Between-Herd Biosecurity Risk Factors

advertisement

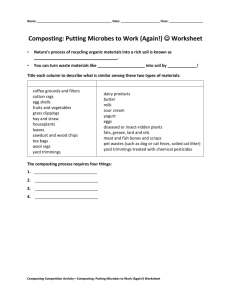

Between-Herd Biosecurity Risk Factors The greatest risks to the health of livestock on your farm are from other animals or their manure. In order of risk, from highest to lowest, are the following situations: Adding new livestock to the farm without a quarantine period. Failing to quarantine new additions for at least two weeks, preferably four weeks. Failing to require testing for specific diseases prior to addition. Failing to require vaccination for specific diseases prior to addition. Allowing livestock to return from fairs, shows, or exhibitions without quarantine. Allowing other animals (domestic or wild) to contact your livestock, feedstuffs, or water sources. Failing to prevent disease transfer via human contact, vehicular traffic, or equipment (including needles and rectal sleeves) used on more than one animal. Isolation and Quarantine Being able to isolate sick animals and quarantine new or returning animals will bolster your entire herd health program and should be a priority for your herd’s biosecurity. An isolation or quarantine area should achieve the following objectives: Provide an air space, water source, and feed source separate from rest of livestock. Prevent direct contact with rest of livestock. Provide a clean, dry, comfortable resting space for the animal(s). Provide transition to new ration. Provide adequate restraint facilities for examinations and administration of treatments. Allow equipment storage in that area—shovels, halters, buckets, etc.— for use only in isolation area. Prevent the movement of equipment and manure from the isolation area to other locations with livestock. 23 Addition of New Animals Pre-purchase process Bringing new animals onto your farm may also bring new diseases. Even buying or borrowing a bull, ram, or buck could compromise the biosecurity of your farm. Review the following checklist before and immediately after new animals are purchased. Organic livestock farms will recognize that careful examination of animals is needed since treatment options are more limited. Ask your veterinarian to contact the veterinarian of the source herd. Test and vaccinate as needed. The key point is to determine the vaccination and health status not just of the individuals you are buying, but also of the herd of origin. Specifically ask about the following conditions: 1. Mastitis (in dairy animals) Culture cows for Strep. ag, Staph. aureus, and Mycoplasma. Conduct a series of three bulk tank or individual cultures plus SCC. Purchase open or bred heifers to minimize the risk of mastitis (but recognize the risk will not be zero). 2. Hoof health Inspect for hairy heel warts (cattle), foot rot, foot scald (small ruminants), and lameness. Isolate and treat any problems upon arrival. 3. Vaccination status Ask for records of initial vaccination series and boosters for respiratory diseases, leptospirosis, bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) in cattle, clostridial diseases (CD Tet in small ruminants), and rabies. Booster or initiate a vaccination series to match your herd vaccination program. Consult with your veterinarian about your routine and purchased-animal vaccination programs. Boost vaccines 3 weeks prior to movement, if appropriate. 4. Herd health status History of abortions. In cattle, diagnoses of neosporosis, leptospirosis, salmonellosis, BVD, lymphoma, or Johne’s Disease. In small ruminants, diagnoses of Johne’s, leptospirosis (Leptospira interrogans), vibrio (Campylobacter fetus), chlamydia (Chlamydia psittaci), toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii), or listeriosis (Listeria monocytogenes). Breeding soundness exam prior to purchasing male breeding stock. 24 Test results negative for persistent infection (PI) with BVD in cattle. Serologic status for bovine leukosis virus (BLV) in cattle, Johne’s Disease (JD or MAP) in cattle and small ruminants; caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE) in goats; ovine progressive pneumonia (OPP) in sheep and goats. 5. Deworming/antiparasitic program Check fecal; conduct egg count and test anthelmintic resistance in small ruminants. Get history of past deworming practices. Check for signs of lice, mange, ringworm, and warts. Use pour-on or other insecticide upon arrival, if indicated. Post-purchase management of animals The ability of tests to find the presence of a disease (sensitivity) is limited, so testing alone does not eliminate the risks inherent to purchasing animals. Therefore, post-purchase management of incoming animals as well as management of the home herd are important control points. Identify new arrivals and segregate for at least 2-3 weeks. Use separate housing, feeding, and birthing areas (ideal). Use separate housing and feeding areas (acceptable). Prevent contact with other livestock (minimum acceptable). Do not use an “old” barn that could compromise stall comfort, air quality, or feed management as an isolation facility. Booster vaccines, if necessary. Minimize stress. Provide clean, comfortable housing with good ventilation. Consult nutritionist to develop transition ration. Change to new ration slowly. Inspect and treat feet for warts, scald, or lameness. Prevent manure from moving from the isolation area to the rest of the herd. Milk new and isolated dairy animals last. Observe and examine frequently for early disease detection. Plan and prepare in advance. Monitor aggressively. Early recognition is crucial to preventing spread of disease. Identify and train staff who will monitor health. Create written protocols for monitoring and treatment with criteria such as fever, signs of infection, lameness, or off-feed. 25 Addition of New Animals Animal importation Anyone who has brought an animal into Vermont knows that they must meet certain regulatory requirements. These restrictions are designed to prevent the introduction of diseases that are not currently present in the state. Although the restrictions vary by species, there are some similarities in the process. Since some diseases can spread from one species of animal to another—or even to humans—it is critical that all animal importers follow the applicable restrictions. The importation of monkey pox into the United States in 2003 with African rats is an example of what can happen if adequate safeguards are not followed to ensure the health of the animals entering this country. The United States is free of many diseases that occur in other parts of the world. Foot and Mouth Disease is a well-known example. Inspection of imported animals and feedstuffs plays a critical role in preventing the introduction of such diseases. Control programs are in place for a number of diseases that have been nearly eradicated from the United States, including brucellosis and tuberculosis. These still exist in geographic regions where wildlife (bison and deer, respectively) serve as a reservoir for disease and periodically infect livestock. As of July 2003, Vermont is free of brucellosis, bovine tuberculosis, and pseudorabies. These and other diseases are reportable if diagnosed (or suspected) in animals in the state. All imported animals must be accompanied by the following three items: Import permit Certificate of veterinary inspection within 30 days of importation Official individual identification. Any required testing must be done in the state or country of origin. The main disease concerns associated with various species are listed on the next page. Additional information on regulations pertaining to the importation of animals is available through the Vermont Agency of Agriculture and USDA APHIS websites. The State Veterinarian will have the latest information on rules and regulations. 26 Regulated diseases The entry of animals from other parts of the country into Vermont is regulated to prevent the introduction of diseases found elsewhere in the United States. The regulated diseases are listed below by species, but you will notice several diseases affect more than one species. Vesicular Stomatitis is a particular concern because the signs resemble those of Foot and Mouth Disease. An animal with a vesicular disease will be quarantined and other restrictions may apply until a specific diagnosis is confirmed. Cattle/Bison Brucellosis Tuberculosis Anaplasmosis Bluetongue Psoroptic mange Vesicular Stomatitis Deer/Elk/Other cervidae Brucellosis Tuberculosis Epizootic hemorrhagic disease Anaplasmosis Elaphostrongylinae nematode (worm) Chronic wasting disease in elk Bluetongue Vesicular Stomatitis Camels/Llamas/Alpacas Brucellosis Tuberculosis Bluetongue Vesicular Stomatitis Sheep Bluetongue Psoroptic mange Scrapie (affected or exposed) Vesicular Stomatitis Goats Brucellosis Tuberculosis Caseous lymphadenitis (CLA) Vesicular Stomatitis Pigs Brucellosis Pseudorabies Vesicular Stomatitis Horses Equine infectious anemia (Coggins) Vesicular Stomatitis Poultry Pullorum-typhoid Avian influenza Other species not included in this list may also have specific regulations. If you are importing an animal that is not on this list, contact the State Veterinarian to determine which agency has regulatory authority and follow the proper procedures. 27 Livestock Exhibitions Exhibitor’s checklist Contact the fair superintendent to find out what tests your animal must pass before attending the fair. Have your animal’s health certificate and test results ready for inspection before checking in. Use your own truck or trailer to haul your animals, or, if that is not possible, make sure that the equipment used to haul your animals is clean and recently disinfected. Once you are at the fair, be sure your animals have access to clean water and feed in containers you provide. Milk your dairy animals with your own equipment. Avoid sharing of grooming equipment and feed and water containers. Disinfect any shared equipment before it is used again at home. Minimize nose-to-nose contact with other animals to the extent that it is possible. Keep your animals as comfortable as you can to help reduce stress. Discourage fair visitors from petting or feeding your animals. Signs can be posted asking visitors not to touch or feed the animals. Practice good personal hygiene. Wash with soap and water after handling your animals and put on clean clothes. Keep your boots and shoes clean. Make sure you don’t track barn muck into your house. Isolate all purchased animals and animals returning from a fair for a minimum of two weeks, but preferably for 30 days. Ideally, this would be in a completely separate place to avoid contact or airborne transmission of disease. If this is not possible, it should be a separate pen in a different building or at least a separate corner of the barn. (See Isolation and Quarantine on page 23.) 28 Superintendent’s checklist Conduct a meeting with all exhibitors before the fair to review biosecurity procedures and checklists. Examine all health certificates for veterinary inspection and appropriate tests. A list of species specific animal health requirements can be requested from the State Veterinarian or found online at www.vermontagriculture.com/healthstd.PDF. Ensure that a veterinarian will be on hand to inspect all arriving animals for symptoms of ill health. Ensure that a veterinarian regularly inspects animals and is available to examine livestock that become ill during the exhibition. Make sure equipment from farms has been cleaned and disinfected. Provide clean and properly disinfected animal housing facilities. Provide housing with adequate space and proper ventilation. Provide access to clean water. Provide storage areas for manure and waste bedding away from animal housing and public traffic areas. Lime manure pile daily to prevent ammonia volatilization. Conduct daily walk-through inspection with the fair veterinarian. Keep a log of animals with health issues and report them to the fair veterinarian. Keep a log of unusual interactions between visitors and animals. International travelers should be discouraged from visiting livestock barns. If international travelers are to be given access to livestock barns, they should have already been in US for a minimum of five days and have been cleared by the fair livestock superintendent. (See Foreign Animal Disease Prevention on page 45.) 29 Superintendent’s checklist (continued) Conduct daily exhibitor meetings to discuss biosecurity issues and interactions with visitors. Provide hand-washing stations convenient to animal exhibition areas. Signs should be present to make these areas obvious, along with a suggestion to wash hands after petting animals. Portable Atomizing Wash Stations are available from Best Sanitizers, 888-225-3267. (On their website, http://www.bestsanitizers.com/, click on the fair page link.) Display “Wash your hands before eating” signs. Make sure each exhibitor leaves with a biosecurity checklist. Provide exhibitors with written health requirements in advance of the animal exhibition. Request that exhibitors not bring unthrifty animals, even if they are part of an organized project. Establish health requirements that meet or exceed all local, state, and national animal exhibition requirements. 30 Disposal of Dead Animals Carcasses can be a hazard to the environment and other animals so they require special handling. To minimize soil or water contamination and the risk of spreading disease, guidelines for proper carcass disposal must be followed. Disposal options include calling a licensed collector to remove deadstock or burial in an approved Animal Disposal Pit. Alternatives include incineration and composting. Composting avoids the air contamination associated with burning mortalities and is economical. Since the heat in the pile eliminates most pathogens, composting can also improve the biosecurity of your farming operation. If death was caused by a highly infectious disease, Clean and disinfect the area after the carcass is removed. Wear protective clothing when handling deadstock and thoroughly disinfect or dispose of clothing before handling live animals. Properly dispose of contaminated bedding, milk, manure, or feed. Check with your State Veterinarian about disposal options. Burial may not be legal. Special methods of incineration or composting may be used in cases of highly infectious diseases. If a licensed collector picks up your deadstock, Limit the access of the deadstock collector and his vehicle to areas well away from other animals, their feed and water supply, grazing areas, or walkways. If you bury deadstock on your own property, minimum site requirements in Vermont, according to the Agency of Natural Resources Procedure Addressing Disposal of Dead Animals (2001), are: 6 feet above bedrock, 4 feet above seasonal high ground water 2 feet of soil on top, final cover greater than 100 feet from property lines greater than 300 feet from water supplies Animals that were exhibiting neurologic signs prior to death will need to have samples collected by your veterinarian for testing. Special disposal regulations may apply. 31 Composting deadstock If you compost your deadstock, follow the steps listed below: 1. Decide what method you will use. Composting methods include static piles, turned windrows, turned bins, and contained systems. Information on the first three methods is available on several websites listed on page 34. Static piles with minimum dimensions of 4 feet long, by 4 feet wide, by 4 feet deep are by far the simplest to use. Turned windrows may be an option for farmers already composting manure in windrows. Turned bin systems are more common for handling swine and poultry mortalities. The eco-pod is a contained system developed by Ag-Bag, which has been used to compost swine and poultry mortalities. (Information is available through Ag-Bag, 800-334-7432 or compost@ag-bag.com.) 2. Select an appropriate site. Well-drained with all-season accessibility. At least 3 feet above seasonal high ground water levels. At least 100 (preferably 200) feet from surface waterways, sinkholes, seasonal seeps, or ponds. At least 150 feet from roads or property lines--think about which way the wind blows. Outside any Class I groundwater, wetland or buffer, or Source Protection Area – contact NRCS for verification. 3. Select and use effective carbon sources. Use materials such as wood chips, wood shavings, coarse sawdust, chopped straw or dry heavily bedded horse or heifer manure as bulking materials. Co-compost materials for the base and cover must allow air to enter the pile. If the bulking materials are not very absorbent, cover them with a 6inch layer of sawdust to prevent fluids from leaching from the pile. Cover the carcass 2 feet deep with high-carbon materials such as old silage, dry bedding (other than paper), sawdust, or compost from an old pile. Plan on a 12’ x 12’ base for an adult dairy or beef animal. The base should be at least 2 feet deep and should allow 2 feet on all sides around the carcass. When composting smaller carcasses, place them in layers separated by 2 feet of material. 32 4. Prepare the carcass. After placing the carcass on the base, lance the rumen of adult cattle. Forget this once and you’ll never forget again! Explosive release of gasses may uncover the pile releasing odors and attracting scavengers. 5. Protect the site from scavengers. Adequate depth of materials on top of the carcass should minimize odors and the risk of scavengers disturbing the pile. Scavengers may be deterred by the temperatures within the pile, but, if not, an inexpensive fence of upside down hog wire may be adequate to avoid problems. 6. Monitor the process. Keep a log of temperature, carcass weight, and co-compost materials when each pile is started. Weather and starting materials will affect the process. Measure pile temperature with a compost thermometer 6 to 8 inches from the top of the pile and deep within to check for proper heating. Check daily for the first week or two. Pile temperature should reach 131oF for 3 consecutive days to eliminate common pathogens. Record events or problems such as scavenging, odors, or liquid leaking from the pile. Wait. Most large carcasses will be fully degraded within 4-6 months. Smaller carcasses take less time. Turning the pile after 3 months can accelerate the process. 7. Use the finished materials carefully. Use as the base for a new pile. Bones add structure and will continue to decompose. Spread on fields growing animal feedstuffs. Avoid spreading material with large bones on fields as they may fragment and puncture tires. Do not spread skulls. They’re bad for public relations! 33 Resources on deadstock disposal Procedure Addressing Disposal of Dead Animals, Solid Waste Management Division, Department of Environmental Conservation, State of Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, 802-241-3888. Natural Rendering Fact Sheet 2002, Cornell Waste Management Institute, available at http://www.cfe.cornell.edu/wmi/Composting.html or through the Natural Resource, Agriculture, and Engineering Service (NRAES), 607-2557654. Natural Rendering Video. Cornell Waste Management Institute. NRAES #163. This video describes mortality and butcher residual composting featuring eight operations. Available through NRAES, 607-255-7654. Farm Based Composting: Manure and More Video, NRAES #150. Video highlights 14 farm operations and six different composting technologies. Available through NRAES, 607-255-7654. Field Guide to On-Farm Composting, NRAES #114. Guide provides practical information applicable to manure and mortality composting. Available through NRAES, 607-255-7654. Minnesota Department of Agriculture, http://www.mda.state.mn.us/composting/default.htm. Provides basic information on methods. Also describes legalities of composting mortalities in Minnesota. Natural Rendering website. Penn State College of Agricultural Sciences. http://composting.cas.psu.edu/NatRendering.htm. Provides links to resources and shows pictures of the mortality composting process. 34 35