Final Exam

advertisement

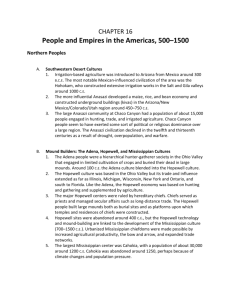

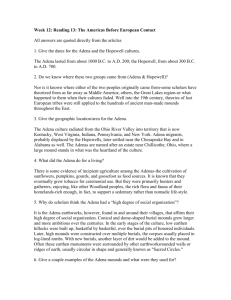

Andrea M. Ranada April 23, 2003 Final Exam 1A Poverty Point, located in present-day Louisiana, existed between 2200 B.C. and 700 B.C. This area has six concentric Great Earthworks as well as six rivers that converge. The site lies on the Macon Ridge over the Mississippi floodplain near the confluent rivers. The inhabitants participated in intensive labor within kinship groups. Interestingly, there are no burials or tombs at Poverty Point, perhaps bearing a symbolic value to the people of the region. However, this area features mounds, such as West Mound. This mound presents the archaeoastronomical features of Poverty Point, particularly because during the spring and fall equinoxes the sun rises to the east and falls directly across the center of earthworks. Material remains found at Poverty Point include animal engravings and ornaments which suggest that the inhabitants were animistic or believed that spiritual beings animated nature. The exchange system at Poverty Point includes copper, galena, jasper, quartz, and soapstone. Apparently, each site specialized in the production of specific items such as hoes, plummets, and ornaments according to which resources were locally available. The population of Poverty Point relied on fishing as a form of subsistence. They also consumed reptiles, large mammals, birds, clams, and oysters as well as acorn and hickory nuts. They used earth ovens to prepare their food. This usually consists of clay balls (which were actually made of silt) that are heated up to warm the ovens. 1 1B The Adena is essentially a burial complex that existed from 3500 B.P. to 2600 B.P. The Adena region generally encompasses present-day Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. The Adena culture subsisted on domesticated seed crops and also hunted elk, bear, deer, beaver, and turkey. Additionally, the Adena settlement has round structures accompanied by thatched roofs. An Adena structure specifically has internal hearths with burials underneath the settlement. In terms of artifacts, the Adena made pottery with rounds bottoms and also possessed chert hoes, arrow points, and neck ornaments called gorgets. These objects were sometimes part of a reciprocal exchange that the Adena practiced, in which exchanges were made face-to-face in order to promote and maintain outside social relationships. As mentioned earlier, the Adena is mostly a burial complex. Most of the sites are burial mounds such as Robbins Mound in Kentucky. In burials, most of the bodies were cremated. Some of the bodies were associated with ochre, graphite, gorgets, and engraved stone tablets adorned with animal motifs. The Adena burials indicate a mostly egalitarian society, but some of the Adena “elite” were buried with their bones covered with red ochre and graphite. Around 2000 B.P., a drastic cultural change occurred along with the creation of large burial chambers. These chambers were once structures that were built and burned. Mounds were then built where these structures once were. Elaborate grave goods were also found in these structures, including shells, copper, mica, and zoomorphic stone pipes. Some burials also contained polished “trophy skulls.” 2 1C The Mississippian culture existed from 900 A.D. to 1500 A.D. Its social organization is primarily a chiefdom with low and high level chiefs. The Mississippian population heavily relied on maize farming, beans, squash, and sunflower. They also adapted to the floodplains that consisted of wild vegetables, fish, game, and waterfowl. Essentially, the floodplains served to consistently refertilize the soil with new nutrients. Most of these resources, especially grain, were redistributed. Redistribution is a form of exchange in which goods flow into a central place and then sorted, counted, and reallocated. This provided for conspicuous consumption, allowing the display of wealth for social prestige. Redistribution also allowed for the conversion of subsistence surplus into wealth during times of abundance and its conversion back into subsistence items during times of need. Feasts facilitated redistribution of goods and were also conducted to reaffirm ties of villages and to consolidate authority. Local production and trade only involved ceramics and basketry, but copper, shell, chert hoes, and mica were obtained extensively from the Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, Illinois, and the Appalachians respectively. Mississippian elite was buried with axes, maces, exotic items and other weapons that apparently solidified alliances. The Mississippians also believed that renewal rebuilding of the mounds perpetuated fertility and that having a Green Corn ceremony would ensure a successful harvest. The Hopewell culture, which precedes the Mississippian culture, has settlements that consist mostly of single-family homesteads. Some of the villages are also associated with burial mounds and may represent the location of chiefs. Typically, the settlements have large house floor areas with bark-covered rectangular mats, storage pits, hearths, and pottery that appear to be squat vessels with thickened rims and animal designs. 3 The mortuary customs of the Hopewell culture is very complex. There are about 1,150 burials found in Ohio that are related to the Hopewell culture. One particular site in Serpent Mound, Ohio has effigy mounds that display geometric patterns and animal motifs. With an average height of 30 feet and a length of 100 feet, 200,000 hours is the estimated time it took to build these mounds. Each mound contains Charnel houses (where the body decays) of a particular lineage or clan. Once the houses became full of dead bodies, they were burned. As with the Mississippian culture, the Hopewell elite was buried intact, particularly in log-lined tombs within the charnel houses. These burials had exotic grave goods such a copper, bone, mica, shell, obsidian jewelry, axes, masks, and fabrics. If an individual was buried with only one type (such as mica), then that individual might have been a specialist of that type. The burials also had zoomorphic designs with clan totems and symbols. The Hopewell exchange systems were similar to the Mississippian. Mississippian redistribution involved elite storage and the redistribution of grain. Similarly, Hopewell redistribution was a central institution that controlled the movement of goods. Some of the goods were copper and silver (which made axes, breastplates, headdresses, and ritual objects) or mica (which made geometric figures and motifs). Beads composed of marine shells, projectile points composed of obsidian, and quartz crystals were also among the redistributed goods. Consequently, the Hopewell and Mississippian cultures are fairly similar in their settlements, mortuary customs, social status, and exchange systems. However, the Mississippian culture has distinctive social and religious customs that the sets it apart from the Hopewell culture. 4 1D James Knight theorizes three cults that emphasizes either warfare, earth / fertility, or ancestor worship. The first cult, which was supposedly composed of elite nobles focused on warfare, is also known as the “Southern Cult.” This cult can be identified by exotic motifs and symbols and by the presence of expensive raw materials such as seashell or imported copper. These often appear in elite burials that also feature war axes, maces, and other types of weapons. Warfare symbolism also includes exotic cosmic imagery as well as images of animals, humans, and mythic beasts. This cult is very exclusive, only allowing certain kin groups to participate and giving privileged rights to chiefly posts within these groups. The second of the Mississippian cults focuses on the earth and fertility. This cult is associated with the earthen platform mounds. Interestingly, rebuilding these mounds by adding additional layers of earth over the burials symbolizes renewal. The platform mound symbolizes the earth, so ultimately as a whole it represents the renewal of earth. Unlike the first cult, the platform mound cults were involved in communal rituals that allowed the participation of entire kin groups and communities. These people were all involved in constructing the platform mounds as part of a religious ceremony. The third Mississippian cult concentrates on ancestor worship. Priests who were responsible for maintaining temples, burial houses, sacred fires, and mortuary rituals supervised these cults. Knight suggests that individuals with special supernatural powers supervised the ancestor rituals. Given that the warfare cult is a chiefly cult and that the platform mound cult was a communal cult, the ancestor cults served a mediator between the two cults and hence the different interests within the Mississippian society. 5