Trigoniophthalmus alternatus (Silvestri, 1904) in Devon

advertisement

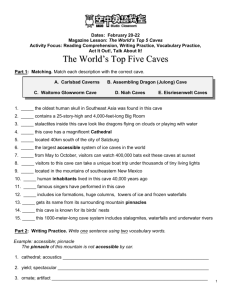

Trigoniophthalmus alternatus (Silvestri, 1904) in Devon caves Chris Proctor, 37 Grenville Avenue, Torquay, TQ2 6DS. Many people will have at least a passing familiarity with the thysaneurans (three pronged bristletails), the largest and most obvious of the apterygote (primitive wingless) insects. The familiar silverfish Lepisma saccharina, an introduced species which occurs in houses is the one most people will have come across. Seven native species are known in Britain and Ireland, five of which have been recorded in Devon (Delaney, 1954, National Biodiversity Network). The Devon species are Dilta littoralis, Dilta hibernica, Petrobius maritimus, Petrobius brevistylis and Trigoniophthalmus alternatus. The Dilta and Petrobius species are widely distributed in Britain, but Trigoniophthalmus alternatus is restricted to south Devon, making it of considerable interest from our point of view. T. alternatus is at the northern edge of its range here – elsewhere it is widespread in continental Europe (except Scandinavia) and it also occurs in the northeast USA, where it is though it may have been introduced (Fauna Europaea database, Wygodzinsky and Schmidt, 1980). While the thysaneurans as a group are instantly recognisable, identification to species is not so easy. However with care, field identification to genus is perfectly possible, and with Trigoniophthalmus this is all that is necessary, as we have just the one species in Britain, T. alternatus. In common with other thysaneurans, Trigoniophthalmus alternatus is quite a large animal, with a body length (not including the tail) of up to 10mm. It is brown in colour with irregular paler patches, and often adopts a peculiar angular hunchbacked pose that is well shown in figure 1. This may prove to be a useful field character but further observations are needed. The antennae are about the same length as the body, or a little shorter (they are longer than the body in Petrobius, and Dilta has antennae much shorter than the body). However the antennae are frequently broken, especially on older individuals so this is not a reliable character. The eyes are the most useful diagnostic feature. Trigoniophthalmus has a pair of large, circular compound eyes, with a pair of small subtriangular ocelli, lying close together in front of them (figure 2). Petrobius has large circular compound eyes, with large slit like ocelli in front of them, almost as wide as the compound eyes (figure 2). In Dilta, the compound eyes are rectangular, with small ocelli in front of their outer corners (figure 2) (Delaney, 1954, Wygodzinsky and Schmidt, 1980). Delaney (1954) gives Berry Head, Brixham as the only British site for Trigoniophthalmus alternatus but provides no other details (other than that it is “very rare!”). Members of the Cave Research Group subsequently found it in caves in the Buckfastleigh, Yealmpton and Plymouth districts between 1965 and 1973 (Hazelton, 1967, 1978). There appear to be no more recent published records. The National Biodiversity Network database lists only the Berry Head grid square (SX 9456) with no details of date or finder – presumably Delaney’s old record. In 2005, I investigated invertebrates in various Devon caves and found thysaneurans at two sites at Brixham and Buckfastleigh, sufficiently far inland to suggest that the species involved was not Petrobius – a common genus on coastal rocks, which can often be found in sea caves. Large scale macro photos were obtained and at both sites the animals proved to be Trigoniophthalmus alternatus. These two caves are new site records for the species. At both the Brixham and Buckfastleigh sites T. alternatus was found on dry, vertical to overhanging rock walls in the cave threshold – the twilight region a few metres in from the cave entrance. They seem to prefer spots in the deep threshold, near the limit of light penetration, sometimes occupying shallow fissures, but frequently on flat rock. They are not abundant at either site – only two or three have been seen on any one visit. The old Cave Research Group records (Hazelton, 1967) give the habitat as the deep threshold at one site, and the dark zone at another, though the latter cannot have been very far from the entrance as the cave it was found in is only 13 metres long. The sites chosen are much the same areas favoured by other characteristic cave threshold fauna such as the cave spider Meta menardi. In 2005 T. alternatus was first seen at the Brixham cave in early January. A visit to the cave in May to try to obtain better photos failed to locate any specimens. Many visits were made to the cave near Buckfastleigh from May onwards (a topographic survey was carried out over the summer of 2005) and although a lot of other fauna was found, T. alternatus was not seen at this site until mid October. A visit to the Brixham site in late November revealed that it had reappeared in that cave. The Cave Research Group records (Hazelton 1967, 1978) of T. alternatus in caves date from the winter period between November and March. Taking these records together, T. alternatus seems to be present in caves over the winter but disappears over the summer months. This suggests that the species may use cave thresholds as hibernation sites. The habits of T. alternatus in the northeast USA are described by Wygodzinsky and Schmidt, (1980). There, it lives almost exclusively on rocks, generally in disturbed areas such as old walls, under rocks and in limestone quarries. They hide during the day and emerge at dusk, appearing only for a short period after sunset, around twilight. “Hundreds of specimens” are described as milling around on top of a stone wall at Cornell University at twilight. If the animal has similar habits in this country, then in summer it must presumably disperse from its hibernation sites to adjacent rock outcrops, where it could be searched for after sunset. In addition to searching outcrops near caves, it would be well worth checking other rock outcrops, walls etc – it is likely that T. alternatus hibernates not only in caves but also in small cavities of mesocavernous dimensions among rocks, in screes, and in walls. I would be very interested in any reports either of confirmed or suspected presence of T. alternatus at any further Devon sites. Thysaneurans on coastal rocks and in sea caves are likely to belong to the common coastal genus Petrobius, but at present if thysaneurans are found at any inland cave in Devon, then T. alternatus should be suspected. Given its rarity, specimens of T. alternatus should obviously not be collected from any of its Devon sites. As noted above, the animal can be identified in the field either by taking a good macro photo showing the eyes (although a reproduction ratio of at least 1:1 is really required) or by examining the animal with a good hand lens or field microscope. Even if not identified to genus, any record of thysaneurans in an inland cave would still be valuable. I can be contacted at the above address. References. DELANEY, M.J. 1954. Thysaneura and Diplura. Handbooks for the identification of British Insects, 1 (2). Royal Entomological society. HAZELTON, M. 1967. Biological records for 1964, 1965 and 1966. Transactions of the Cave Research Group,9 (3), 162-241. HAZELTON, M. 1978. Hypogean fauna: biological records No. 16, 1972-1976. Transactions of the British Cave Research Association, 5 (3), 164-198. WYGODZINSKY,P. & SCHMIDT,K. 1980. Survey of the Microcoryphia of the northeastern United States and adjacent provinces of Canada. American museum Novitates, (2701), 1-17. Fauna Europaea database: http://www.faunaeur.org National Biodiversity Network: http://www.searchnbn.net/index_homepage/index.jsp List of figures Figure 1. Trigoniophthalmus alternatus on cave wall, Buckfastleigh, 15th October 2005. Figure 2. (A), head-on view of Trigoniophthalmus alternatus showing the compound eyes (grey) and ocelli (black). Diagrams (B,C,D) show the arrangement of the compound eyes and ocelli in (B) Trigoniophthalmus alternatus; (C) Petrobius maritimus; and (D) Dilta sp., all viewed head-on. Diagrams (A,B,C) are drawn from photographs, (D) after Delaney (1954).