Departmental Grant Writing Retreats: A Strategy

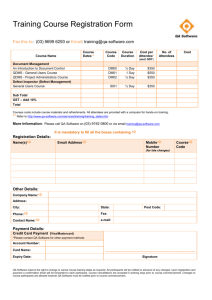

advertisement

version 052809 ka Departmental Grant Writing Retreats: A Strategy for Obtaining and Maintaining Successful Research Funding in Clinical Departments Kurt H. Albertine, Ph.D.,1,2 James F. Bale, Jr. M.D.,1 J. Michael Dean, M.D., M.B.A.,1 and Gary C. Schoenwolf, Ph.D.1,2 1 2 Department of Pediatrics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84158 Department of Neurobiology & Anatomy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84132 Running Title: Departmental Grant Writing Retreats Key Words: Physician-scientists, career development, research funding Address correspondence to: Kurt H. Albertine, Ph.D. Department of Pediatrics Division of Neonatology University of Utah Health Sciences Center Williams Bldg Salt Lake City, Utah 84158 TEL: (801) 581-5021 FAX: (801) 585-7395 E-Mail: kurt.albertine@hsc.utah.edu Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats ABSTRACT This report describes a unique strategy for preparing junior faculty and fellows in clinical departments for the rigors of applying for grant support. Since 2002, the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah has conducted biannual weekend retreats that cover key elements of successful grantsmanship for departmental junior faculty and fellows. The goal of the retreat is to provide tools for strengthening each attendee’s grant-writing skills through a combination of didactic discussions, detailed one-on-one critiques of each application, and hands-on guidance in the reshaping of each application. The retreat emphasizes the main components of National Institutes of Health (NIH)-templated grant applications. A series of brief, focused didactic sessions on specific aims, background and significance, preliminary studies, research design and methods, statistical framework, budget, key personnel, and protection of human subjects and experimental animals are presented. The majority of attendees’ time is spent revising the sections of their grant application, after obtaining detailed critiques from experienced senior faculty investigators. The retreat ends with a mock study section that provides each applicant with a glimpse into the process of grant review, as well as providing them with hands-on experience in critiquing grant proposals, again under the guidance of senior faculty members. Since 2002, sixty attendees have submitted 131 proposals to intramural or extramural foundations, NIH, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or industry. Of 23 applications submitted by attendees to the NIH, 12 have been funded, including three K08s, two K23s, one K24, one R03, two R21s, and three R01s. Based on our experience, we suggest that departmental grant writing retreats are an effective strategy for improving the research portfolios of clinical departments. 2 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats INTRODUCTION Submitting successful grant applications remains one the most important measures of scholarly activity in academic departments 1. For tenure-track faculty, receiving extramural grant support is usually a major criterion for judging a candidate’s suitability for promotion and tenure. Moreover, the granting process supports scientific discovery into human disorders. Although department chairs and faculty recognize the importance of successful grant applications, few departments allocate specific resources to this process beyond the traditional “three years” of protected time given to new faculty recruits. Moreover, pediatric fellowships infrequently provide focused training in the process of applying for grants. In 1990, the Department of Pediatrics conducted a weekend retreat for junior faculty to develop grant applications as part of a faculty development grant in general pediatrics. Since 2002, the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah has resurrected biannual weekend retreats for its junior faculty and fellows. During the two and one-half days of the retreat, experienced senior faculty investigators lead brief, focused didactic discussions on the parts of a grant application, using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) application as the template. Major topics include specific aims, background and significance, preliminary studies, research design and methods, statistical framework, budget, key personnel, and protection of human subjects and experimental animals. Attendees devote the majority of their time revising their grant proposal. Senior faculty members provide one-on-one critiques throughout the weekend, emphasizing the importance of well-conceived and well-written sections that “sell” the science. A major goal of the retreat is to encourage talented faculty that it is feasible and possible to write successful grant applications, despite the competitive nature of the process. The overall success of the grant writing retreats can be measured by the success of the submitted grant 3 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats applications. Of 23 NIH applications submitted by Department of Pediatrics attendees, 12 have been funded to date. RETREAT OVERIEW Venue and Logistics Grant writing retreats are held in November and April at a local ski resort during the "off season", enabling low rates with a charming setting. The dates, selected, in part, to correspond to grant cycles for the Primary Children’s Medical Center Foundation, allow attendees ample lead time to prepare applications for the traditional February and June cycles of the NIH. The dates also allow the Department to take advantage of reduced rates during the low-occupancy seasons at Utah’s ski resorts. The venue is arranged much like study section: a series of tables set up in a rectangle to provide a comfortable writing space and to allow ample interaction of attendees with faculty and their peers. The venue provides wireless access to the internet, and attendees have access to power outlets for laptop computers; a laser printer is provided for group use. Also included among the teaching aids are textbooks on writing and graphic arts. Each attendee is relieved of clinical responsibilities for the weekend (Friday-Sunday) of the retreat. This requires the support of division chiefs, especially in small or busy divisions that rely heavily on faculty or fellows for clinical coverage. Each attendee is provided a condominium room at the lodge. Although attendees are required to be at all of the didactic sessions, attendees may use their rooms for additional quiet-writing space. However, nearly all 4 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats attendees prefer to remain with the group to take advantage of the one-on-one interactions with senior faculty. Each attendee may bring their family members, including children, and rely upon his or her spouse or significant other for child care during the retreat. This strategy reinforces the concept that grant writing requires protected time, but also acknowledges that this process occurs in the context of a faculty member’s life and responsibilities. Meals are provided at lunch and dinner on Friday, breakfast and lunch on Saturday, and breakfast on Sunday. Attendees, families, and senior faculty eat together, cafeteria-style, a strategy that promotes ongoing discussion among attendees and senior faculty. The on-your-own dinner on Saturday night provides an opportunity for smaller groups of attendees, faculty, and families to enjoy a meal together at neighboring restaurants and helps bond attendees and faculty in a research community. Schedule The weekend schedule is constructed around the sections of the NIH application and includes a mock study section on the final morning. The typical schedule is shown in Table 1. Didactic time is limited to key elements so that the majority of the attendee’s time is used for writing, feedback, and revision. Published Resources The retreat uses several published resources 2-5, including the classic Elements of Style by Strunk and White 6 and Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers by Zeiger 7, to teach effective writing techniques. Attendees learn to avoid passive voice, nominalization, run-on 5 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats sentences, noun clusters, dangling participles, and the like. Attendees leave understanding why “We found that…” or “The drug increases…” are more powerful than “It was found that…” or “The drug results in a change…” Although such concepts were undoubtedly learned in high school or college, years of hurriedly writing patient-care notes undermine the writing skills of most physicians. CONTENT Introduction to Grant Writing The intent of this didactic session is to welcome attendees to the retreat, introduce the attendees and senior faculty to one another, provide an overview of the mechanics of the retreat and venue, and emphasize that research is a critical mission of the Department of Pediatrics. In regards to the latter, research and grant proposal writing are stressed as high priority for the department, and that senior faculty are committed to helping junior faculty and fellows succeed in this process and their career development. The retreat faculty emphasize that the first impediment to be overcome is the junior faculty member's perception that obtaining a grant is impossible. Because the weekend involves intensive criticism of each attendee’s grant proposal, the introductory session emphasizes that the objective of the intensive criticism is to help each attendee write the best possible application, not to criticize for the sake of criticism, and that the senior faculty are willing to work constructively with each attendee to achieve this goal. Specific Aims The intent of this didactic session is to emphasize the importance of having a good idea to explore in a grant proposal, and to “sell” the significance of this idea to the grant review panel 1, 6 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats 8, 9 . This session includes a discussion of what is a hypothesis and how one goes about directly testing this hypothesis. Typically, most of the weekend focuses on the re-crafting of this section based on the idea that the Specific Aims page provides “the bait on the hook” because this section of the proposal is its cornerstone. If the bait does not lure the reviewer, the grant proposal is unlikely to be recommended with enthusiasm and thus unlikely to be funded. This quintessential function is also shared with the Abstract section 10. An adage that we use for the Abstract section is “you get only one opportunity for a first impression, so don’t blow it!” The Abstract should stand alone from the rest of the grant proposal, including the Specific Aims section, and emphasize the importance of the proposal. Background and Significance The intent of this didactic session is to provide a roadmap for composition of the “Background and Significance” section. The notion conveyed is that the applicant is a story teller whose responsibility is to bring readers to a common level of knowledge so that they understand the focus of the proposal and how the proposal will impact the field 1, 8, 9. To provide focus, attendees are guided to use key words in the context of the specific aims of their proposal to sell the hypotheses that will be directly tested in the “Research Design and Methods” section. By so doing, the applicant shows her/his familiarity with the field by highlighting the relevant (as opposed to all) literature and understanding its meaning. Thus, the flow of this section is from context, to knowns, to unknowns and/or controversies. By identifying the relevant unknowns that the proposal will address, the applicant will be in a better position to identify the utility of their results for advancing the field. In this regard, essential questions to be answered in this 7 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats section are: “does the proposal address an important problem”, and “how will the answer(s) move the field forward?” Preliminary Studies This didactic session conveys that the “Preliminary Studies” section’s purpose is to demonstrate feasibility of completing the specific aims, as developed in the “Research Design and Methods” section of a grant application 1, 8, 9. In other words, this section sells the Principal Investigator and the environment. Recommendation is made to include schemas, cartoons, pathways, etc., because of the economy gained by a picture. However, the picture must be clear 11 ! Another benefit of inclusion of graphic artwork is that it breaks up the monotony of text, text, text 4. In this context, the attendees are reminded that reviewers, too, are tired, have bad days, and have lives outside the workplace. Therefore, reviewers appreciate when an applicant provides informative, accurate pictures from which reviewers “get” what the applicant proposes to pursue. Demonstrating feasibility is a key goal of this section, for each specific aim! To attain that goal, the applicant should demonstrate that they have the tools and reagents to obtain the intended results, and that the applicant and investigative team have the necessary expertise to conduct the proposed studies. As a general rule, new investigators or investigators moving into a new field will find that more preliminary data are helpful. As another general rule, the greater the ambitiousness of a proposal, more preliminary data are needed. This didactic session concludes with the notion that the “Preliminary Studies” section will be stronger if it provides balance and parallel construction with the “Specific Aims” section (each Specific Aim, in the same order), “Background and Significance” section (importance of the proposal’s results to the 8 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats field), and “Research Design and Methods” section (to support the feasibility of performing the proposed experiments). Research Design and Methods, and Statistics One goal of this didactic session is to provide guidance for composing the “Research Design and Methods” section of a grant application. This section, unlike the “Background and Significance” and “Preliminary Studies” sections, is written in future tense because the applicant is asking for support for studies that will be performed. In contrast, the previous two sections are written in past tense (active past tense, preferably) because the studies and results that are described in the grant application have been performed. Key elements to include in this section are (1) provide a big-picture overview of the study and its design, (2) copy and paste the Specific Aims so that reviewers do not have to hunt for them, (3) for each Specific Aim, provide an overview of the experimental design and its value, anticipated results, and pitfalls, limitations and alternative approaches, (4) statistics, (5) time table, (6) a brief impact summary, and (7) finish with detailed procedures 1, 8, 9. A helpful inclusion in the big-picture element is to provide a flow diagram or cartoon. Advice to gain economy of space to cite methods that the investigative team has published. If the applicant and investigative team do not have expertise or reagents, the applicant is encouraged to recruit collaborators and include their letters of support in the application. The rationale for considering pitfalls, limitations, and alternative approaches is that reviewers understand that no study design is perfect. Therefore, reviewers look for signs of competency, which are reflected by self-critical evaluation, and problem-solving ability. Another goal of this didactic session is to review the essential elements of protection of human subjects and welfare of experimental animals. The attendees are reminded that they are 9 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats obligated to comply with approval requirements because without them, a grant application may become derailed, even if ranked as meritorious by study section. Another topic that is discussed is inclusion of women, children, and minority/ethnic groups, and how to write about limitations of inclusion. The final goal of this didactic session is to provide an overview of statistical considerations. Most importantly, the attendees are encouraged to engage a statistician during the design phase of a research project so that topics such as power analysis and identification of appropriate study design for valid statistical analysis do not become issues during review. Career Development Awards The didactic sessions conclude with a discussion of career development awards, especially the K series awards available from the NIH. This session provides information regarding the types of K awards and their eligibility requirements 12. During the discussion, attendees learn that key elements in this process include the selection of mentors, attention to the career development plan, and the importance of the departmental commitment to their grant and their careers. Attendees, especially those with advanced scientific training, are encouraged to utilize a “gap-based” approach to their career development by identifying their critical areas of need and how the award will fill the gaps and facilitate their development as leaders in scientific investigation. Mock Study Section The purpose of this interactive session is to help the applicants “see” how their application may be judged by a review panel - an eye-opening experience for most junior faculty 10 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats and fellows. Using only the Specific Aims page of each application, primary and secondary reviewers are assigned from the pool of attendees. Each attendee serves as an applicant for one grant proposal, a primary reviewer for one of their peer’s proposals, a secondary reviewer for another of their peer’s proposals, and a panel member for each proposal. The applicant remains in the room when his/her proposal is reviewed, but reviewers are not allowed to directly address comments or questions to the applicant, and the applicant is not allowed to participate in the discussion. The primary reviewer has 5 minutes to present the application to the panel and to critique it. The secondary reviewer has 3 minutes for follow up, and the panel discussion occurs for an additional 5 minutes or so. MEASURES OF EFFECTIVENESS An important goal of the retreat is its emphasis on overcoming the writer’s block that affects many physician-investigators. Although medical school, residency, and fellowship training provide superb clinical preparation, most physicians do not leave these segments of their training with adequate writing skills. Ironically, writing ability and motivation to write are not directly assessed when new faculty are recruited. The more than 100 grant applications submitted by 60 attendees of our grant-writing retreat since 2002 suggests that this goal has been achieved by providing protected time to initiate this activity in a cloistered setting free of typical daily interruptions. An important measure of the success of a grant writing retreat is its return on investment. Since 2002, nearly 60 junior faculty or fellows of the Department of Pediatrics have attended the grant writing retreats. Of these, 38 junior faculty or fellows subsequently submitted 131 grant proposals to a foundation, NIH, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or industry. Of 11 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats the 131 applications, 25 were submitted to the Primary Children’s Medical Center (PCMC) Foundation. This Foundation provides up to $25,000 per award per year as a means to support the beginning research careers of junior faculty or fellows. Sixteen of the 25 applications (64%) were funded, corresponding to direct costs of $371,381. The PCMC foundation, recognizing the benefit of the grant writing retreats, now underwrites the cost of the retreats and requires that applicants attend the retreat before submitting their proposals. Ninety-six grant proposals have been submitted by attendees to funding agencies other than the PCMC Foundation. This includes 27 proposals to the NIH since 2002. Of these, 12 were funded (including three K08s, two K23s, one K24, one R03, two R21s and three R01s). The funded awards correspond to >$6,000,000 in direct costs. Given that the retreats cost approximately $12,000/retreat, the return on investment during the 5 years of the retreats (nine, to date) is nearly 60:1. SUMMARY Based on our experience, we conclude that the departmental grant writing retreats are an effective strategy for improving the research portfolio of our department. From the attendees’ perspective, they gain knowledge that they should write for the readers/reviewers 1, 8, 9 . The attendees also learn to write concisely, format and edit thoughtfully and carefully, and to use figures that enliven what can become deadly wastelands of endless text. Furthermore, they learn that having trusted, knowledgeable colleagues read one’s grant application is an important step in avoiding embarrassing technical mistakes or typographical errors. Attendees learn that such mistakes should not be found at study section, especially given the current exceedingly competitive funding environment. 12 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats The retreat requires an ongoing supply of attendees. In this regard, the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah has grown the number of departmental fellows from 10 fellows in 1995 to >40 in 2009. During the same period, the faculty growth increased from approximately 106 faculty members to nearly 240. Most fellows attend at least one grant writing retreat during their fellowship training, in addition to attending their required fellows’ curriculum, which emphasizes research ethics, statistical design, and scientific communication skills. The retreats also require a critical mass of experienced senior faculty committed to mentoring and young investigator career development. The senior faculty must set aside their own activities in favor of mentoring their colleagues and successors. We have found that an optimum ratio is about 1-2 attendees (junior faculty, fellows) per senior faculty; this necessitates limiting the number of attendees to 12-14. This high senior faculty-to-attendee ratio enables senior faculty to critique proposals one-on-one with each attendee. This process enables attendees to overcome another block in effective grantsmanship: one’s ego regarding personal writing style. By experiencing several critiques during the course of the weekend, attendees gain a sense of what constitutes clear writing in the eyes of the reader, as well as the effort required to compose a meritorious grant application. Each attendee leaves with the clear understanding that “you will never get a grant if you don’t apply”. 13 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Edward B. Clark, M.D., Professor and Chairman, Department of Pediatrics, for the foresight and commitment to improve the competitive position of junior faculty and fellows in our department. We also thank Primary Children’s Medical Center Foundation for the financial support that makes the biannual retreats possible. Thanks are also extended to our colleagues in the department who give their time and effort to serve as retreat faculty, including Robert H. Lane, M.D., Carrie Byington, M.D., Amy Donaldson, M.S., and Jackie Hinton. We thank Kathy Boyer, Jan Johnson, and Sheri Carp for organizational support for the workshop. 14 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. Todd RF, 3rd, Miller DM, Silverstein RL. Hematology grants workshop-2001. Hematology American Society and Hematology Education Program. 2001:507-521. Browner W. Publishing and Presenting Clinical Research: Williams & Wilkins; 1999. Zinsser W. On Writing Well. Third ed. New York: Harper & Row; 1988. Gitlin L, Lyons K. Successful Grant Writing. Second ed: Springer Publishing Company; 2004. Truss L. Eats, Shoots & Leaves. Vol 1. first ed. New York: Gotham Books; 2003. Strunk W, White EB. The Elements of Style. third ed. Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon; 1979. Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Rsearch Papers. Second ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000. Inouye SK, Fiellin DA. An evidence-based guide to writing grant proposals for clinical research. Ann Intern Med. Feb 15 2005;142(4):274-282. Chung KC, Shauver MJ. Fundamental principles of writing a successful grant proposal. Journal of Hand Surgery [Am]. Apr 2008;33(4):566-572. Bordage G, Dawson B. Experimental study design and grant writing in eight steps and 28 questions. Med Educ. Apr 2003;37(4):376-385. Briscoe MH. Preparing Scientific Illustrations. Second ed. New York: Springer; 1996. Bodine DM. Hematology grants k08 and k23. Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2005:538-542. To be added: McCabe LL, McCabe ERB. How to succeed in academics. American Medical Association. Manual of Style. 9th edition, Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, 1998. (ISBN 0-683-40206-4). 15 Albertine et al., Departmental Grant Writing Retreats Table 1: Typical Schedule Day Hour Activity Friday 9:00 AM 10:00 AM 10:15 AM 11:00 AM Noon 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 5:00 PM Check-in Introduction to the weekend’s format Introduction to grant writing and “Specific Aims” didactic session Writing and revising time Lunch with families “Background and Significance” didactic session Writing and revising time Dinner with families Saturday 7:00 AM 8:00 AM 9:00 AM Noon 1:00 PM 2:00 PM 4:00 PM Breakfast “Preliminary Studies” didactic session Writing and revising time Lunch with families “Research Design and Methods”, and statistics didactic session Writing and revising time Submitting an NIH grant, including budget guidance and writing career development plans for K’s, didactic session Dinner and free time with families 6:00 PM Sunday 7:00 AM 8:00 AM 11:00 AM Noon Breakfast Mock Study Section Wrap-up Check-out 16