Notes_for_Guest_Lecture

advertisement

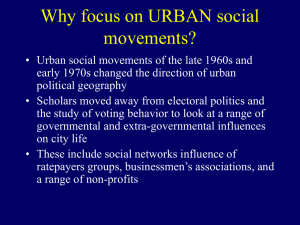

Notes for Guest Lecture Global Development and Underdevelopment Spring Term, Academic Year 2007/2008 Session 7 - 10th March 2008 Globalisation and Marginalisation: Social Movements in South Africa This lecture provides an overview of central issues in the study of contemporary social movements. By focusing on the social movement terrain in South Africa, we will discuss the twin themes of globalisation and marginalisation as they play themselves out in Africa’s richest country and one of the world’s most unequal societies. 14 years after democracy, the country today has more protest actions than anywhere. Which issues do such social movements address and why have they emerged? Are their struggles ‘global’ or ‘local’? How do globalisation and development manifest themselves in South Africa? Key Readings Patel, Raj (2006) A short course in politics at the University of Abahlali BaseMjondolo. Centre for Civil Society Research Report No. 42. Durban, University of KwaZulu Natal. Philani Zungu (2007) DEMOCRACY IN MY EXPERIENCE (attached) Other Reading The Durban-based Centre for Civil Society has an excellent online library of research reports, links and other resources on social movements in South Africa and beyond: www.ukzn.ac.za/ccs/ Ballard, Richard, Habib, Adam & Valodia, Imraan (2006a) Social movements in South Africa: pomoting crisis or creating stability? IN PADAYACHEE, V. (Ed.) The development decade? Social and economic change in South Africa, 1994-2004. Cape Town, Human Sciences Research Council. Castells, Manuel (1997) The power of identity, Cambridge, Mass. ; Oxford, Blackwell Publishers. Crossley, Nick (2002) Making Sense of Social Movements, Buckingham, Open University Press. Desai, Ashwin (2002) We are the poors. Community Struggles in Post-Apartheid South Africa, New York, Monthly Review Press. Edwards, Gemma (2004) Habermas and social movements: what's 'new'? IN ROBERTS, J. M. & CROSSLEY, N. (Eds.) After Habermas: New Perspectives on the Public Sphere. Oxford, Blackwell. McKinley, Dale (2006) Democracy and social movements in South Africa. IN PADAYACHEE, V. (Ed.) The development decade? Social and economic change in South Africa, 1994-2004. Cape Town, Human Sciences Research Council. Pilger, John (2006) Freedom Next Time, London, Bantam Press (the chapter on South Africa) SA political economy By way of an introduction to the country, I would like to give you just a few figures on poverty, income distribution, GDP and so on. There are very high levels of inequality in the country. Indeed, according to figures released just last week, the Gini co-efficient for the country is 0,72, which is the highest or 2nd highest score in the tables, dependent on which statistics you look at. And this figure does not capture inequality amongst particular groups, e.g. amongst black people. It is always difficult to imagine what such figures actually mean; let me try and illustrate. Gauteng, the smallest of the SA provinces, home to Johannesburg and Pretoria, produces 10% of the GDP of the entire African continent, and 1/3 of SA’s GDP. In terms of its international ranking of GDP it is ranked 55; but on the HDI it is only ranked 121 (UNDP 2007). Ironically, since the first democratic elections the HDI has fallen quite dramatically [although the Gini coefficient has slightly improved, although it is still the highest in the world!]. And this is despite the economy having grown at over 5% for a while. This is largely because of the dramatic prevalence of HIV/Aids in the country. According to the 2007 UNDP figures, life expectancy is just 47. This is in Africa’s richest country. [If mortality patterns remain unchanged, a child born today in SA has the same chance of surviving to the age of 40 as a child born today in Guinea-Bissau or Cameroon]. In 2006, there were 950 Aids-related deaths per day!!! 11% of the total population are infected, and for the working population the rates are even higher, 1/5 are infected Actuarial Society of South Africa, 200 6). Figures from last year showed that HIV/Aids reduced the South African work force by 10.8% by 2005. Researchers now estimate that the work force will have lost 25% of its workers by 2020 (Management of HIV and Aids in the Workplace Congress 2007). In terms of poverty, 4, 2 million people were living on less than $1 a day in 2005, up from 1,9-million in 1996, two years after the first democratic elections (South African Institute of Race Relations, 2007). Unemployment is dramatically high in South Africa, with 8million South Africans who are unemployed – that is unemployment of just below 40%, by the expanded definition which does not exclude those who have given up trying to find work. Most are not employable due to their lack of skills (2007). Globalisation and Marginalisation in SA South Africa serves as ‘a textbook example of how globalisation plays itself out in the semi-industrialised world’. - let’s unpack this statement a little bit. We have above seen that there has been a constant increase in economic growth in the last decade. Capital has been the primary beneficiary as productivity and the return on investment dramatically improved in that time. The state has been largely constrained by domestic and foreign capital and has made significant concessions at the macroeconomic policy level. The best-known example for this is GEAR, the ANC’s macroeconomic strategy of 1996. GEAR has been heavily criticised by the Left as South Africa’s ‘homegrown structural adjustment programme’ (Bond 2001). Because it recommends reduction of government spending, focusing instead on the private sector as the source of economic growth and poverty alleviation through ‘trickle-down’. Redistribution was now seen as a by-product of growth. It is easy to imagine that with the levels of poverty and inequality inherited, this can at best be a contested strategy. Labour has been the principal loser in this process. Large numbers of organised workers have been retrenched, casualised and/or forced into the informal economy leading to a further expansion of the underclasses. [of course some workers have done well. Senior managers and certain categories of skilled workers (including professionals) have experienced rising incomes, but they constitute a tiny proportion] The ANC government has been a vocal proponent of the view that integration into the global economy offers developing countries opportunities to develop and to grow rapidly. What has happened though is that labour intensive industries such as clothing, textiles and footwear have shrunk dramatically as the domestic market was lost to imports and local industries struggled to find markets abroad. Mining which dominates South Africa’s economy [platinum and gold] is characterised by capital-intensive industries, so creating stable employment s a big challenge. There was also considerable restructuring in those industries so that since the end of Apartheid, over 200,000 jobs have been shedded (Statistics South Africa 2002). Closer integration in the global economy has resulted in a shift away from manufacturing toward a service-based economy, and the consequent growth in part-time and subcontracted labour processes. Where employment has grown, this has largely been in low-paid and insecure jobs in the informal economy, which is now estimated to constitute some 25 to 30 percent of all employment in South Africa. One distinctive feature of the South African case is that the globalisation process was simultaneously accompanied by a political transition from apartheid to a democratic order. Some people argue that the substantive compromise of this transition was the incoming regime’s support for neo-liberal economic policies in exchange for capital’s acceptance of black economic empowerment and some affirmative action. So skilled black personnel have benefited enormously as the corporate sector has scrambled to meet equity targets in their managerial and staffing structures. but it is also the black majority that has been the victims of neoliberal globalisation. So there is overlap of race and class categories bequeathed by Apartheid which continues to dominate with globalisation and democratisation. This set of processes is catastrophic when combined with a cost-recovery model for the provision of social services. National government has devolved responsibility for the delivery of many services to local government without offering significant increases in their budgets. The only way local governments can provide these services, therefore, is to ensure that they ‘pay for themselves’. In the extreme form, services are privatised, resulting – it is feared – not only in further job losses but in even more determined efforts to extract profit making revenue from residents. Yet with dramatic increases in unemployment, residents find themselves simply unable to pay for water, electricity, rents, rates, and mortgages. Together, as Ballard et al argue ‘these forces amount to a ‘pincer movement’ on the poor, with the state insisting that people pay for their services, housing and land while simultaneously eroding livelihoods’ (2006). Protest in Post-Apartheid The time immediately after the first democratic elections in 1994 was characterised by consensual nation-building, with the various sectors in society pulling in one direction to tackle the problems and developmental challenges that over 40 years of Apartheid (and centuries of colonialism preceding that) had left the new South Africa with. As happens quite often in newly liberated countries, the euphoria of the political transition led many to expect that the need for adversarial social struggle with the state was over. For a while after 1994 this expectation largely informed civil society activity and stifled social struggles. This is also linked to the fact that many of the former civil society leaders were now working in high positions in the public sector. Fast forward over a decade, and South Africa has more protest actions than anywhere else in the world. 7,000 according to Patrick Bond in the last year, although other commentators have contested that figure. During my time in the field, barely a day went by when the media did not report on community protesters and their clashes with the police– and it is not as though these issues were always reported. In fact the government makes considerable efforts to downplay these protest actions and to marginalise protester as ‘Ultra-Left’ or ‘the poor’ Such protest actions comprise a whole array of issues and constituencies, as we will see in a moment. They also vary in scale, organisational form, reach and so on. They are often referred to as ‘new social movements’, but because of these vast differences, what I will try to do today therefore is to synthesise some general points about community movements in SA, give you an overview of social movement theory [which is of course applicable to the study of social movements everywhere] and then discuss one or two specific movements as case studie s. At the end, we may have time to discuss whether or not you think ‘new social movements’ is an appropriate descriptions for these South African civil society organisations. Why have these struggles emerged? Ballard et al identify three types of social struggle emerging with the second democratic election and Thabo Mbeki’s presidency (1999): 1. those directed against a particular government policy (such as COSATU’s opposition to GEAR); 2. secondly, those focusing on government’s partial failure in service delivery (such as the TAC) and 3. those challenging the enforcement of specific government policies and to struggle against government repression (such as the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee or the CCG). continued A number of events can be identified as crucial in contributing to the growth in social action. As is probably obvious from the social and economic indicators I showed you right in the beginning, very broadly speaking, they are a reaction to the huge [and indeed rising!] levels of poverty and inequality in post-Apartheid South Africa.. More specifically, I’ll highlight a number of crucial developments: GEAR had led to a sharp increase in unemployment, rising inequality as well as the commercialisation of basic services, water and electricity shortages and cut-offs. The Anti-Privatisation Forum e.g. developed out of a committee opposing the corporatisation and privatisation of jobs in the Jo’burg city council, and grew into a mass movement that protested water and electricity cut-offs. Likewise, the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee was born out of protest against mass electricity cut-offs. In reaction to the mobilisations around the WCAR [the World Conference against Racism] and the WSSD [the World Summit on Sustainable Development] in Johannesburg in 2002, the Government increasingly started to ban gatherings and repress these movements though a variety of police actions. [The WCAR mobilisations were in fact of crucial importance because they served to unify previously highly localised community struggle into collective, national action] A ‘second wave’ of new social movements came into existence in 2004 with mass uprisings against poor service delivery and corruption in councils. There was an explosion of Crisis committees and Concerned Residents committees everywhere in the country. Desai quote on social movements The following is a quote from Ashwin Desai who is what you could call a scholar-activist; he has been a community activist in Durban for many years but also teaches at the Centre for Civil Society. His book on the emergence on community struggles in Durban townships against the privatisation of water and electricity manages to do what I think a good ethnography should do, namely illuminating large processes of globalisation and marginalisation through describing very local issues… The state's inability or unwillingness to be a provider of public services and the guarantor of the conditions of collective consumption has been a spark for a plethora of community movements (…) The general nature of the neo-liberal emergency concentrates and aims these demands towards the state (…) Activity has been motivated by social actors spawned by the new conditions of accumulation that lie outside of the ambit of the trade union movement and its style of organising. What distinguishes these community movements from political parties, pressure groups and NGOs is mass mobilisation as the prime source of social sanction’ Ashwin Desai (2002) ‘We are the Poors’ So if we unpack a bit what he says, then on the one hand he points towards some of the processes that we have already discussed as contributing to the rise of these SMs, e.g. neoliberalism. The ‘neo-liberal emergency’ clearly is not a local or national issue alone; it is tied in with processes of globalisation. But he also mentions the state as the focus point for demands and protest actions. So this points towards the national level. And in the last sentence, he identifies one characteristic of social movements, at least in the SA context: they have ‘mass mobilisation as the prime source of social sanction’. I will talk a bit about social movement theory now to see how we may understand the existence of movements like the ones Desai is describing. SMT Here are three different, but quite complementary definitions of social move,ments, the last of which is specifically referring to SA movements. ‘The proper analogy to a social movement is neither a party nor a union but a political campaign. What we call a social movement actually consists in a series of demands or challenges to power-holders in the name of a social category that lacks an established political position’ (Tilly 1985) ‘Forms of collective action with a high degree of popular participation, which use noninstitutional channels, and which formulate their demands while simultaneously finding forms of action to express them, thus establishing themselves as collective subjects, that is, as a group or social category’ (Jelin 1992) Ballard et al, writing on South African movements in particular, put it rather differerently, pointing out that ‘social movements are thus, in our view, politically and/or socially directed collectives, often involving multiple organisations and networks, focused on changing one or more elements of the social, political and economic system within which they are located’. Social movement theories Investigations of social movements commonly build upon three central aspects relevant to our understanding of mobilisation: 1. the structure of opportunities and constraints within which movements may or may not develop These serve to highlight the opportunities for action and suggesting the possible forms that movements will take as they respond to the context in which they organise. Opportunity structures cannot, however, explain the rise of new movements on their own. 2. the networks, structures and other resources which actors employ to mobilise supporters and what access they have to political and material resources. These approaches can highlight how movements emerge, although not necessarily how 3. the ways in which movement participants define or frame their movement. These approaches are based upon identity-oriented paradigms which stress the importance of social relationships for any understanding of movement activity; they bring cultural frames including shared meanings, symbols and discourses into the analysis. These aspects can be applied to old” and “new” social movements, bringing together movements for liberation, independence and freedom which often sought revolutionary change and the overthrow of the state with the “self-limiting radicalism” of “new” social movements which demanded greater equality and rights without challenging the structure of the formally democratic state and the market economy. But they can also be used to understand the so-called ‘new-new’ transnational movements which press for alternative globalisations and in so doing challenge powerful transnational and global political and economic structures (e.g. the anti-globalisation movement). Summary: Social movements in South Africa So just to tie together what we have looked at in terms of South Africa’s socio-economic conditions, as well as some social movement theory, there are a number of arguments we can sum up regarding SMs in South Africa (taken from Ballard, Habib et al.) Their emergence is linked to processes of globalisation. Namely: High levels of poverty and inequality have given rise to such movements, which are related to economic restructuring resulting in mass unemployment as well as a cost-recovery model in service provision. 1. identity issues exist within movements largely concerned with distributional issues in that they exacerbate material disadvantage [=absence of middle-class individuals, which are the kind of people that make up ‘new-new’ SMs in Western world --- see the article that was your key reading] 2. rather than being spontaneous grassroots uprisings, social movements depend on a number of material resources and networks of solidarity and personal histories 3. contemporary movements are a product of the post-Apartheid political environment, so that a number of legal strategies ins drawn upon and media and democratic institutions are engaged by some. This stands in direct contrast with what is by many perceived as an increasingly authoritarian state which aims to repress popular protest. 4. diversity of relations between movements and the state, ranging from engagement to adversarial. ‘repertoire of tactics’ (17) used by successful movements. expand on this point… so SM landscape very plural and complex. It raises many questions about how we are to imagine political contestation, progressive politics or even socialism. What vision of a society is apparent here? And who is central to this vision? Can it still be the working classes of classical Marxist theory in a context of 40% unemployment? How does race fit into this? This is the theoretical part of the lecture over, any questions so far??? Case studies 1. Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign The Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign is a popular movement made up of poor and oppressed communities in Cape Town, South Africa. It was formed on November 2000 with the aim of fighting evictions, water cut-offs and poor health services, obtaining free electricity, securing decent housing, and opposing police brutality. The movement is the oldest of the first generation of so-called 'new social movements' to spring up after the end of apartheid and is known for its direct action style militancy, its refusal of NGO authoritarianism[1] and its networked or hydra style mode of organization. It has an alliance with the KwaZulu-Natal shack dweller's movement Abahlali baseMjondolo and the two organizations support each other closely. The AEC is currently an umbrella body for community organizations, crisis committees, and concerned residents movements who have come together to organise and demand their rights to basic services. anti-government, anti-NGO, does not support the social movement Indaba But since its inception the SMI has degenerated into a vehicle controlled by NGOs. Now it merely poses as a forum for bringing together social movements. In reality the SMI has become an obstacle to the linking up of real social movements around the country and is a source of division. The Western Cape Anti Eviction Campaign will not allow some NGO's and academics to further their careers with the blood, sweat and tears of communities. We despise the way they act as Trojan horses and the way they co-opt activists because of the resources they enjoy. Major social movements such as Abahlali base Mjondolo in Natal and the WCAEC withdrew from the SMI a year ago because it no longer fulfilled its original function. The SMI needs to be reclaimed and driven by people on the ground and not by its\ self-appointed 'leaders'. Anti-Privatization Forum The formation of the APF was the result of co-operation by three broad but not homogeneous groupings of the left. First there were left activists within the ANC/SACP/COSATU alliance who felt a sense of frustration, particularly after the adoption of GEAR by the ruling party. However, in most cases this did not translate into a challenge of the increasingly hegemonic political and economic positions of the ruling party. Indeed, where there was an attempt to do this, such as in ANC councillor Trevor Ngwane’s criticism of the cost-recovery model in local government (Ngwane, 2003), or the SACP’s Dale McKinley’s criticism of the leadership, such expression of dissent was dealt with ruthlessly. At the same time, many left activists outside the Alliance, mostly young, were also searching for relevance, particularly in light of developments in the anti-globalisation movement elsewhere in the world. Many of these were student or youth activists while others worked in various non-governmental organisations. Some belonged to remnants of socialist groups such as the Marxist Workers’ Tendency which had faded out of the political scene following the 1994 elections. Some in this group had direct or electronic links with activists in other parts of the world and were able to exchange views about the state of the bourgeoning anti-globalisation movements. The third grouping comprised working class activists drawn from communities that were looking for answers in a context where retrenchments and cost-recovery had combined to destroy their livelihoods and limit their access to basic goods and services. Made up of community organisations and political organisations as affiliates… Questions for discussion So why are we concerned with this? Why is the study of these movements in SA important? Are movements important to a young democracy? Some commentators see the contribution of SMs to democracy as positive: social movements are contributing to the plurality of civil society which is a sign of a mature democracy. Of course other South African stakeholders are less than enthusiastic – the state for instance. What do you think?