A Good Example of a Student`s Paper

advertisement

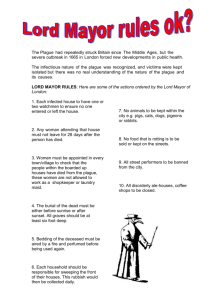

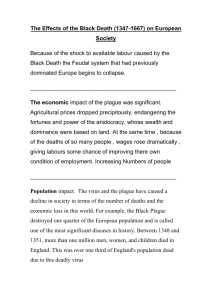

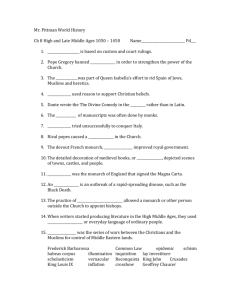

A Good Example of a Student's Paper Scenario 2 Susan Rindlaub 1) It is difficult to know the exact location of the plague hearth in general because the plague’s origin is still a mystery. Many scholars argue that the plague’s original hearth was China and that the disease spread to Europe along trade routes. Others contend that the plague originated in East Africa. In terms of the plague in London, St. Botolph, which was often the first parish to have increased death rates, was likely the hearth for several different years of plague outbreak. During the Great Plague of London in 1665, the hearth was likely St. Giles-inthe-fields, where the first cases were discovered in April of 1665. 2) An example of relocation diffusion is the plague moving from China along trade routes towards European cities such as London. Another example of relocation diffusion was during the Great Plague of London, when the outbreak likely originated in St. Giles, just west of the walled city, but later, the disease occurred in villages far away, such as the Derbyshire village of Eyam. Contiguous diffusion occurred often during outbreaks in London. The plague tended to originate in outer North parishes such as St. Boltoph, and then spread in a progressive pattern from one parish to a neighboring one, towards the inner city. A specific example of this is the disease spreading from St. Olave Hart Street parish to the nearby St. Peter Cornhill Parish. Hierarchical diffusion also occurred, as the plague most often began in poor, crowded parishes with few substantial households before it spread to wealthy parishes that lay in the inner part of the city. 3) During the many plague outbreaks in London between 1593 and 1665, the disease almost always experienced some distance decay. During the epidemics of 1593, 1603, 1625, and 1655, the effects of the disease were much more severe in the poor outer parishes than in the inner ones. Following the pattern of distance decay, during these years, the plague’s hearth was in outer parishes such as St. Botolph, which had high mortality rates, and then spread progressively towards the inner city, with less severe effects and lower death rates as the disease moved farther from the hearth. 4) The main cultural barriers to plague diffusion were the result of class differences. During the years of plague in London, the disease usually originated in poor, crowded outer parishes, where garbage and filth existed as a perfect breeding ground for rats that spread the plague. Before the disease could fully spread towards the wealthier inner parishes, many of the rich simply fled the city, along with doctors and clergy. While the rich had the option to physically leave the city, the poor were not allowed to leave, and thus experienced the highest levels of death. Essentially, upper class people were less likely to experience plague because they had the ability to leave the area of an outbreak. 5) The main physical barriers to diffusion were the physical walls and boundaries set up to contain the plague. Some countries established large “pest houses,” where those afflicted with plague were quarantined. In London, people were forced to stay inside their homes and their doors were physically nailed shut so they could not leave. Tragically, the walls of people’s own houses often represented the greatest physical barrier. In enforcing plague order, “watchers” or guards presented another barrier, as they patrolled the streets to make sure the sick did not escape. There were also guards at boundaries around London who enforced rules that the poor, seen as carriers, could not leave the area. 6) The plague had severe impacts on the environment, especially as the mortality rate increased. Because of the huge number of deaths that occurred during summer months, proper burials were not possible, and many sick were left to die and rot inside their homes and in the streets. Other victims were gathered up by scavengers and rakers, who simply tossed the dead into huge pits. The amount of human waste and filth in general also increased in London, as the city could not deal with the sewage and mounting dead bodies. Thousands of dogs and cats were also killed (as they were assumed to be carriers of the Plague), which increased the population of rats that no longer had predators. 7) It is debatable whether the bubonic plague, alone, was responsible for all of the deaths during the plague years. However, I will explain mortality in general terms, which might take into account several different plagues. In terms of population figures, around 100,000 people alone died in London during the Great Plague of 1665. The plague truly had a drastic negative affect on the population, and not just because of deaths, but also as a result of so many rich fleeing the city. The plague also had significant effects on the economy, as many markets closed, and street stalls were banned. Inns and lodging houses were also closed, and trade was strongly discouraged for fear of spreading the disease. Many outlying villages and poor areas were simply cut off from contact and trade. However, there were some people who benefited, as a new plague economy sprang up. Apothecaries had increased business and sold a lot of potions and medicine, and many women were employed for the first time as nurses, while men worked as guards, scavengers, or rakers. The cultural effects are more difficult to define, but it is clear that the plague left a huge sense of fear throughout London, but also an increased sense of community and shared bonding among survivors. Many survivors’ religious faith was strengthened as they felt their survival was due to God’s hand. The status of woman was raised slightly, as they were able to work as nurses. Unfortunately, the gap between rich and poor was even more defined by the plague as the poor suffered the greatest losses.