The Ecosystem Approach - Havforskningsinstituttet

advertisement

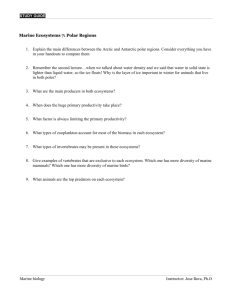

1 Ecosystem based management: definitions and international principles by Ole Arve Misund Institute of Marine Research P.O. Box 1870 N-5817 Bergen, Norway Introduction At IMR, Norway, we have been involved in the development of the ecosystem approach as advisors to political processes like the Fifth International Conference on the Protection of the North Sea held in Bergen in 2002 (NSC 2002), the development of a governmental white paper on integrated marine management in Norway in 2002 (Anon. 2002), the development of the strategic plan of the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) adopted in Copenhagen in 2002 (ICES 2002), and on an institutional level to develop an understanding of the ecosystem approach that led to a reorganisation within the Institute of Marine Research, Norway (Anon. 2001, Misund and Skjoldal 2005). The ecosystem approach has been a central drive for these processes and has been agreed as a management principle in the Bergen Declaration from the 5th North Sea Conference and by the Norwegian Parliament in adopting the governmental white paper. In the following, I will therefore reflect on the experiences from the processes for the North Sea and in Norway on developing the principle of ecosystem approach to management. The Ecosystem Approach Ecosystem approach is a management principle. As such it builds on the recognition that the nature of nature is integrated and that we must take a holistic approach to nature management. The science to support ecosystem approach to management must also be integrated and holistic. A core element of this science is ecology with focus on the properties and dynamics of ecosystems (Fenchel 1987). Many scientists and managers have recognised the need for an 2 ecosystem approach for a long time (Likens 1992), although it is only during the last 10-15 years that a broad awareness of the need for such an approach has developed. The increased awareness and formalisation of the ecosystem approach have emerged as a result of international environmental agreements within the frame of the United Nations, and a fundamental description of the basis of an “ecosystem approach” was first formalised in the Stockholm Declaration in 1972 (Turrell 2004). The most authoritative account of the ecosystem approach is probably that found in Decision V/6 from the meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity in Nairobi, Kenya, in 2000. This decision has an annex with a description, principles and operational guidance for application of the ecosystem approach (www.biodiv.org/decisions/default.asp ). The Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) concept has been the basis for a practical development of ecosystem approach to the management of marine resources and environment (Sherman 1995). Currently, 64 LMEs have been identified dividing mainly the shelf regions of the globe into identified management units. Descriptions and conditions of these LMEs along with a range of general scientific and management issues have been considered in a large number of symposia and published books (www.edc.uri.edu/lme). Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) are geographical entities defined on the basis of ecological criteria. An LME is defined as a relatively large ocean area, typically 200.000 km2 or larger, with characteristic bottom topography, hydrography and productivity, and with trophically coupled populations (that is populations dependent upon each others as prey and predators). Most LMEs are located on the continental shelves. Here the bottom topography has a strong steering of currents and water mass distribution. The physical conditions again determine the characteristics of plankton production. ICES has recently given advice to the EU in connection with the development of a Marine Strategy Directive on the division of the European seas into regions and sub-regions (Fig. 1) (http://www.ices.dk/products/icesadvice/Book1Part1.pdf). ICES reviewed the LME divisions as well as several different biogeographical classification systems. While none of these systems were used directly, the proposed division into ecological regions followed closely the LME divisions, with adjustments of some of the borders. The criteria used to define the ecological regions were also similar to those for identifying LMEs. The regions or sub- 3 regions used in the proposed Marine Strategy Directive are therefore equivalent to Large Marine Ecosystems. In many fisheries science institutions, advisory communities and management bodies, discussions on how to implement and deliver according to the ecosystem approach has been a central issue for the last years. Still, there is no unified and agreed understanding or protocol on how to cope with the challenge of delivering scientific advice for management of fish stocks under the much broader scope of the ecosystem implications of fishing as compared to the traditionally more narrow consideration of the population dynamics of each single fish stock being exploited. The FAO Expert Consultation on Ecosystem-based Fisheries Management in Reykjavik in 2001 (FAO 2003) produced an overall, pragmatic solution for implementing the ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF) by merging ecosystem management and fisheries management, but the practical application of these EAF principles are yet to be implemented in most of the fisheries scientific and advisory bodies around the world. Development of the ecosystem approach for the North Sea The shallow, productive North Sea is an arena for human activities as fishing, dredging, oil and gas exploration, shipping and as recipient for discharges from sources on land or offshore. During the last decades, there has been an increasing awareness of the need for measures to protect the environment of the North Sea. Several International Conference on the Protection of the North Sea have been held, the first in Bremen in Germany in 1987. The Ministers at the 3rd Conference in The Hague in 1990 requested that OSPAR and ICES should establish a North Sea Task Force (NSTF), with one of the tasks being to produce a Quality Status Report (QSR) for the North Sea. This was completed in 1993 (NSTF 1993) and identified fisheries as having major impacts on the North Sea ecosystem. The Ministers at the 5th North Sea Conference in Bergen in 2002, agreed to a framework for the ecosystem approach contained in Annex I to the Bergen Declaration (http://odin.dep.no/md/nsc/declaration/022001-990330/dok-bn.html). This framework has 5 main components that are linked in a decision cycle as shown in a simplified representation in Figure 2. The 5 components are: 4 - objectives, set for the overall condition in the ecosystem and translated into operational objectives or targets; - monitoring and research, to provide updated information on the status and trends and insight into the relationships and mechanisms in the ecosystem; - assessment, building on new information from monitoring and research, of the current situation, including the degree of impacts from human activities; - advice, translating the complexities of nature into a clear and transparent basis for decision-makers and the public; - adaptive management, where measures are tailored to the current situation in order to achieve the agreed objectives. The Ministers at the 3rd Conference in The Hague in 1990 requested that methodology for setting ecological objectives should be developed. This turned out to be a long and rather complicated process with many institutions involved. The NSTF started on the development of the ecological objectives, and OSPAR continued the process. A general approach was adopted by OSPAR in 1997 using the North Sea as a test case. After considerable input of advice from ICES (http://www.ices.dk/products/cooperative.asp), a set of 21 Ecological Quality elements with objectives (EcoQOs) set for 10 of them, were agreed by the Ministers at the 5th North Sea Conference (NSC 2002, Annex 3). Ecological quality is defined as the overall expression of the structure and function of the marine ecosystem. It is expressed by a number of ecological quality elements or variables, reflecting the different parts of the ecosystem, to which objectives or targets (EcoQOs) can be set. Taken together, the suite of EcoQOs can be seen as an envelope defining the acceptable state of the ecosystem compatible with sustainability. This can either be a wide outer envelope of limits which should not be exceeded due to risk of serious or irreversible damage to the ecosystem, or a more restricted inner envelope defined by targets based on some considerations of optimum use of ecosystem goods and services (Fig. 3). The envelope could also be a combination of the two, with outer boundary limits in some parts and optimum target zones in others. A definition of ecosystem approach was proposed by the ICES Study Group on Ecosystem Monitoring and Assessment (ICES 2000): 5 “Integrated management of human activities based on knowledge of ecosystem dynamics to achieve sustainable use of ecosystem goods and services, and maintenance of ecosystem integrity.” This formed the basis for the technical definition of ecosystem approach used in a statement from the First Joint Ministerial Meeting of the Helsinki and OSPAR Commissions (JMM) in Bremen in June 2003 (http://www.ospar.org), and in the work on developing the thematic Marine Strategy within the EU (http://europa.eu.int/comm/environment/water/consult_marine.htm): “The comprehensive integrated management of human activities based on the best available scientific knowledge about the ecosystem and its dynamics, in order to identify and take action on influences which are critical to the health of marine ecosystems, thereby achieving sustainable use of ecosystem goods and services and maintenance of ecosystem integrity.” It is worth stressing the emphasis on integrated management of human activities in this definition. Sector integration is a key element of the ecosystem approach and this has scientific and institutional implications. Scientifically we need the ability to assess the combined impacts from different sectors on the marine ecosystems, and institutionally the sectors need to work closely together. This means for instance that close collaboration between the fisheries and environmental conservation sectors is a prerequisite for an effective ecosystem approach to management. In the Norwegian Government White Paper “Clean and Rich Sea” (Anon. 2002), the need for better sector integration is recognised up front and the ecosystem approach is seen as the means of achieving this. The marine areas under Norway’s jurisdiction constitute parts of the North Sea, the Norwegian Sea and the Barents Sea LMEs. The description of the ecosystem approach in the White Paper is modelled very much after the framework developed for the North Sea. Development of the ecosystem approach for the Barents Sea The Norwegian Government started a process to develop a management plan for the Barents Sea in 2002. The development of the plan is now in its final phase, and it will be presented for the Norwegian Parliament this spring. The plan includes development of EcoQOs and assessments of the key sectors that impact the Barents Sea ecosystem, which are fisheries, mariculture, offshore oil and gas activities, shipping, long-range transport of pollutants, and climate change. 6 The main body for management of living marine resources in the Barents Sea is the Joint Russian-Norwegian Fisheries Commission. In the later years there has been a changing landscape of fishery management policy and this has been reflected in the work of the Commission. Attention has shifted from deciding on next years quota to deciding on long term sustainable management strategies and concern not only on the fish stocks but to the ecosystem as a whole. A common thought on the ecosystem approach is a transition from traditionally maintaining fish stocks at a healthy state to maintaining ecosystem health. This is on the background of increased activities in the Barents Sea of shipping and oil and gas exploration. It is a world wide growing concern that fishing operations should allow for the maintenance of the structure, productivity and diversity of the ecosystem on which fisheries depends. Two elements are pointed out as indicators for ecosystem health: Biodiversity Pollution The ocean floor is increasingly recognized as an important reservoir of marine biodiversity. There are at present planned joint Norwegian /Russian investigations on benthic habitats and species structure in the Barents Sea. The use of certain fishing gears or practise can have harmful impact on species and bottom habitats in some areas. There are at present area/time restrictions for certain fisheries in the Barents Sea in order to protect young individuals of commercial fish species. These restrictions can be categorized as temporarily marine protected areas (MPA), and can be developed further as a useful tool on the way towards an ecosystem approach. The following elements are relevant: Rebuilding overexploited fish stocks Preserving habitat and biodiversity Maintaining ecosystem structure Buffering against the effects of environmental variability Serving as a control area (population parameters on exploited groups in some areas can be compared. 7 The fishing industry in the Barents Sea is dependent on a non-polluted Barents Sea when selling the products. On a background of increased activities of shipping and oil and gas exploration, it is important that the pollution state is monitored regularly to document the “clean” status of the Barents Sea. Institutional implications As we see it, the ecosystem approach has institutional implications on the way science and scientific are produced. Therefore, the Board of IMR initiated in spring 2002 a process to develop a new organization and way of functioning for the institute. The introduction of the ecosystem approach in the White paper from the Norwegian Government, in the Bergen Declaration from the 5th North Sea Conference, and the new strategic plan for ICES were important triggers and motivation for the reorganization. During a 1.5-year internal process lead by the leader group extended with representatives from the major labour unions, a new organisation was developed (Misund et al. 2006). The new organization has three ecosystembased and one thematic science and advisory programs, nineteen research groups, a technical department divided into nine research technical groups, an administrative department extended with the former centre administrations, and an unchanged research vessel department to operate the research vessel fleet of the institute (Fig. 4). The about 200 scientific employees make up the nineteen research groups, each with 5-25 scientists including post docs and Dr. scient. students. About 125 research technicians constitute the research technical department (Misund and Skjoldal 2005). The new organization started to function January 1st 2004. The ecosystem programs builds on a common, simplified understanding of the ecosystem approach to focus on three main themes: 1. a clean sea (monitoring and advices to secure a lowest possible level of contamination of anthropogenic pollutants in the marine environment and seafood) 2. better advices for sustainable harvest of marine resources (single species models will still be applied, but multispecies considerations and ecosystem information will be taken more account of) 8 3. reduced ecosystem effects of fishing (improve size and species selection of fishing gears and lower the impact on bottom fauna). Parts of the Barents, Norwegian and North Seas LMEs are within Norwegian jurisdiction, and Norway has the right to harvest the living marine resources within these ecosystems together with other coastal states. International cooperation at the scientific and management levels is therefore important for effective implementation of an ecosystem approach. A special responsibility of the Barents Sea program is therefore to coordinate the surveys, assessment and advisory activities with Russian interests through cooperation with PINRO in Murmansk, and to take part in the Norwegian – Russian Fisheries Commission that on a political level allocate the TAC of the fish resources in the Barents Sea. In the years to come, the objectives of the ecosystem approach to management of fisheries and marine ecosystems will be clarified and made more explicit, and we believe our new organization is well suited to deliver the scientific support for achieving those objectives. 9 Literature cited Anon. (2001) Rapport fra Havforskningsinstituttets arbeidsgruppe for økosystembasert forvaltning” (Report from the Working Group of the Institute of Marine Research on ecosystem based management, in Norwegian), Institute of Marine Research, Bergen, 32 p Anon. (2002) Rent og rikt hav, St.meld. nr. 12 (2001–2002) (Clean and rich sea, Governmental white paper, in Norwegian), Ministry of Environment, Oslo, 79 p. Available at: http://odin.dep.no FAO 2003. The ecosystem approach to marine capture fisheries. FAO Technical Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries, No. 4 (Suppl 2), 112 p Fenchel T (1987) Ecology – potentials and limitations. In: Kinne O (ed) Excellence in ecology. Book 1. International Ecology Institute, Oldendorf/Luhe ICES (2000) Report of the Study Group on Ecosystem Assessment and Monitoring, 8-12 May 2000. ICES CM 2000/E:09, International Council for Exploration of the Sea, Copenhagen, 38 p IMM (1997) Statement of conclusions. Intermediate Ministerial Meeting on the Integration of Fisheries and Environmental Issues, 13-14 March 1997, Bergen, Norway. Ministry of Environment, Oslo, 92 p. Available at: http://odin.dep.no/nsc Likens G (1992) The ecosystem approach: its use and abuse. In: Kinne O (ed) Excellence in ecology. Book 3. International Ecology Institute, Oldendorf/Luhe Misund, O.A., and Skjoldal, H.R. 2005. Implementing the ecosystem approach: experiences from the North Sea, ICES and IMR. MEPS 300, 260 – 265. NSC (2002) Bergen Declaration. Fifth International Conference on the Protection of the North Sea, 20-21 March 2002, Bergen, Norway. Ministry of Environment, Oslo, 170 p. ISBN- 82457-0361-3 10 NSTF (1993) North Sea Quality Status Report 1993. North Sea Task Force, Oslo and Paris Commissions, London, 132 p Sherman K (1995) Achieving regional cooperation in the management of marine ecosystems: the use of the large marine ecosystem approach. Ocean and Coastal Management 29: 165-185 Turrell WR (2004) The Policy basis of the “Ecosystem Approach” to fisheries management. EuroGOOS Publication No. 21, EuroGOOS Office, SMHI, 601 76 Norrköping, Sweden. ISBN 91-974828-1 11 Figure 1. Advise from ICES to the European Commission DG Environment on the division of the European seas and coastal areas into regions. These regions correspond closely to the regions or sub-regions in the proposed EU Marine Strategy Directive. 12 Framework for an ECOSYSTEM APPROACH to Ocean Management Ecosystem Ecosystem objectives objectives Adaptive Adaptive management management Advice Advice Stake-Stake holders holders Monitoring Monitoring Research Research Integrated Integrated assessment assessment Figure 2. A framework for ecosystem approach to ocean management with main components or modules shown in an iterative management decision cycle. This is a slightly simplified version of the framework in the Bergen Declaration (NSC 2002). Stakeholders should be included in the process to promote openness and transparency. 13 Types of objectives Outer boundary limits Inner target area Figure 3. Illustration of two different types of Ecological Quality Objectives (EcoQOs). Ecological quality is the overall state of the ecosystem and can only be expressed by a number of different variables or indicators for different components or aspects of the ecosystem. Operational objectives set for each of these variables or indicators can either be an outer envelope of limits or an inner envelope defining a target area for the state of the ecosystem. 14 Figure 4. The present organisational chart (tentative) of the Institute of Marine Research (IMR), following reorganisation in 2004 to be better adapted to support the ecosystem approach to ocean management.