MANITOBA PSYCHOLOGIST fall 2002

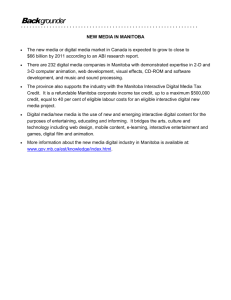

advertisement

MANITOBA PSYCHOLOGIST Vol. 21, #3, 4 Summer/Fall, 2002 THE PSYCHOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION OF MANITOBA L’ASSOCIATION DES PSYCHOLOGUES DU MANITOBA 162-2025 Corydon Avenue, #253, Winnipeg, MB R3P 0N5 204-487-0784 E-Mail: PAM@mb.sympatico.ca PAM is legally constituted by the Psychologists Registration Act (R.S.M. 1987) as the regulatory body for the practice of all branches of Psychology in Manitoba PSYCHOLOGISTS REGISTRATION ACT As noted previously in the Manitoba Psychologist, an amended Psychologists Registration Act was passed on July 6th, 2001 to bring our act into compliance with the Agreement on Internal Trade and to increase consistency in the regulation of health service providers. PAM Council, in collaboration with the Legislative Review Committee and our legal counsel, continues its work on the development of the necessary by-laws and regulations associated with the amended Act. At present, the provincial government is continuing its work on a new version of the Psychologists Act, examining how its various branches will be affected by different aspects of the Act. 35th ANNIVERSARY OF PSYCHOLOGY BECOMING A REGULATED PROFESSION IN MANITOBA submitted by Dr. Kenneth Enns, C.Psych., Member at Large, PAM Council This year marks the 35th anniversary of Psychology becoming a regulated profession in Manitoba. The Psychologists Registration Act, the original Psychology regulatory act, was prepared by an unincorporated Psychology fraternal association, the Manitoba Psychological Association, and passed by the Manitoba Legislature, in 1966. The Act came into force in 1967, with the first “registered psychologists” certified in that year. The original Manitoba Psychological Association was dissolved, and replaced by two organizations, in 1967. The Psychological Association of Manitoba was formed as the provincial Psychology regulatory organization, and the Manitoba Psychological Society was formed as the provincial fraternal organization for registered and non-registered psychologists. MPS was constituted to advance Psychology as a science, profession, and benefit to human beings. In this capacity, MPS acts as the lobbying association for the professional interests of psychologists, and also provides continuing education programs to psychologists. The Psychological Association of Manitoba was given its particular name, in part, to distinguish itself from the earlier Manitoba Psychological Association and to give it different initial letters from the Manitoba Psychiatric Association. At the time, the Manitoba government did not give the Psychology regulatory body the name of ‘Manitoba College of Psychologists,’ although its mandate was to operate as such a regulatory college. PAM has proposed that its name be changed to the Manitoba College of Psychologists in its proposed new Psychology regulatory Act, to better reflect both its legislated function and the current practice for Psychology in many other Canadian provinces. Published quarterly by the Psychological Association of Manitoba. ISSN0711-1533 This is the official publication of the Psychological Association of Manitoba. Its primary purpose is to assist PAM to fulfill its legal responsibilities concerning the protection of the public and regulation of psychology in Manitoba. It also seeks to foster communication within the psychological community and between psychologists and the larger community. Editor: Dr. Donald Stewart, c/o 474 University Centre, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N2 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF SOME OF THE CHILD PROTECTION RESPONSIBILITIES OF REGISTERED PSYCHOLOGISTS submitted by Dr. Leonard Greenwood, C.Psych., Child Protection Centre I have been asked to provide an overview of the responsibilities of Psychologists in matters where the abuse of a child is being investigated. I am happy to do so. Revisions to the Act regarding such matters and more recent guidelines to that Act warrant our attention. Areas I will note include the fact that reporting of child abuse is required regardless of when it occurred, that investigators have unrestricted access to all relevant records, and that if you report concerns you are now entitled to know the outcome of the investigation. In Manitoba, the laws defining child abuse and the requirements for professionals to respond to such situations suggestive of past or present child abuse are contained within The Child and Family Services Act of Manitoba, hereafter referred to as ‘the Act’, proclaimed 15 March 1999. There has also been published a set of guidelines to assist us in responding in a manner consistent with the Act: The Revised Manitoba Guidelines on Identifying and Reporting a Child in Need of Protection (Including Child Abuse), August 2001 (Guidelines). These, plus our own CPA Code of Ethics (COE) and companion documents, especially Practice Guidelines for Providers of Psychological Services (GPPS), are the basic reference library for professional conduct in matters regarding child protection. Defining Child Protection Issues Perhaps the first place to begin is by noting that according to the Act, a child is in need of protection “where the life, health or emotional well being of the child is endangered by the act or omission of a person’’ (part of subsection 17(1) of the Act). Therefore, how you manage your obtained information, records, observations and professional opinion are relevant for consideration under the Act. The Act and Guidelines define our legislated responsibilities when we encounter information suggesting that a child is in need of protection. Requirement to report. The first decision we often face is that of when and if to report protection concerns. According to the Act, if you as a professional (or private citizen) are led “to reasonably believe that a child is or might be in need of protection…[you] shall forthwith report the information to an [mandated] agency or to a parent or guardian of the child” (part of subsection 18(1)). There is no professional privilege in this matter. According to the Guidelines, “the duty to report applies even where the person has acquired the information through the discharge of professional duties or within a confidential relationship such as a doctor-patient relationship” (Part (1) 4). The consequences for not doing so can be significant. The Director of Child and Family Services can make a complaint to the Psychological Association of Manitoba (PAM). Conversely, if you do report in good faith, no action can be brought against you. The COE is consistent with this requirement. The COE requires that we undertake to reasonably offset threats of serious harm by reporting to those authorities who can intervene (COE II. 39), to be cognizant of the possible tension between legal requirements and the COE (COE Responsibility to Society IV.17), and to consult with colleagues when legal requirements are potentially in conflict with ethical principles (COE IV.18). We as psychologists are not mandated to conclude that a child is in need of protection, but must forward any information that would allow others to make the necessary conclusions. Reporting that a Child may be in Need of Protection Having information deemed reportable, the next question becomes: To whom does one report? At first glance, there appears to be considerable discretion. The Act suggests the professional might report to the mandated agency or to a parent or guardian. However, the Guidelines indicate that there are conditions under which reporting to a parent or guardian is not correct. The report should proceed to the agency when the parent is the cause of the problem, or the parent is unable or unwilling to protect the child. Interestingly, the parent should also not receive the report if the information leads you to believe the child might be at risk for abuse or is the target of abuse by a parent, or person in charge of the child. This clearly targets instances of intrafamilial allegations, be it in a nuclear family or stepfamily setting. Further, if you do report protection concerns to a parent, you have not completed your obligations. According to the Guidelines, if you do report the abuse to a parent and they thereafter give you reason to doubt they can or will move to protect the child, you have a continuing responsibility to report to a mandated agency. Given these caveats and conditions, I recommend that you involve a mandated agency on almost all occasions. There may be instances where you are strongly convinced that reporting your concern to a parent is a sufficient response to the Act, and is clinically the best course for your client. Even in such a case, I recommend that you review the case, in anonymous fashion, with a CFS protection worker to determine that no report to an agency is required, and then document that you have done so. Maintaining a working relationship with your client. Our sense of responsibility to our client and our ethical code (COE II Minimize Harm, III Integrity of Relationships) compels us to transform such arbitrary acts as reporting protection concerns into a collaborative activity that involves the parents of a client. However, consult with a protection worker first. If you gain an opinion from CFS that an investigation is warranted, you may also be advised not to inform the parent of your concerns. Issues relating to how to report are best discussed within two contexts -- the need to protect a child from recent or ongoing abuse, and the need to respond to failures to protect a child from past abuse. Disclosing current protection concerns. Where the information suggests there is recent or current abuse of a child, a report must be made. The Guidelines indicate we cannot inform a non-offending parent about the allegation and our reporting. In fact once the report is made we lose the power of choice regarding informing collaterals of the allegation. According to the Guidelines, “Once a report has been made, the agency assumes responsibility for informing the parent or guardian” (Part (2) 4). Ethically this is not a healthy process and it isolates us from empowering both our client and the investigative process. There exists a role for us in discussing with the client or the client’s parent how (not if) the report might be made to CFS. Before you do this, however, discuss your ideas on this matter in anonymous fashion with the CFS. Protection workers are very aware that allegations are often made impulsively or unintentionally, with ambivalence and with fear of reprisal. You may find the worker agreeable to you processing the act of reporting in a collaborative manner with your client. In practice, any groundwork that enhances the safety of the source of allegations facilitates the efforts to protect the child. In some cases, your consultation with CFS may alert you to the fact that this allegation falls in a context of chronic issues or additional protection concerns. In such cases, collaboration may be a lesser issue. In all cases where you do act in collaboration regarding reporting, do not conduct an investigative interview. Such interviews are mandated to others. Your investigative behavior may compromise their work and the protection of a child. Some of the angst and concern regarding the impact that our reporting of these allegations might have on our client can be prevented. When beginning any work with a client, advise the client regarding the limits of confidentiality (GPPS III.1, V.2, & V.3). In some cases, especially where disclosures can be anticipated, consider undertaking a detailed discussion of how you and the client (if an adult) might fulfill your shared responsibilities in this regard. Disclosing historical abuse. I wish to anchor this discussion by making a point of distinction: The perspective on past allegations considered here is not that of calling a perpetrator to account for harm done, nor assisting a survivor adjust to past maltreatment. Descriptions of criminal acts are a police matter. The focus here is only on the question, Does information provided indicate a child is or is likely to be harmed? When the information we obtain points to past abuse rather than the present need for protection of a child, we may anticipate some room for judgment regarding reporting (e.g., if COE II.39 ‘duty to protect’ is not applicable). However, the Guidelines are clear. Situations where past abuse is reported are to be handled in the same way as those alleging current abuse (Guidelines Part (2) 6). There is no stated statute of limitations on our onus to report in this regard. In talking to authors of the Guidelines, they point to concerns that alleged perpetrators of historical abuse may still be harming other children. They urge that the psychologist consult with a mandated agency regarding whether material is reportable. As clinicians, current practice might lead us to leave the decision regarding reporting to our client. For example, an adult client may recall abuse but not feel able or yet ready to make public the facts of their victimization. Such a practice does not conform to the Guidelines and perhaps our profession might advocate for clarification on this point. The Guidelines do not stand alone in opposition to this practice. The COE notes that the consideration of consequences to others requires we disallow certain client rights. The law has given the opinion that allegations, once made, have consequences for others that take priority, and we are not the ones charged with determining the seriousness of those consequences. It would seem prudent where past abuse is alleged for clinicians to take the following steps: 1. They record in detail the allegation, including the identity and present location of the offending person. If possible, gain some idea whether the offending person continues to be in a position where they can abuse children. 2. Discuss with your client whether they have previously reported the abuse and their concerns about doing so now. Explore any fears they have that reporting the abuse will result in harm to themselves or others. 3. Consult anonymously with CFS and a colleague regarding the significance of the report and the potential need to protect. Document that you have done so. 4. Unless explicitly directed otherwise by CFS, inform the client of your ethical opinion and make an effort to address the reporting issue collaboratively. These decisions require a careful and documented evaluation on a case-by-case basis. Arbitrary decisions may compromise your client, your relationship with your client, or fail to protect others from present or future harm. In this case both responsibilities to the client and to society need to be measured. Confidentiality and Clinical Documents There are specific rules regarding confidentiality when there is a question of a child in need of protection. In the context of a child protection investigation, the CFS agency, the police, and medical personnel have mandated responsibilities that require exchange of information without a client’s consent: “[T]here shall be mutual sharing of all relevant information by the agencies and professionals involved” (Guidelines Part(3)). The Child and Family Services Agency is required to arrange for medical and police involvement and “to share all relevant information of a confidential nature” (Guidelines Part (3) 1). There are no exceptions with regard to the requirement to provide information. The Act supersedes all other provincial legislation. For example, the Personal Health Information Act (PHIA) subsection 22(2) allows for disclosure of information without consent if required by the Act. Our own COE requires you share confidential information when required by law (COE Responsible Caring I. 45). Those mandated can request your documents where relevant. It is therefore recommended that you obtain in writing their request for information, but you cannot stall, edit, or limit their access to your records. I recommend that you maintain your standard of recording such that no question can be raised about uneven documentation of protection-related concerns (COE I.37 & 39). If an individual gives you a disclosure suggestive of abuse, record it in detail, even if it is tangential to your treatment purpose. The COE (IV.25) requires that we ensure our information does not mislead, and is not misunderstood by, mandated agencies. We have a responsibility to promote the fair treatment of our client, and to ensure that confidentiality rights are maintained in other areas (Encourage Dignity of Persons). Thus, where the information provided would in your judgment require professional training in order to provide appropriate understanding, inform the Agency of that opinion and offer such understanding in the interest of protecting your client. The Role of Psychologists in Child Protection Investigations There is a role for a Psychologist in a child protection investigation. The Guidelines note that the agency may need to collaborate with ‘others’ (e.g., psychologists) in gathering evidence to establish “a serious and persistent pattern of abuse likely to cause emotional disability of a significant nature” (Part (3) 4). Such a professional opinion is necessary for the agency to defend acting to protect a child from emotional abuse. If you have professional training to make such an assessment, this may be a role you could undertake, as part of the investigation. For several ethical reasons, be very cautious about making opinions regarding emotional abuse if you are involved in another relationship (e.g., therapist) with the child who is the subject of investigation, or with the individual who is the target of suspicion. Avoid dual relationships. It is likely ethically wiser to defer responding to a request for such an opinion because you cannot have both the child and the mandated agency as your client. That does not mean you should remain silent. You may be in a sound position to give an opinion regarding that child’s emotional health and the current level of parenting care required by this child. If you are treating an adult for mental health issues and that adult is a parent, then questions regarding the impact of the treatment issue on parenting are germane. I maintain that you have an obligation to survey this area and respond accordingly (COE I.47 Respect for Dignity of Persons, Extended Responsibility). If mental health issues are impacting on parenting, contacting CFS may generate a collaborative supporting response (e.g., using support homemakers, engaging alternate significant adults to help) that pre-empts the need to act in a mandated fashion. Conclusions of the Investigation Something new, and welcome, is the closure of the feedback loop regarding the reporting of protection concerns to the agency. According to the Guidelines, once an investigation has been concluded, you as the person who initiated the investigation through your report should receive notification of the agency’s conclusion (Part 4 and Act section 18.4) that the child was or was not in need of protection. Province of Manitoba (March 1999) The Child and Family Services Act of Manitoba. Winnipeg: Author. Thank you for this opportunity to review some issues for psychologists regarding our response to issues of child protection. I see us as active partners with other professionals in attending to the protection issues that are either manifest or latent in almost every child and adult mental health client situation. In preparing this document, I surveyed some Winnipeg Child and Family Services protection workers regarding their working relationship with psychologists in general. While they had general concerns about the cooperation they garnered from other professionals, they reported psychologists to be generally responsive to their enquiries. It is gratifying to have such respect reflected in their comments. The working relationship between mandated workers and other professionals has such potential for distortion that it begs discussion in another forum. As members will recall, the Examination for Professional Practice in Psychology has moved from its traditional twice a year paper and pencil administration schedule to an on-demand computer-administered version available locally through Sylvan Learning Centres. It is more expensive for the Professional Examination Service to develop, maintain, and administer the test in this fashion, and as a courtesy to examinees PES has been phasing-in these increased costs over a two-year period. For additional information about topics raised in this article, contact Dr. Greenwood at 787-4563 or via e-mail: LGreenwood@exchange.hsc.mb.ca References Canadian Psychological Association (2000) Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists – Third edition. Ottawa: Author. Canadian Psychological Association (1989) Practice Guidelines for Providers of Psychological Services. Ottawa: Author. Province of Manitoba (2001) Revised Manitoba Guidelines on Identifying and Reporting a Child in Need of Protection (Including Child Abuse) Winnipeg: Author. EPPP FEES TO INCREASE SUBSTANTIALLY IN DECEMBER Locally, we have been benefiting additionally because our members have been charged in Canadian dollars at par with U.S. dollars for the EPPP. As of December, 2002, however, PAM has been informed that our costs will no longer be covered at par. This means that the cost of the exam will increase substantially to $450 U.S. (exam fee), along with a $65 U.S. administration fee to Prometric, which is contracted to deliver the tests through Sylvan Learning Centres. If you have any questions about the EPPP or these fees, please contact the Registrar at 487-0784. Please note that PAM does not make any money on the administration of the exams. We are charged the fees as noted above, which we are then responsible for collecting from members or candidates who take the exam.