Running head: TEEN DEPRESSION & SUICIDE

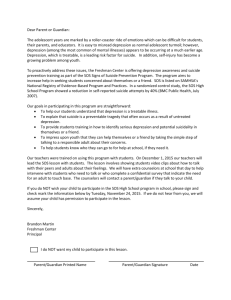

advertisement

Teen Depression & Suicide Running head: TEEN DEPRESSION & SUICIDE Teen Depression & Suicide in the United States Katheryn Moran Western Washington University 1 Teen Depression & Suicide Table of Contents Introduction & Research Statement 3 Literature Review 3-7 Research Methods 7-9 Results & Discussion 9-11 References Cited 12-13 Appendix 14 Abstract 15 2 Teen Depression & Suicide 3 Introduction & Research Statement There are a variety of issues that teens in America face on a daily basis alongside the growing pains that every developing adolescent experiences. Depression and suicide amongst teens in America are serious issues that are prominent in my mind and deserve a closer examination of the possible links between the two. There have been studies done to find reasons for depression and suicide in teens, whether or not these reasons link to parents or child rearing and the kinds of environments that are more likely to cultivate depression or suicidal thoughts amongst adolescents. I would like to research all of these topics and ask the overarching question: What are the triggers and links in a teenager’s life to bring on depression and/or suicidal thoughts and are there any ways to prevent them? Literature Review Depression is categorized as the most common psychiatric disorder in the United States and has become increasingly recognized to begin in adolescence (Facts for Families, 2008). It is a disorder that affects emotions, thoughts, sense of self, behaviors, interpersonal relations, physical functioning, biological processes, work productivity and overall quality of life (Hankin, 2006, p.102). There are varying degrees of depression ranging from mild to severe clinical depression. It is important to recognize that individuals of all ages can be victims of depression. Categorizing by degree of severity ignores criteria that are developmentally sensitive over the life span. For example, preschoolers are less likely to report depressive symptoms than adolescents who are obviously more educated, developmentally and socially mature Teen Depression & Suicide 4 (Hankin, 2006, p. 103). However, we should not assume that different ages experience depression any more or any less. Rather, their emotions may correspond directly to their age, knowledge and experience and cause different reactions (Hankin, 2006, p. 104). There are a variety of triggers for depression in any individual. Hankin (2006) claims that the most promising approach to understanding causes of depression in youth is through a vulnerability-stress framework. Almost all individuals with a depressive disorder have experienced at least one negative event in their life before the onset of depression. In a three-wave, one year longitudinal study Hankin (2006) found a dramatic increase in the number of uncontrollable negative life events experienced starting at age thirteen (p. 105). The most typical stressors that contribute to the onset of depression include social outcasting, parental divorce, a drastic change in environment, self-doubt, financial uncertainty and pressure to succeed and fit in (Facts for Families, 2008). Stress, however, is not the only link to depression. Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, & Lyubchik (2000) believe that parental depression is related to a wide range of impaired developmental outcomes in children and can be a leading factor in the onset of depression. Their research shows that “children of depressed mothers show greater social, behavioral and academic impairment than children of non-depressed mothers, from infancy to adolescence” (p. 148). Due to the negative interactions and relationships this child is exposed to, it makes sense that they would be more prone to the development of similar personality traits and characteristics. “Children of depressed mothers are more likely to have psychological symptoms, treatment for emotional Teen Depression & Suicide 5 problems, suicidal behavior and psychiatric diagnoses” (Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, & Lyubchik, 2000, p. 148). Other life obstacles and hindrances that teens typically face include substance abuse; mental illness; impulsive, aggressive, and antisocial behavior; a variety of family factors; and increased access to firearms by the at-risk population (Centers for Disease Control, 1995). All of these have been documented as direct causes of increased odds of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts population (Centers for Disease Control, 1995). Depending on the population type, some individuals are more susceptible to increased depression and suicidal thoughts simply due to their environment and history. Those teens that do indulge in the use of substances are at a much higher risk than those who abstain (Hallfors, Waller, Ford, Halpern, Brodish, & Iritani,, 2004, p. 224). Depending on the age, statistics show that some girls are more likely to attempt suicide than boys (Gore, 2008). Whether we are predisposed to it, if it is caused by stress or we were exposed to it from birth, depression is all around us. Unfortunately, depression is the number one cause of suicide among teenagers in the U.S. (Facts for Families, 2008). Suicide among teenagers in America has crept up to the third leading cause of death among individuals between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four. Each year thousands of teenagers resort to suicide (“Facts for Families”, 2008). It is important to understand why all of the previously mentioned triggers so significantly impact the life of a teenager. By understanding this and recognizing symptoms of depression early on, perhaps we can begin to decrease the number of people affected by depression and haunted by suicide. Beginning the installation of a variety of different kinds of educational and Teen Depression & Suicide 6 preventative programs around the country has already positively effected many people’s lives in America. McArt., Shulman, & Gajary (1999) proposed the idea of a community intervention system in New York to begin mending the relationship between community and teen. They did so by creating an open workshop space for teens to discuss and share themselves and their experiences. They also offered classes to educate teens about the resources at their disposal in their own community. This program focused extensively on “help-seeking strategies” when faced with an emotional crisis and improving access to mental health crisis services. (McArt., Shulman, & Gajary , 1999, p. 3). This program allowed for group healing and a social process that brought people together to create a support system and also taught self help and empowerment behaviors. “Many adolescents do not obtain services they need because the services are not known to them or to their families, and are not perceived to be readily accessible” (McArt., Shulman, & Gajary , 1999, p. 2). By raising awareness about depression in this New York community, more teens felt they had a support system to turn to that had not existed before. Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, & Lyubchik believe that this gap in services could be addressed by developing family-support teams as collaborative services between psychiatry and pediatric services beginning at the birth of the child (2000, p. 152). Recognizing that the early environment of a child has a serious impact on their development, providing services from the beginning may halt any early depression symptoms and provide the family with the tools necessary to seek help if needed later on. By combining the expertise of a family psychiatrist and pediatrician, a wrap around Teen Depression & Suicide 7 service can be implemented for the family and hopefully build a support web of current developmental knowledge and clinical skill in working with parents and infants (LyonsRuth, Wolfe, & Lyubchik, 2000, p. 152). Raising awareness of depression and creating supports for families and individuals to seek out in their own communities have proven to be one of the most effective tools in exposing the reality of the situation and beginning the healing process (Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, & Lyubchik, 2000, p. 148). Research Methods I have chosen to focus on the impact of the family and environment on youth development. I plan to conduct my research using a probability sampling method, much like the Commonwealth Study mentioned by Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe & Lyubchik (2000). I also plan to limit my research to the city of Bellingham. By using the cluster sampling method I can find each household in Bellingham that houses teenagers between the ages of 13-18. According to current Bellingham demographics, there are approximately 6,000 teenagers in the city (AreaConnect, 2000). Once I have found these houses I can use a simple random sampling method to decide which households I will send questionnaires to. I am aiming for a representative sample of about half of the population, so I plan to send around 3,500 questionnaires. Questionnaires will be sent not only to the teenager(s) within the home, but also to the parent(s). I am interested in finding out the current social, emotional and cognitive status of the adolescent(s) and parent(s) and what experiences or situations may be affecting that youth’s current lifestyle. The following is a sample of the questions I will be sending to my participants: Teen Depression & Suicide 8 Sent to teens: Do you feel depressed? Do you feel satisfied? Have you ever experienced suicidal thoughts or feelings? Are you often physically active in your current lifestyle? Do you enjoy social outings? Do you feel comfortable at home? Do you feel that you can approach your family or close friends with problems you face? Sent to parents: Do you feel depressed? Do you feel satisfied? Have you ever experienced any type of depression? Are you often physically active in your current lifestyle? Do you enjoy social outings? Do you ever worry that you child may be facing depression? Do you sense any links between your child’s behavior and the way you raised them? Each question will be followed by the numbers one through four and directions will ask the participant to circle the number that best corresponds to their answer. The number one will correspond to the answer never, four corresponding to always. I plan to leave a section at the bottom of the survey encouraging participants to include any extra information that they desire, but I am aware that this may not accumulate much response. Although I plan to survey the adolescent and parent separately, I recognize the importance of obtaining permission for gathering information from minors and the sensitivity of this subject. So, I plan to mail both questionnaires in one envelope. The contents will be headed with a description of the research and a permission slip for the parent or legal guardian of the participant to sign and return with the survey. This will be followed by reassurance of the confidentiality of this information and it’s use strictly as a way of improving services for depression in Bellingham as a whole. I also plan to Teen Depression & Suicide 9 include information regarding supports and counseling systems that are available to participants if needed after the involvement in this research. I feel that the results of this survey will be reliable because these questions are straightforward and relatively easy to answer. By using the vocabulary always and never to describe the occurrence of feelings and situations, the choice is made clear and obvious to the participant. I feel that the questions I am asking are blunt and require honest answers. I feel that these answers will confirm existing links between adolescent behaviors and lifestyles and their family members or disprove these beliefs. I plan to take all collected data and find the average outcome for each answer for teenager and parent. By randomly selecting my participants I am able to assume that my sample is representative of the majority of adolescents and families with teens in the Bellingham area and apply my results to a larger population. Results & Discussion I received 2,000 surveys back after mailing 3,500. Each survey returned included data for both parents and teens along with the consent forms needed. The results were somewhat surprising in that I had expected a strong link between parental depression and adolescent depression. Instead, I found depression to be more prominent in adults alongside lack of satisfaction. However, It did seem that adolescents found themselves to be less depressed and more satisfied in direct correlation to how active and social their current lifestyle was. It seemed that a majority of teens felt comfortable at home and had a feeling of support from friends and family. Those parents that did report Teen Depression & Suicide 10 feeling worried about their children also reported seeing significant links between their child rearing practices and their child’s behavior. Will this data does not necessarily support the link between parental depression and it’s link to possible causation or influence on teen depression, it does show the importance of recognizing depression as an issue many people face. With this data I see depression as a problem that is significant in the Bellingham population and should be addressed immediately. By installing forms of previously discussed preventative and educational programs, I think many teenagers and adults would feel more comfortable discussing their experiences with depression and beginning to sort through those emotions to find the root problem. I think these programs can lead to a happier, healthier community and encourage community bonding and understanding. Adolescent Survey Results Depressed? Satisfied? Suicidal Thoughts? Physically Active? Social? Comfortable at Home? Support System? 1=Never 2=Sometimes 3=Usually 4=Always 100 900 700 300 800 700 300 900 550 250 500 400 350 1150 250 400 300 1000 350 350 1000 300 200 350 350 250 300 300 Parental Survey Results Depressed? Satisfied? Suicidal Thoughts? Physically Active? Social? Worry About Kids? Child Rearing Links? 1=Never 2=Sometimes 3=Usually 4=Always 600 600 300 400 600 600 300 900 700 700 400 600 400 800 300 200 900 500 300 700 600 500 400 100 300 500 400 400 Teen Depression & Suicide 11 1400 1200 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1=Never . rt. . Su pp o Co m fo r t. .. l? So cia ca l.. Ph ys i ... Su ici da l fie Sa tis De pr es . d? 2=Sometimes .. Number of Teens Adolescent Survery Results 3=Usually 4=Always Questions Asked 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1=Never Questions Asked e. .. R ld Ch i W or ry ... l? So cia ca ... Ph ys i Su ici da l ... d? fie Sa tis .. 2=Sometimes De pr es . Number of Parents Parental Survey Results 3=Usually 4=Always Teen Depression & Suicide 12 References American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2008). Facts for families: Teen suicide. (2008, May). Retrieved July 6, 2009, from http://www.aacap.org/cs/root/facts_for_families/teen_suicide AreaConnect (2000). Bellingham city, Washington statistics and demographics. Retrieved August 8, 2009, from http://bellingham.areaconnect.com/statistics.htm Centers for Disease Control. (1995). Suicide among children, adolescents, and young adults. United States, 1980-1992. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 44, 289291. Chess, S., & Hertzig, M. E. (1989). Annual progress in child psychiatry and child development 1989: A selection of the year's outstanding contributions to the understanding and treatment of the normal and disturbed child. New York: Brunner Mazel. Dube, R. S., Anda, R. F., Felitti, J. V., Chapman, D. P., Williamson, D. F., & Giles, W. H. (2001). Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the adverse childhood experience study. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 286, 3089-3096. Retrieved July 5, 2009, from the ProQuest database. Gore, K. A. (2008). Social integration and gender differences in adolescent depression: School context, friendship groups, and romantic relations. Retrieved July 3, 2009, from the ProQuest database. Teen Depression & Suicide 13 Hallfors, D. D., Waller, M. W., Ford, C. A., Halpern, C. T., Brodish, P. H., & Iritani, B. (2004). Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of of Preventive Medicine, 27, 224-231. Retrieved July 5, 2009, from the ProQuest database. Hankin, B. L. (2006). Adolescent depression: Description, causes and interventions. Epilepsy & Behavior, 8(1 ), 102-114. Retrieved July 5, 2009, from the ProQuest database. Lyons-Ruth, K., Wolfe, R., Lyubchik, A. (2000). Depression and the parenting of young children: Making the case for early preventative mental health services. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 8(3), 148-153. McArt, E. W., Shulman, D. A., & Gajary, E. (1999). Developing an educational workshop on teen depression and suicide: A proactive community intervention. Child Welfare Journal, 78(6), 793-806. Retrieved July 5, 2009, from the EBSCO database. Reifman, A., & Windle, M. (1995). Adolescent suicidal behaviors as a function of depression, hopelessness, alcohol use, and social support: A longitudinal investigation. American Journal of Community Psychology: Behavioral Science, 23(3), 329-354. Solomon, C. (2009). Parent’s depression and its relation to adolescent suicide attempts. Undergraduate Research Journal for the Human Sciences. Retrieved July 6, 2009, from http://www.kon.org/urc/v8/solomon.html Teen Depression & Suicide 14 Teen Depression & Suicide 15 Abstract Depression and suicide amongst teens in America are serious issues that are prominent and deserve a closer examination of the possible causes. There have been studies done to find reasons for depression and suicide in teens, whether or not these reasons link to parents or child rearing and the kinds of environments that are more likely to cultivate depression or suicidal thoughts amongst adolescents. I ask the question: What are the triggers and links in a teenager’s life to bring on depression and/or suicidal thoughts and are there any ways to prevent them? Though there are a variety of situations and experiences that can cultivate depression, stress, environment and sociability have the most significant impacts. Research done by Hankin (2006) suggests that the only way for us to truly understand a teen’s depression is through a vulnerability-stress framework. Lyons-Ruth, Wolfe, & Lyubchik (2000) argue that parental depression and early environment play the most critical role in the development of depression. In my own research I could very clearly see the impacts of depression on lifestyle and satisfaction with one’s own life that brought me to conclude that preventative and educational systems need to be put in place throughout America to begin the breakdown of depression and commonality of suicide. A few different successful approaches to preventative and educational systems are discussed in this paper alongside facts and results from other similar studies that suggest something be done, and soon.