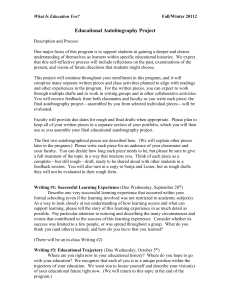

Write a brief account of what draws you to this

advertisement

Kate Feldmann Working with Manuscripts Karen Sanchez-Eppler 10/20/11 Identification (Second Draft) I was delighted to find a wealth of manuscripts at the Sophia Smith Collection that consist of children’s stories. These exciting discoveries exist within the boxes of Ethel Parton Writings—a series within the Fanny Fern and Ethel Parton Papers. Ethel began to write for children in her seventies (it will be interesting to investigate why she started so late), and covered a wide range of topics, including a witty piece on “How the Dahlia Entered Good Society” and short about “Great Folk As Little Folk”. The stories are usually very short, typically two-pages in length, and are almost always accompanied by their early drafts. I was drawn to these documents because of my love for children’s literature, and my ambition to become a children’s book editor. I find that originality in children’s stories comes from the voice, rather than the subject matter, and there is so much that attracts me to that refreshing departure from adult works. Ethel Parton’s papers encapsulate much of what excites me about children’s literature—there is fun and life to them. There is wit and creativity. The stories are quirky and over quickly (a benefit for those that are not as interesting as others). As for the manuscripts in their flesh, I noticed in revising this paper that I initially included much more biography than was called for because there is so little to describe about the physical papers. It is my one regret about choosing to work mainly with typeddrafts—that the physical copy of the manuscript does not offer as much visual life and personality as a scrapbook or a diary or hand-made books might. Though Ethel herself labored over these works, typing each draft, there is an element of distance in typewritten work—perhaps because type does not have as much personality as script. The established guidelines for typed work (margins, spacing, punctuation, spelling)—elements that the writer is not as adamant to follow or correct in personal notes and hand-written drafts— are also limiting of personality, and restrain the reader’s ability to interpret the thought process of the writer beyond their story itself offers. There is of course Ethel’s handwriting, scratched over typed-edit drafts and sprawled across notepad paper and filling lined paper with stories, but most of what I will be working with exists within the text and in the surrounding history and context. Nevertheless it is a thrill to work with children’s manuscripts from the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century—one of my favorite times in children’s book history—when Peter and Wendy and Winnie-the-Pooh were just being introduced! The physical papers occupy several folders. Because Ethel Parton writes very short stories, I would like to work with many of her manuscripts, and these manuscripts range in material form. The papers that I perused most where those that eventually became “Great Folk as Little Folk”. The first of these papers was mis-filed under “Flower, Fruit and Fancy”—where the idea for the work was indicated on brittle yellow pieces of paper, clearly from a notepad (some of the papers were still attached at the top by a thin coating of glue). This pad seemed to serve as a place to jot down ideas and notes, for it is about half-way through the papers that we see at the top: “Historic Children—” followed by a list of famous names… 1. Napolean 2. Queen Elizabeth …4. Edward VI 5. Son of Queen Anne 6. Mary Queen of Scots …the list goes on to include 63 names, among them Louis XIII, Mozart, John Keats, Dickens, Joan of Arc, and Victor Hugo. The names listed were clearly added over time, as the first dozen or so are written in black ink in the same script, later in the list names are added in blue or purple ink—the same hand, but in various sizes and states of sloppiness and legibility. At the end of the list reads “Great Folk And Little Folk” OR “Great Folk as Little Folk”. It became clear to me upon reading this that Parton’s intentions were to write stories about these famous folk as children. To my great delight, in some of the further files were drafts of a few of the listed names that Parton had indeed captured in two-page snapshots of Great Folk as little ones. I forget the people that she wrote about, but recall that included with the various drafts of these stories were article clippings that mentioned the historical figure in question. The latest editions of these stories were typed on heavy white paper, in-between drafts on a thinner, more translucent white, and earliest drafts were scrawled in pencil on paper of detail that I cannot recall. On every version save the final draft, Parton had crossed out and revised or commented on lines in a black pen. Though I have a wonderful set of drafts to work with—which not only include the first to final draft, but the scribbled notes of conception—I am curious about Ethel’s intentions. What was it about great historical figures in their youth that inspired Ethel? I hope to discover more as to why this topic intrigued her as I look into her history. Thank god for the typed drafts, because one of the biggest problems that I foresee with Ethel Parton’s papers is her lack of legibility. Her handwriting can be made out with lots of patience and heavy sighs, but it is slow, slow going. Nevertheless, there is something charming and romantic about reading first drafts written out. These days children’s book manuscripts are typed documents—and those documents are edited by making changes over the first and second and third draft and this initial document is essentially the only document and is passed back and forth until the original draft is obscured and only available through a really irritating tracking tool. This process is undoubtedly more practical, more timely, and lest costly, but it creates a distance, at least for me, and masks to a certain extent the personal and intimate exchange between writer and editor. There is a very large attraction for me in being able to hold physical copies of drafts, rather than sorting through one online document that keeps track of all the edits. The majority of the manuscripts that I rifled through consisted of typed drafts of stories, but these were often paired with earlier drafts typed on cheaper paper, notes and scrawlings on scrap-bits of paper, and newspaper clippings that were used as research. There was a longer work included about a princess that may have consisted of around 150-200 pages, but I believe that I will work mainly with Ethel Parton’s shorter stories, drawing mainly upon her works that can be traced from conception to final draft. References "Doesticks Visits the Museum." Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Web. 05 Oct. 2011. <http://chnm.gmu.edu/lostmuseum/lm/32/>. "Fanny Fern and Ethel Parton Papers, 1805-1982 : Biographical and Historical Note." Five College Archives & Manuscript Collections. Web. 02 Oct. 2011. <http://asteria.fivecolleges.edu/findaids/sophiasmith/mnsss19_bioghist.html>. The Youth's Companion Project. Web. 05 Oct. 2011. <http://youthscompanion.com/>.