Humans and Climate Rapidly Changing Global Land Cover

Katrina Outland, Science Journalist

Marine Biology and Writing, Hawaii Pacific University

outland@jyi.org

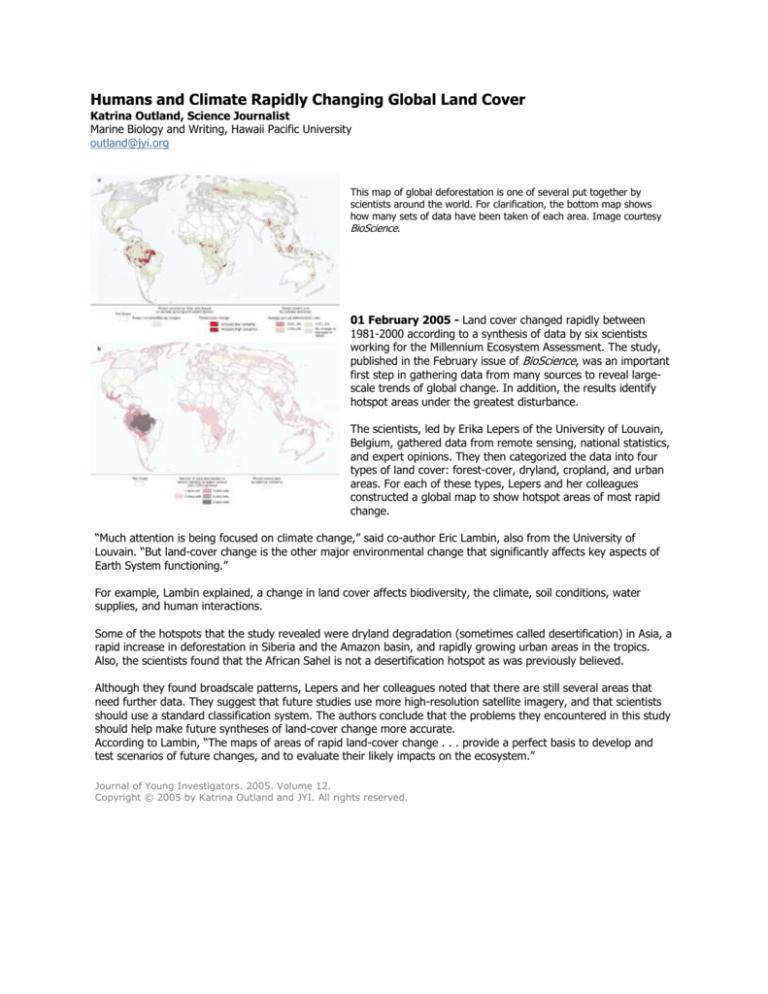

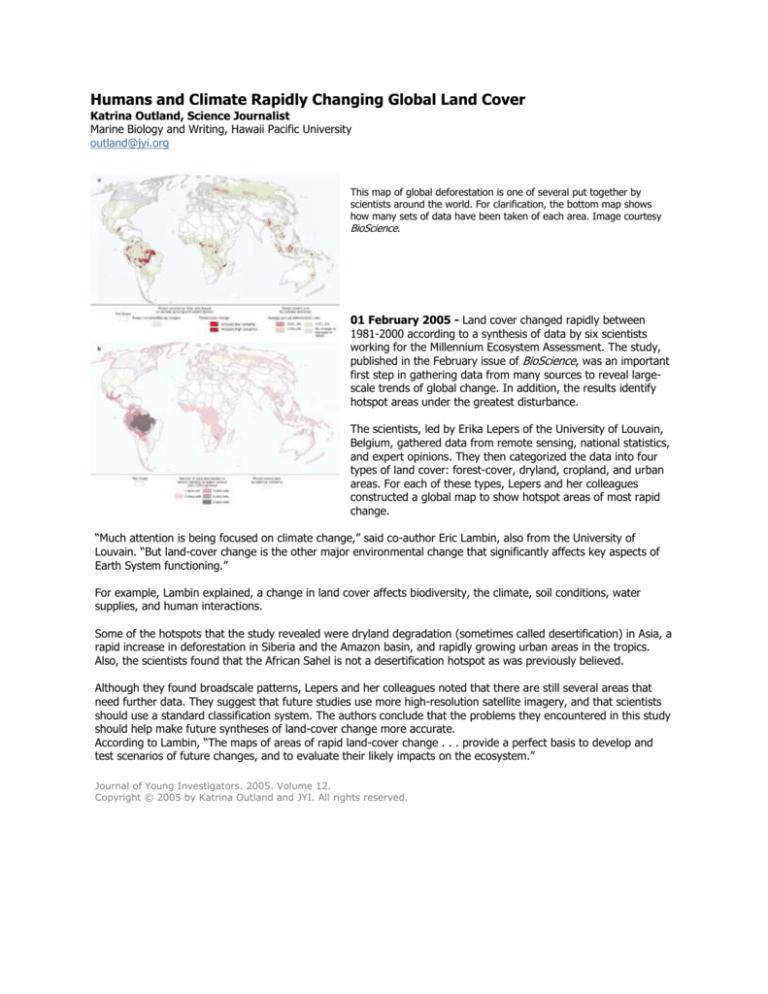

This map of global deforestation is one of several put together by

scientists around the world. For clarification, the bottom map shows

how many sets of data have been taken of each area. Image courtesy

BioScience.

01 February 2005 - Land cover changed rapidly between

1981-2000 according to a synthesis of data by six scientists

working for the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. The study,

published in the February issue of BioScience, was an important

first step in gathering data from many sources to reveal largescale trends of global change. In addition, the results identify

hotspot areas under the greatest disturbance.

The scientists, led by Erika Lepers of the University of Louvain,

Belgium, gathered data from remote sensing, national statistics,

and expert opinions. They then categorized the data into four

types of land cover: forest-cover, dryland, cropland, and urban

areas. For each of these types, Lepers and her colleagues

constructed a global map to show hotspot areas of most rapid

change.

“Much attention is being focused on climate change,” said co-author Eric Lambin, also from the University of

Louvain. “But land-cover change is the other major environmental change that significantly affects key aspects of

Earth System functioning.”

For example, Lambin explained, a change in land cover affects biodiversity, the climate, soil conditions, water

supplies, and human interactions.

Some of the hotspots that the study revealed were dryland degradation (sometimes called desertification) in Asia, a

rapid increase in deforestation in Siberia and the Amazon basin, and rapidly growing urban areas in the tropics.

Also, the scientists found that the African Sahel is not a desertification hotspot as was previously believed.

Although they found broadscale patterns, Lepers and her colleagues noted that there are still several areas that

need further data. They suggest that future studies use more high-resolution satellite imagery, and that scientists

should use a standard classification system. The authors conclude that the problems they encountered in this study

should help make future syntheses of land-cover change more accurate.

According to Lambin, “The maps of areas of rapid land-cover change . . . provide a perfect basis to develop and

test scenarios of future changes, and to evaluate their likely impacts on the ecosystem.”

Journal of Young Investigators. 2005. Volume 12.

Copyright © 2005 by Katrina Outland and JYI. All rights reserved.