Tennyson's Ulysses: Analysis of a Dramatic Monologue

advertisement

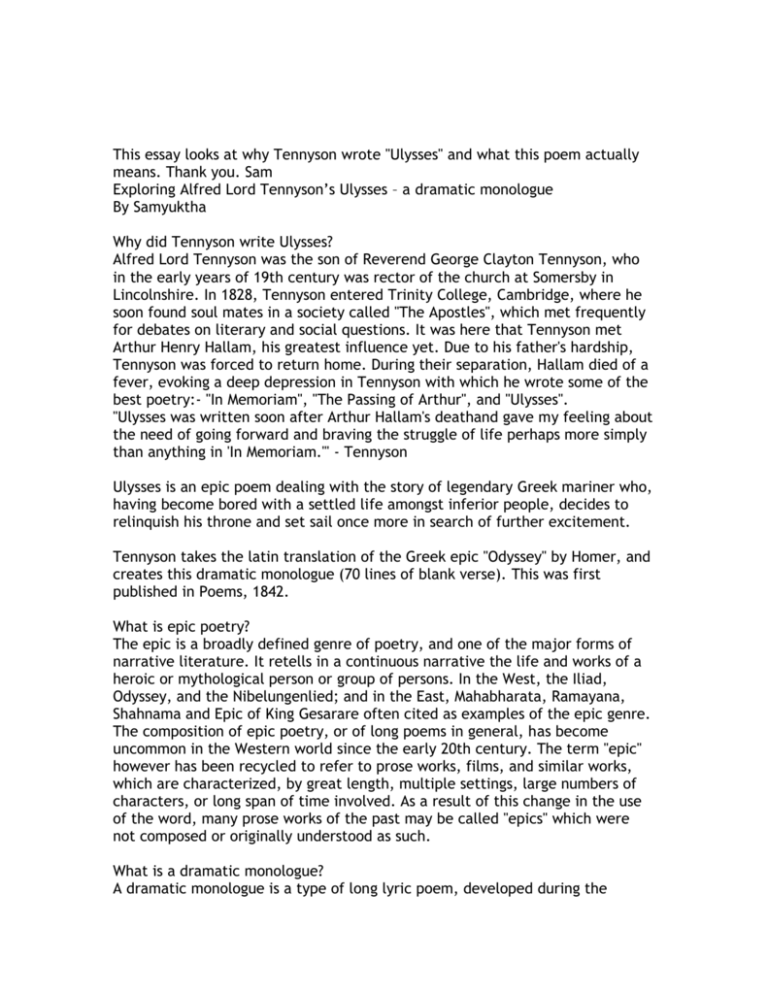

Exploring: Alfred Lord Tennyson's Ulysses - a dramatic monologue This essay looks at why Tennyson wrote "Ulysses" and what this poem actually means. Thank you. Sam Exploring Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Ulysses – a dramatic monologue By Samyuktha Why did Tennyson write Ulysses? Alfred Lord Tennyson was the son of Reverend George Clayton Tennyson, who in the early years of 19th century was rector of the church at Somersby in Lincolnshire. In 1828, Tennyson entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he soon found soul mates in a society called "The Apostles", which met frequently for debates on literary and social questions. It was here that Tennyson met Arthur Henry Hallam, his greatest influence yet. Due to his father's hardship, Tennyson was forced to return home. During their separation, Hallam died of a fever, evoking a deep depression in Tennyson with which he wrote some of the best poetry:- "In Memoriam", "The Passing of Arthur", and "Ulysses". "Ulysses was written soon after Arthur Hallam's deathand gave my feeling about the need of going forward and braving the struggle of life perhaps more simply than anything in 'In Memoriam.'" - Tennyson Ulysses is an epic poem dealing with the story of legendary Greek mariner who, having become bored with a settled life amongst inferior people, decides to relinquish his throne and set sail once more in search of further excitement. Tennyson takes the latin translation of the Greek epic "Odyssey" by Homer, and creates this dramatic monologue (70 lines of blank verse). This was first published in Poems, 1842. What is epic poetry? The epic is a broadly defined genre of poetry, and one of the major forms of narrative literature. It retells in a continuous narrative the life and works of a heroic or mythological person or group of persons. In the West, the Iliad, Odyssey, and the Nibelungenlied; and in the East, Mahabharata, Ramayana, Shahnama and Epic of King Gesarare often cited as examples of the epic genre. The composition of epic poetry, or of long poems in general, has become uncommon in the Western world since the early 20th century. The term "epic" however has been recycled to refer to prose works, films, and similar works, which are characterized, by great length, multiple settings, large numbers of characters, or long span of time involved. As a result of this change in the use of the word, many prose works of the past may be called "epics" which were not composed or originally understood as such. What is a dramatic monologue? A dramatic monologue is a type of long lyric poem, developed during the Victorian period, in which a character in fiction or in history delivers a lengthy speech explaining his or her feelings, actions, or motives. The monologue is usually directed toward a silent audience, with the speaker's words influenced by a critical situation. UNDERSTANDING THE POEM This poem can be understood in three parts: Lines 1 to 23: Verse 1: explores the reasons for his boredom referring to his earlier adventures with his courageous mariners Lines 24 to 43: Verse 2: explores his desire to travel more and plans to place Telemachus on the throne Lines 44 to 70: Verse 3: Ulysses overlooks the harbour and explains where he intends to sail talking about his indifference to death and age... EXPLANATION 1. It little profits that an idle king, 2. By this still hearth, among these barren crags, Ulysses refers to the sterility of life about him. He is the king, but everything is frozen: the fireplace cold, the cliffs harsh and lifeless, even his wife has lost her sensual appetite and is quite useless to him. 3. Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole 4. Unequal laws unto a savage race, 5. That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me. Ulysses has the immense experience of many adventures. He is obviously a philosopher and an intelligent person. The people, over whom he rules, on the other hand, are uncouth and boorish. A very difficult situation for a ruler, where his wise laws are all beyond the understanding of his people. 6. I cannot rest from travel: I will drink 7. Life to the lees: all times I have enjoy'd the lees is the sediment found at the bottom of a bottle of wine. In the old days where there was no adequate means to filter the wine before bottling it, an amount of gunk always found its way into the bottle and would settle at the bottom. One had to be careful, in pouring the wine, not to disturb it. To drink right down to the lees, therefore, meant to drink everything, right down to the bottom of the bottle. 8. Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those 9. That loved me, and alone; on shore, and when 10. Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades 11. Vext the dim sea: I am become a name; The Hyades is a constellation of stars which looks very dim and misty in the night sky and which was therefore associated with rain . If you've ever been at sea, or been at a coastal town (like Cape Town in the winter) and watched the rain sweep across the ocean, you will have noticed how it "scuds" across the water and dims or obliterates (vexes or troubles) the horizon. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. For always roaming with a hungry heart Much have I seen and known; cities of men And manners, climates, councils, governments, Myself not least, but honour'd of them all; And drunk delight of battle with my peers; Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy. I am part of all that I have met; Yet all experience is an arch wherethro' Gleams that untravell'd world, whose margin fades For ever and for ever when I move. The poet is using the tried and trusted image of life being a river, flowing ever onward but, in this case, there is a series of arches over the river through which the traveler must pass. But once one is through one arch, another arch appears, and on and on to the end of life. Beyond the arch, of course, is the future. 22. How dull it is to pause, to make an end, 23. To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use! It compares life to ancient weapons, like swords and chain mail, which rusted if not constantly looked after, not used. The active soldier would spend much time polishing and sharpening the blade to keep the rust at bay. 24. 25. 26. 27. As tho' to breath were life. Life piled on life Were all to little, and of one to me Little remains: but every hour is saved From that eternal silence, something more, the "eternal silence" is, of course, a euphemism for death. Ulysses is getting old but he realizes that dedication to a life of adventure will push back the moment of death. His old age and fear of dying, but rejects death’s attempt to muscle its way into his life. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. A bringer of new things; and vile it were For some three suns to store and hoard myself, And this gray spirit yearning in desire To follow knowledge like a sinking star, Beyond the utmost bound of human thought. The word spirit denotes a being that is full of life. Indeed, the human spirit is the life force within the body. In this case it is a gray spirit because the speaker is getting on in years and his hair is going silver-grey. At the same time, the concept of a grey head denotes wisdom. The wisdom of the speaker is then reinforced by his determination to seek knowledge. He uses the tried and tested image of the star, which was used to guide ships at night. So trustworthy was this, that ships could sail around the world in their quests for fortune, guided at all times by the stars. The old man, still full of enthusiasm, seeks knowledge — just like the sailing ship seeks the stars to chart its progress. So great is Ulysses zest for knowledge that it is beyond the bounds of human thought. No human can think this expansively! 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. This is my son, mine own Telemachus, To whom I leave the sceptre and the isleWell-loved of me, discerning to fulfil This labour, by slow prudence to make mild A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees what the people of Ithaca needed was a ruler who had plenty of patience to civilize them. Ulysses believed that he himself was incapable of such patience but he had faith that his son, Telemachus, was admirably equipped for the work. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. Subdue them to the useful and the good. Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere Of common duties, decent not to fail In offices of tenderness, and pay Meet adoration to my household gods, the ancient peoples had many gods. There were gods everywhere - gods in the mountains, gods in the plains, gods in the cities, river gods, fruit gods and gods of the harvest. In short, there were gods for every occasion. Each city and town had its own gods, and each household too had its own. The Greeks believed that these gods were fairly malicious beings who might take revenge if not appeased with ample offerings. It was therefore dangerous for Ulysses to set sail while leaving his own household gods unappeased. They might, for example, decide to sink his ship! It was therefore a relief for him that he could trust Telemachus to make offerings to his gods for him. His journey might then be a safe one. 43. 44. 45. 46. When I am gone. He works his work, I mine. There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail: There gloom the dark broad seas. My mariners, Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me- = mariners, who have been with him through the bad times unlike his wife who was unable to. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. That ever with a frolic welcome took The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed Free hearts, free foreheads- you and I are old; Old age had yet his honour and his toil; Death closes all: but something ere the end, Some work of noble note, may yet be done, Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods. The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks: The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep Moans round with many voices. The poet appears to be using a combination of onomatopoeia and personification. He compares the sea to a person who is moaning from a deep and everlasting sadness. At the same time, the word “moaning" captures the sound made by the waves. The "many voices” applies to the many waves, lapping and moaning in different tones. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. Come, my friends, 'Tis not too late to seek a newer world. Push off, and sitting well in order smite The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths Of all the western stars, until I die. The Mediterranean Sea was the centre of the universe for the Greeks. Yet they knew that, if they sailed ever westward towards the setting sun, they would pass through the Straits of Gibraltar and out into the Atlantic Ocean. It is clear that this voyage had taken place at least once, because the Greeks knew of the existence of a series of islands off the coast of Africa. They called these islands the Happy Isles where lived the spirits of the dead. So, says Ulysses, if they sailed towards the sunset and out into the ocean where the stars were washed each night, it was possible to meet Achilles once more. (Achilles had fought with Ulysses at Troy where he had been killed, and presumably now lived at the Happy Isles.) 62. It may be that the gulfs will wash us down: 63. It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles, 64. And see the great Achilles, whom we knew. Come my friends let's away now and row this ship into the deep waters of the Mediterranean, then head westward to where the sunsets, and keep sailing till we die. Who knows what lands we may reach? Perhaps even Heaven itself where we might be honoured to make the acquaintance of the great Achilles once more. We are what we are, but we still have a morsel of life left in us to achieve amazing things 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho' We are not now that strength which in the old days Moved earth and heaven; that which we are, we are; One equal-temper of heroic hearts, Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield. Tennyson seals the bond and gives us a connection to Ulysses’ courageous mission. We are left with the encouraging Idea that no matter how old we might be physically the soul lives on. [1842] PARAPHRASE It is of little use for a king to remain idle, bored out of his bracket, and ruling a people who simply are unable to appreciate me. Indeed, many don't even know me! I can no longer rest from the excitement of traveling. I intend to live life to the full. I have enjoyed my life immensely thus far, even though there has often been hardship, both on shore and upon the stormy seas. I am a legend for what I have seen and done, for the strange peoples, lands and governments I have visited. I have been everyone's equal, and have delighted in fighting alongside my fellow soldiers, even far away from home on the battlefields of Troy. Adventure runs in my blood, but my life is now pathetically boring. And yet, despite my advancing age, I still feel I can hold death at bay for just a little bit more by undertaking further exciting adventures and fulfilling my passionate thirst for knowledge. I shall therefore abdicate my throne in favour of my son, Telemachus. He's a trustworthy fellow who will rule wisely, slowly civilizing these boorish people so as to make them industrious and useful. He knows what he must do, and I can rely on him. He will also make sure to keep my household gods satisfied so that they won't get angry in my absence and sink my ship while I'm not looking. There below me is the harbour. The ship has all her sails ready for departure. My sailors are trustworthy folk who have delighted in sharing my previous adventures, who love fun and excitement, and who are also capable of tough work and hardship. It's true we are all old, but we are still capable of a bit more from life. After all, death brings an end to everything, so we must live it up now while we still have the chance. The night is approaching, the moon is rising slowly into the sky, and the lights of the harbour are beginning to twinkle. UNDERSTANDING THE CHARACTER Ulysses is a heroic ancient mariner who is looking at his life afresh and feels he misses the essence of it - adventure. He does not see himself as a king who will rule until death over some people who just blindly follow him. He does not want the responsibilities of a king, husband or father. Instead, he was traveling abroad consoling with kings, generals and gods, traveling to “cities of men / and manners, climates, councils, governments”(13-14). Through his monologue he contrasts himself with his son. Ulysses - the life of infinite search Telemachus - the life conscientious absorption in duty Ulysses condescends his own son by describing his timid self to rule the people and how his son is more capable of the common duties. All he knows is to travel and that is all he sees himself yearning to do. http://oldpoetry.com/column/show/32