for my studies. The movement to explain the history of life on earth as separate from the story detailed in Genesis flowered at the end of the Enlightenment, following two centuries of intellectual change in Europe. This change had pulled the practice of natural philosophy from theology’s handmaiden to a legitimate practice of its own. However, its autonomy did not mean a loss of religious ties. In fact, not until the Enlightenment would the kind of skepticism that Descartes had fostered in seeking knowledge translate into a rejection of god in scientific theory, which quickly became stigmatized. While total rejection of god hovered at the fringe, men tinkered with how much of scripture was actually true. The standard story of the Earth’s origins upheld by all “good Christians” clearly had some faults. The Bible failed to demonstrate the Earth’s age, and estimates varied. Furthermore, men found bones that belonged to no known creature. Many claimed that these were the remains from Noah’s flood. However, men like Erasmus Darwin, Georges Cuvier, and Charles Lyell would take a different approach. By extending the age of the earth to beyond the history of man, these men introduced the idea of geologic time, and animals that became extinct and evolved from a common Lavinghouse 11 ancestor. These early views would appear in Charles Darwin’s more developed concept of the evolution of species. They would also set the debate for how much of scripture could be culled out as metaphor, and how much of it was actually true. One of the many problems with dethroning the Bible was the certainty and legitimacy vacuum it would leave. If your theory didn’t have god backing it up, what else could give it the credibility and certainty to be accepted? Natural philosophers had been working on this problem since the seventeenth century. Their solution made legitimacy and certainty contingent upon good character in addition to reproducible and falsifiable experiments. Given this background, Darwin’s story appears all the more powerful. He struggled with legitimizing a theory that challenged the prevailing view on the origin of species, and in his own uncertainty held it down until another man produced the same theory. He stockpiled evidence in his study of Galapagos finches, domestic pigeons and other studies, and struggled to present his idea as clearly and fully as possible. He organizes his work as a large tome, attempting to clearly explain each point of his theory. When Darwin finally published, the theory of evolution became the counter to the creation story of Genesis, thereafter the Creation theory. From its founding, the followers of Creationism have questioned both evolution’s acceptance of god and its legitimacy. The debate between the two has accentuated Creationism’s nonscientific status from the evolutionists’ perspective, while Creationists condemn evolution as a threat to a healthy social environment. My project will reveal how evolutionary arguments against Creationism microscopically reflect the modern definition of science. Lavinghouse 12 Bibliography The Theory Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of Species- A Facsimile of the First Edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964. *The original statement of evolutionary theory. A close reading provides a way of comparing the modern arguments, in addition to ascertaining the accuracy of Creationist counterarguments. Freeman, Scott and Hebron, Jon C. Evolutionary Analysis, Third Edition. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2003. *This modern textbook in evolution provides information on current methodology, with diagrams and case studies. The Evolution of the Theory Caudill, Edward. Darwin in the Press: The Evolution of an Idea. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, Inc., 1989. *As the press is our main means of obtaining and synthesizing information, this book presents an excellent way of following the evolutionary debate. It presents the story of evolution to the 1980s, including the rise of Social Darwinism, Creationism, and the defenses for evolution. Dobzhansky, Theodosius; Ayala; Stebbins; and Valentine. Evolution. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1977. *This book nicely incorporates all the directions that evolution had gone in up to its publication in 1977. This includes genetics, speciation, the future of evolution as it relates to mankind, artificial evolutionary control, philosophical issues in studying science and the evolution of the following: the universe, prokaryotes and singe celled eukaryotes, metazoa and humans. Mayr. One Long Argument: Charles Darwin and the Genesis of Modern Evolutionary Thought. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991. *Mayr covers the history of evolution from Darwin to the modern day. He begins with an analysis of how Darwin developed his theory, the situation surrounding its publication, and its modern refinements. He concludes with his interpretation of where evolution’s next frontier, which he perceives as the “elucidation of the structure of the genotype and the role of development.” (157) Secord, James A. Victorian Sensation : The Extraordinary Publication, Reception, and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001. *This book chronicles the publication and reception of the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, a book that used evolutionary terms to describe the creation of the universe and human destiny. This is noteworthy, since the book was published in 1844before The Origin of Species. Furthermore, it elicited all of the negative theological attention that would dog Darwin’s theory; indeed, Darwin read this work while in a quandary over whether or not to publish his own theory. Lavinghouse 13 Creationism and God’s Place in Evolution Numbers, Ronald. The Creationists: The Evolution of Scientific Creationism. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1992. As the title implies, Numbers follows the rise of Creationism and presents an analysis of how the movement challenges scientific certainty. Osborn, Henry Fairfield. Evolution and Religion in Education. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons 1926. *In response largely to the Scopes Trial, this compendium of essays on evolution presents both the case for a coexistence between religion and evolution in addition to arguments for teaching evolution instead of creationism. Furthermore, he presents key players in the evolution and creationism from the early nineteenth century until the 1920s. Paley, William. Natural Theology: or, Evidences of the existence and attributes of the Deity: Collected From The Appearances of Nature. Charlottesville, Va.: Ibis Pub., 1986. *This presents an early argument for intelligent design by an eighteenth century English theologian. His arguments are revealing enough to be sited by Osborn in Evolution and Religion in Education. Modern Synthesis Dobzhansky, Theodosius. Genetics and the Origin of Species. New York: Columbia University Press, 1951. *As originally published in 1942, Dobzhansky presents evolution on the level of population genetics. This applies genetics to Darwin’s theory, by looking at such topics as mutation, isolating mechanisms, diversity, heredity and patterns of evolution. The 1951 edition includes a synthesis of evolutionary advances since the original was published, revealing that a paradigm shift of sorts has occurred in the field that placed Modern Synthesis as the dominant method of evolutionary analysis. Mayr, Ernst. Systematics and the Origin of Species, From the Point of View of a Zoologist. With a new introduction by the author. New York: Dover Publications, 1964. *Mayr analyzes taxonomy from a systematics (categorizing and theorizing) perspective in an attempt to bridge the comprehension gap between systematicists and experimentalists. In doing so, he combines modern systematics with genetics and ecology, and, to a lesser extent, the other fields of biology. Mayr makes his concern with the specialization of the field apparent in his introduction, in addition to identifying where his work remains useful and what parts of it needed correction. Simpson, George Gaylord. The Major Features of Evolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 1953. *Simpson composed this work almost a decade after his ground breaking Tempo and Mode in Evolution at the behest of his publishers. Indented originally as a revision, in its final form it buildings upon it with expanded coverage of topics and expanded Lavinghouse 14 findings, including fossil plants. Both works bring population genetics to paleontology, to extend evolution back into geologic time. Science Studies Kuhn, Thomas S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 2nd ed., enlarged. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970. *Places the history of science as a succession of conceptual and practical shifts that Kuhn dubs ‘paradigms.’ Much of the methodology included is the basis of sociological work in science into the present; furthermore, the work brought science studies to a wider audience. Merton, Robert K. The Sociology of Science. Norman W. Storer, ed. Chicago: Chicago Press, 1974. *Merton provides a sociological perspective on science that introduces the ethos of science: disinterestedness, universalism, communism, and organized skepticism. Taken as a whole, this is the 20th century ideal of how science should operate. For general overview of the development of science in the west: Lindberg, David C. The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Tradition in Philosophical, Religious and Institutional Context, 600BC to AD 1450. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992. Oster, Malcolm, Science in Europe 1500-1800: A Primary Source Reader. New York Palgrave, 2002 and the companion volume, Science in Europe, 1500-1800: A Secondary Source Reader.